![]()

1

AN IDEOLOGY TREE

Sometimes it is best to begin defining something by what it isn’t. This is especially true if a common misconception muddies the waters. From the time Americans began to conduct surveys on public opinion, attitudes about policy proposals have been the central focus. The idea was that democracy is about following the will of the people, so the key is knowing what citizens think about each proposed policy change. There is always a left and a right side, and people who are consistently on the right are conservatives, and the ones who line up on the left are liberals. Citizens have political stances, and ideology is a simple matter of which side of the policy debates they are on. The problem is that both of these assumptions are wrong. Most citizens do not have stable policy opinions about most issues. They are concerned more about their daily lives than following policy debates, so most have not really thought about and decided where they stand on the majority of issues. The second assumption—that ideology is the combination of these policy preferences—is also false, because issue positions do not lead to ideology, but the reverse. Ideology is what makes people hold consistent issue positions. Policy preferences don’t cause ideology; ideology causes policy preferences.

Fifty years ago a professor named Phil Converse wrote a paper that changed how we understand American ideology. The mythology about the paper is that it went around to the major academic journals, all of which refused to publish it because the reviewers thought it couldn’t possibly be right. It eventually appeared as a famous chapter in a relatively obscure book. Converse looked at the evidence from the public opinion surveys that had been growing in number over the previous decade, and realized that most citizens did not have consistent opinions from one year to the next. When asked about current issues, they would not admit ignorance, but just make something up. Perhaps even more important was his discovery that, along with lacking policy views, most citizens did not have an identifiable ideology. Only 10 to 15 percent of Americans were in any way ideological, and most of the rest had trouble explaining what conservatism and liberalism were.1

The reason this paper was almost never published is that it reflects a reality exactly the opposite of the assumptions of most people in government and the academic world. From the perspective of ideological people who took politics seriously in their daily lives, it was unthinkable that other Americans did not follow politics, or have ready policy opinions, and fulfill their role in the academic understanding of democratic theory. But all of the collective evidence since that time indicates that Converse was correct, then and still today.

The lack of a constraining ideology in large part explains the lack of stable policy preferences, as those are often the result of an ideology rather than a building block of one. Few people work out in detail their policy positions on a broad range of issues, which would take a tremendous amount of reading and effort. Even if they did, this process would be unlikely to result in positions that were all conservative or all liberal. It is the reverse process—determining an ideology first—that results in liberal or conservative positions across the board, once the ideology gives us a shortcut to how we should see individual issues. It is the ideology that controls the policy views, rather than the opposite. Once we see that most Americans do not have a hardcore ideology, it follows that they would tend to not have hardline policy views either.

Academics who study public opinion have accepted that most citizens and voters are not ideological, but they have not gotten over their disappointment. For professionals in polling, this led to a dilemma that still plagues the entire industry of public opinion studies: if democracy is about following the policy choices of the majority, how can it work if citizens do not have informed policy preferences? A good question, which is still at the heart of arguments over American democracy among academics.2 We can’t solve that problem here, but one possible answer is that democracy is not about policy preferences after all. In other words, we started by looking for the wrong thing. Democracy is about the core values of citizens, and making sure that our leaders share those values. The central question is the shifting balance in our competing value divisions:

• Do we believe that individuals are responsible for themselves or that society is responsible for the welfare of all of our citizens?

• Do we believe in a more secular or religious public culture?

• Do we accept that military force is a necessary feature of international affairs or believe that we should employ force only as an absolute last resort?

• Should we shun involvement in the affairs of other nations or accept the responsibilities of a superpower to improve conditions overseas and advance our values?

• Should we make a commitment to the environment and the survival of other species as an end in itself or give priority to other interests and commitments?

• Should we embrace traditional roles between men and women, husbands and wives, parents and children, or be open to new understandings and social arrangements?

These questions of core value commitments are at the heart of our politics. In order to see their role in American ideology, we have to discuss the different forms of belief that citizens hold. One description that may be both simple and accurate is an ideology tree.

