![]()

CHAPTER

1 Social Justice, Equity, and Mathematics Education

With every single thing about math that I learned came something else. Sometimes I learned more of other things instead of math. I learned to think of fairness, injustices, and so forth everywhere I see numbers distorted in the world. Now my mind is opened to so many new things. I’m more independent and aware. I have learned to be strong in every way you can think of. (Lupe, 8th grade, May 1999)1

On Wednesday, September 11, 2002, the first anniversary of the World Trade Center attack, I stood in front of my seventh-grade mathematics class at Rivera Elementary (a pseudonym), a Chicago public school located in a Mexican immigrant community. At noon, the assistant principal’s voice came over the loudspeaker announcing the time, and the city shut down for three minutes of silence by order of Chicago Mayor Daley. At 12:03 I looked up at the 30 somber students in front of me and asked them to put away their math books. I went to the overhead projector, put a blank transparency on the machine, and sat facing them on my high stool. After a few more seconds of silence, I asked my class, “What questions do you have about September 11?”

This was our third class together, and we had just begun to build real relationships. Given the solemnity of the moment and subject, it was not surprising that students were initially silent. But the questions began to come, slowly at first, and then they came and came. I made no attempt to create discussion or answer their questions but only wrote them on the overhead. Their responses were from the heart, reflecting seventh-graders’ fears, lack of knowledge about the situation, and plain good sense. They asked things like, “Where is Bin Laden?”, “If the U.S. goes to war with Iraq, who will be the allies?”, “Will/Can there be another world war?”, and “Why did they choose the U.S.?” Candela asked, “Why does Mr. Rico (my classroom name2) want to know our questions?” That question I did answer—I told them that I wanted to know them better and that I wanted them to ask as many questions as possible.

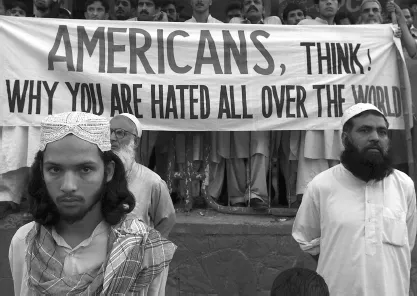

After about 15 minutes as the questions slowed, I asked students what questions they thought that people in other countries asked about September 11. They had fewer replies to this, and after about five minutes, I put on the overhead a photo of a rally held in Islamabad, Pakistan on September 15, 2001. The photo showed several men holding a large banner that read, “Americans, Think! Why You Are Hated All Over the World?” (See Figure 1.1.) I asked students what the photo meant to them. They answered things like “people hate us because we are free,” “because of our money,” and finally someone said, “because we stick our noses in so many other countries’ business.”

Figure 1.1 Islamabad, Pakistan, demonstration, September 15, 2001 © AP/Wide World Photos.

During this conversation, someone mentioned bombing Afghanistan. I told students that none of the hijackers were thought to be Afghan. I then shared some history, available to anyone who digs, reads, and remembers, but not widely propagated in mainstream media—the CIA involvement in Afghanistan and its funding of the Taliban and the mujahedeen (anti-Soviet resistance3) in the amount of well over $4 billion (Galster, 2001). I also told them that then-President Reagan referred to the mujahedeen (including Bin Laden) in 1985 as “freedom fighters” (Ahmad, 2001). Someone made a comment about our tax dollars funding them.

After about 40 minutes, we returned to doing mathematics (we had a double period that day). As students worked on problems, I circulated among them. Moises asked me if I would fight against Iraq or Afghanistan. I told him that I would not because I did not believe in going to war for oil, power, and control. Then Lucia said her brother was in the Navy. I asked why, and she said because he did not know what else to do. I then asked would he have enlisted if he had received a four-year college scholarship with full room and board, books, and fees. She said no.

That Friday, I gave my students the first of what I call real-world mathematics projects, titled “The Cost of the B-2 Bomber—Where Do Our Tax Dollars Go?” (see Appendix 1). The essence of the project was to use U.S. Department of Defense data and find the cost for one B-2 bomber, then compare it to a four-year, full scholarship to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a prestigious out-of-state university. The students had to answer whether the whole graduating class of the neighborhood high school (about 250 students) could receive the four-year, full scholarships for the cost of one bomber. Eventually, they discovered that the cost of one bomber could pay for the full, four-year scholarships for the whole graduating class (assuming constant size and costs) for the next 79 years!