An Ideology Tree

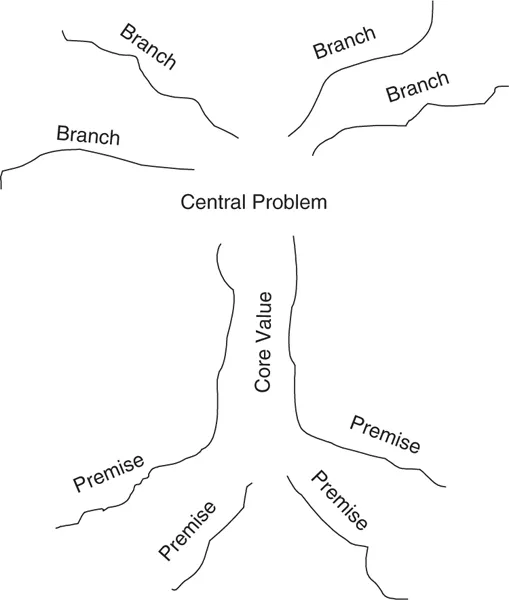

The right metaphor may be the key to explaining something. It is the best image that matches the topic. For example, ideology resembles a tree. It has roots, or foundations, that lead to a trunk, or the main argument. Those create a central question or problem that limits the height of the tree. At that point there are different answers, which lead to the branches or competing factions within the ideology. Conservatism and liberalism are both like this, but have different foundations and distinct core values, which lead to different central questions and then competing answers, or the branches of the ideology.

Figure 1.1 An Ideology Tree

An ideology tree grows from different kinds of beliefs that create a unified worldview. The two key forms of belief that define an ideology are values and premises. The first are statements about how the world should work; the second are observations about how the world does work. Statements of desirable principle and immutable practice—of goals and realities—these are the roots of ideology.

Values

Values are difficult to define, but we can begin with the observation that values need no justification, but we can justify nothing without them. All of our political judgments of right or wrong, better or worse, rely on values. They are “not means to ends, but ultimate ends, ends in themselves.”3 Among the competing priorities for a good society, values are standing judgments of which ones are better. For example, do we believe that tradition is good and a source of stability, or do we embrace new social arrangements that challenge the old status quo, like gay marriage? This is not the same question as what we would ban or enforce, but what in our hearts do we feel is better? Should we publicly respect military people and their service, or should we wish for a different world that does not require military force and shift admiration to nonviolent protestors? Again the question is less about specific policies and more about what we admire.

Another way of thinking of values is that they are the backstops of our decisions. If we ask someone to explain a political position, and then press them to justify that reason, and continue in this fashion, the point at which they can go no further is a value. At some point we arrive at a statement that it feels silly to justify. We reach the baseline position that human life is good, or that you desire individual freedom, or that more equality is better. These are the things that seem obvious to you, needing no justification. They are simply true. They are the core of our belief system, and we are attached to them at a gut level. Hence, values—the most reduced form of justification—can only be believed rather than justified.

In addition to being backstops, values can be thought of as meta-preferences. ‘Meta’ as a prefix makes a word apply to itself, or in this case, preferences about preferences. A simple choice or preference for something is not a value, but a preference about other peoples’ choices is. For example, you might prefer dogs to cats (being a reasonable person). That is a simple preference, but not a political value. If you would prefer that other people prefer dogs, which would be to want a more doggish and less cattish world, that would be a value. Many reasonable people prefer dogs, but have no concern about the expansion of cat lovers; their love of dogs, while noble, is a simple preference. When we move from the realm of personal preferences to public desires, those are values. This explains why a common rejoinder to citizens who oppose legal abortion—that they simply shouldn’t have one—is missing the point. Values are not merely personal choices, but hopes for what is normal or acceptable, public rather than private preferences.

Premises

We began with values, but in some ways it is premises that are the real foundations of an ideological worldview. What is the world really like? More importantly, what are people really like? Basic assumptions about these questions determine perhaps more than anything else how we will see politics. These assumptions are so basic that they seem to defy needing evidence; they are obvious. It may be more accurate to say that they can’t be demonstrated with the available evidence, one way or the other. We simply don’t know the true answers to some of the most important questions. So we disagree strongly, though most people trust their own feelings.