This real-world project was one of many that I gave my students in five different classes at Rivera from 1997 to 2003. These projects formed a core component of what I call teaching mathematics for social justice, the subject of this book. Hopefully, this vignette gives a taste of what my classes were like—in which real and potentially controversial issues were explored and discussed; genuine views (including my own) and differences were solicited, accepted, and respected; and mathematics became a key analytical tool with which to investigate, make sense out of, and possibly take action on important social justice issues in the world. As Leandro pointed out on the B-2 bomber project, “This is a good way to understand the world because now we see that mathematics is all around us.” The stories of my classes, and my students’ and my voice, and even those of their parents, fill these pages.

Before sharing these stories, I give a brief overview of this book. My central argument is this: Students need to be prepared through their mathematics education to investigate and critique injustice, and to challenge, in words and actions, oppressive structures and acts—that is, to “read and write the world” with mathematics. I discuss the quoted terms in detail, but essentially to read the world is to understand the sociopolitical, cultural-historical conditions of one’s life, community, society, and world; and to write the world is to effect change in it. I contend that mathematics education can serve the larger struggles for human emancipation that Paulo Freire (1970/1998) wrote about in Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I also argue that teachers (and not only mathematics teachers) need to conceptualize themselves as “transgressive” (hooks, 1994), see their role as part of larger social movements, and explicitly attempt to create conditions for young people to become active participants in changing society. This idea is not new in general, but as I discuss in the next section, with few exceptions it is rarely discussed in mathematics education.

I also describe who my students were, not as individuals (that occurs through their writing), but how they fit into the world as members of particular racial/ethnic, linguistic, and social class groups. In this chapter, I briefly situate their story within the current sociopolitical context of the United States and the world, one of global contradictions and increasing economic and social polarization. I examine the mathematics experiences of those groups and frame my teaching and students’ learning with respect to the goals of mathematics education in the country today. I present the plan of the book and conclude the chapter with an introduction to Rivera Elementary. Along the way, I describe myself and how I understand my roles in this narrative, especially my relation to students and their community.

Sociopolitical Context of Mathematics Education

Mathematics education in the United States today is complex and cannot be fully understood independent of broader forces affecting all areas of education—and society. Apple (2004) succinctly characterized the educational situation:

An unyielding demand—perhaps best represented in George W. Bush’s policies found in No Child Left Behind—for testing, reductive models of accountability, standardization, and strict control over pedagogy and curricula is now the order of the day in schools throughout the country. In urban schools in particular, these policies have been seen as not one alternative, but as the only alternative [emphasis original]. (p. x)

I do not try to fully explain this context, as others have done a far better job than I could (e.g., Apple, 2001; Lipman 2004), but important aspects relate specifically to mathematics education. A significant question is: What constitutes mathematical literacy, how does it relate to political economy, and how do different conceptions of it relate to the ways school educate students? Mathematical literacy is important because how one understands it strongly influences mathematics education programs, policies, and practices, and has implications for what students learn in school.

Mathematical Literacy

I examine here the meaning of functional and critical literacy as they relate to mathematical literacy, the relationship of mathematical literacy to economic competitiveness, and the meaning of mathematical literacy for different groups of students within society.

Functional and Critical Literacy. Functional literacy refers to the various competencies needed to function appropriately within a given society. All societies need to ensure these competencies. A literacy is functional when it serves the reproductive purposes (i.e., maintaining the status quo) of the dominant interests in society—in the United States, these are the needs of capital. Thus, providing functional literacy for some individuals (e.g., low-paid service workers) could mean a curriculum focusing on low-level basic skills, while for others (e.g., “knowledge workers”4), it could mean a curriculum emphasizing communicating, reasoning, and solving novel, ill-formed problems. But both curricula are functional in Giroux’s (1983) sense:

Literacy in this [functional] perspective is geared to make adults more productive workers and citizens within a given society. In spite of its appeal to economic mobility, functional literacy reduces the concept of literacy and the pedagogy in which it is suited to the pragmatic considerations of capital; the notions of critical thinking [as in critical literacy], culture, and power disappear under the imperatives of the labor process and the need for capital accumulation. (pp. 215–216)

In contrast, critical literacy means to approach knowledge critically and skeptically, see relationships between ideas, look for underlying explanations for phenomena, and question whose interests are served and who benefits. Being critically literate also means to examine one’s own and others’ lives in relationship to sociopolitical and cultural-historical contexts. Although critical literacy includes acquiring or constructing knowledge of particular concepts, ideas, skills, and facts, it is also avowedly political—to help people recognize oppressive aspects of society so they can participate in creating a more just world (Macedo, 1994).