Some of the most influential premises are about human nature. Are people naturally good? Born with innate tendencies to be bad? Aggressive and violent, or by nature peaceful and only driven to violence when pushed? Rational or driven by irrational impulses? Are they simply what they are, or can they change? Does human nature even exist, or are people more malleable than that? The answers to these questions can be thought of as natural truths, or the simple conditions of human reality. But they are not fully separate from values. We can think of statements about what ought to be and statements about what is as fundamentally distinct, but they are intertwined in unavoidable ways. For example, we may believe that military service ought to be publicly admired and highly respected. This is distinct from the belief that the world is a dangerous place and filled with implacable enemies. The first is a value and the second a premise, but they are strongly connected in our belief systems. Premises are not merely facts, but value-laden facts, or idealized facts. Values and premises are intertwined in ways that reinforce each other.

Why individuals hold specific premises is not clear. Perhaps they heard them repeatedly as a child, from parents and other influences. Perhaps they picked up certain premises from the surrounding culture, or from personal experiences that ingrained a perspective on other people. A specific religious tradition could have communicated a premise through its stories and sermons. Hard to say. We don’t know exactly how premises originate, but we do know that people have very different perceptions of how the world works and what people are like—what the real facts of reality are.

Ideology

With the building blocks of premises and values in mind, we can identify a clear definition of an ideology: a specific constellation of connected values and premises that create a vision of a good society. With that guiding vision, the ideology identifies the social changes or government actions that would lead to that better world. A set of policy preferences flows naturally from an ideology, something that has been described as “the conversion of ideas into social levers.”4

A specific grouping of premises and values leading to a political agenda may be the clearest definition, but an ideology is also something broader, what could be called a worldview. It is a way to understand yourself and your position in society, a way to make sense of your story. It is most powerful at its most personal, tying emotions to individual experiences to social possibilities. Ideology can take impersonal events and give them personal meaning. If it doesn’t connect to a sense of your own history, it is likely to mean very little. The famous anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote that “ideologies transform sentiment into significance.”5 They change incomprehensible realities into understandable beliefs.

Table 1.1 summarizes the forms of belief we have identified, or the nature of values, premises, and ideologies. But the most important illustration in this chapter is clearly the ideology tree. It illustrates how our most basic political concepts of premises and values create the cohesive worldview of an ideology. The following chapters explain the four distinct parts of conservative and liberal ideology: the foundational premises, the core values, the central questions, and their competitive answers that divide each ideology into different branches.

Table 1.1 Forms of Belief

| Value | A standing judgment of competing social ends or priorities.A meta-preference (a public rather than private value).A backstop for decision-making. |

| Premise | A belief or assumption about empirical reality.A standing judgment of how people are. |

| Ideology | A specific constellation of values and premises that lead to a vision of a good society or plan for social action, including specific policy proposals. |

![]()

Part I

CONSERVATISM

![]()

2

CONSERVATISM

Premise Foundations

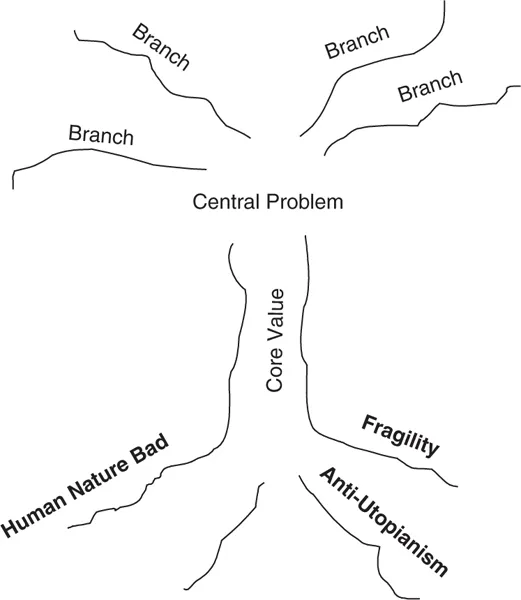

The three premises of conservatism can be thought of as separate foundations that lead to a conservative worldview. They also combine to form a cohesive whole. To accept one of them would lead you toward conservatism; to believe all three virtually guarantees it.

Figure 2.1 Conservative Premises

Fragility

“Are there barbarians at the gate?” The conservative answer to this question is “Yes.” We do have enemies, and they are often at the gates. Perhaps the most basic conservative premise is the fragility of a democratic society.

The question evokes several di...