In 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM)5 produced the Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics (i.e., the NCTM Standards). In a critique of the Standards, Apple (1992) argued that there were various social forces involved in creating the Standards, as in any consensus document, and these included politically progressive mathematics educators but also individuals advancing neoliberal corporate interests. In the larger contested terrain of education policy, situated within the overall political, economical, and ideological context, he contended that issues of power were at play and that the intentions of the principal writers (mostly mathematics educators) could not guarantee to what ends the document would be put. Apple distinguished between functional and critical literacies: “Whose definition of mathematical literacy is embedded in the Standards? Literacy is a slippery term. Its meaning varies in accordance with its use by different groups with different agendas” (p. 423). Apple, citing Lankshear and Lawler (1987), contrasted a domesticating, functional literacy designed to make “less powerful groups … more moral, more obedient, more effective and efficient workers” versus a critical literacy that would “be part of larger social movements for a more democratic culture, economy, and polity” (p. 423).

To address Apple’s question about whose version of mathematical literacy the Standards embraced, one can examine the NCTM’s (2000) vision of a mathematics classroom from the Principles and Standards for School Mathematics, the updated NCTM Standards, in which “all students have access to high-quality, engaging mathematics instruction” (p. 3). This is a rich image of mathematical literacy:

Students confidently engage in complex mathematical tasks.... draw on knowledge from a wide variety of mathematical topics, sometimes approaching the same problem from different mathematical perspectives or representing the mathematics in different ways until they find methods that enable them to make progress. … are flexible and resourceful problem solvers.... work productively and reflectively … communicate their ideas and results effectively.... value mathematics and engage actively in learning it. (p. 3)

However, I argue that this vision, which I use as a working definition of mathematical power in this book, as meaningful and comprehensive as it is, tends to act as functional—not critical—literacy because of how U.S. schools are presently constituted. To clarify, by functional literacy, I do not mean a basic-skills, rote-memorization curriculum. Rather, I refer to any set of competencies that does not engender the systematic search for the root causes of injustice, but instead leaves unexamined structural inequalities that perpetuate oppression. This notion of functionality applies regardless of one’s education, and this approach to literacy “even at the highest level of specialism, functions to domesticate the consciousness via a constant disarticulation between the narrow reductionistic reading of one’s field of specialization and the reading of the universe within which one’s specialism is situated” (Macedo, 1994, p. 15).

Thus, it is not the quality of the curriculum or some other evaluative criteria that determine whether a given curriculum (in the broad sense) promotes functional or critical literacy, but rather how it serves the larger educational and sociopolitical structures and demands of society. But while I argue that almost all mathematics curricula in the United States today (be they imbued with mathematical power or with mindless, drill-and-kill repetition) develop functional literacy because schooling tends to reproduce dominant social relations, it is possible to disrupt this—that is, developing mathematical power can serve critical literacy and emancipation. In fact, I contend that this development is a necessary—but insufficient—component of teaching and learning mathematics for social justice, and I explain that in this book.

The Relationship of Mathematical Literacy to Economic Competitiveness. My starting point for examining, from a social justice perspective, the relationship of economic competitiveness to mathematical literacy is its meaning in the original NCTM Standards. The NCTM defined four “new societal goals.” The first was for “mathematically literate workers” for economic competitiveness and market preparedness:

Today, economic survival and growth are dependent on new factories established to produce complex products and services with very short market cycles.... Traditional notions of basic mathematical competence have been outstripped by ever-higher expectations of the skills and knowledge of workers; new methods of production demand a technologically competent workforce.... Businesses no longer seek workers with strong backs, clever hands, and “shopkeeper” arithmetic skills. (p. 3)

The NCTM ended the above section by contending that although mathematics should not be taught solely for work-force preparation, nonetheless, businesses needed highly “flexible” and “adaptable” workers to meet rapidly changing economic conditions.

The NCTM also mentioned mathematical literacy in two of its other new societal goals: “lifelong learning” and “opportunity for all.” In both, the document couched mathematical literacy in terms of economic competition. The “lifelong learning” subsection was motivated by the statement that changing economic conditions demand adaptive workers who therefore need a form of “dynamic literacy” (p. 4). The NCTM then presented its position on equity in the subsection on “opportunity for all.” Although the NCTM stated that “[t]he social injustices of past schooling practices can no longer be tolerated,” the opportunity goal also bound mathematical literacy to economic competition. This subsection ends with, “We cannot afford to have the majority of our population mathematically illiterate. Equity has become an economic necessity” (p. 4). Thus equity itself serves market economics.

From a social justice perspective, there is a significant problem with framing mathematical literacy from the perspective of economic competition. In essence, this positioning places the maximization of corporate profits above all else. This is fundamentally in opposition to a social justice agenda that instead places the material, social, psychological, spiritual, and emotional needs of human beings, as well as other species and the planet, before capital’s needs. The NCTM position on mathematical literacy has multiple facets, but this current is strongly represented. Its voice is authoritative and representative of a broad segment...