Chapter 1

Introduction

Defining information and knowledge

A key challenge for any organisation in the twenty-first century is to seek to maintain and improve its performance in an increasingly complex and competitive global operating environment, where change pressures appear to offer the only certainty. Despite the pursuit, over the last two decades, of ‘Total Quality Management’ (TQM), ‘Business Process Reengineering’ (BPR) and more recently ‘Enterprise Resource Planning’ (ERP), to name only three of the more popular management holy grails, there remains, nonetheless, a prevailing sense of failure in fully realising hoped-for levels of improvement. In this context then, it is not surprising that there should be some sense of cynicism when it is argued that, by focusing upon identifying, valuing and managing information and knowledge (IKM) assets, there are significant opportunities to achieve more effective organisations and to improve their efficiency by reducing the amount of wasted time, effort and lost opportunity through better and more integrated use of both tangible and intangible organisational resources. The challenge presented here is to move to define such assets, particularly in relation to a ‘public sector’ context, and through an investigation of the benefits which can accrue from the successful management of information and knowledge, to dispel much of the disquiet and cynicism surrounding this potentially important area of organisational improvement.

Thus, during the course of this text our challenge is to explore what information and knowledge assets actually are, and then to consider strategies for managing them within the particular range of contexts that represent the diverse modern interpretation of the ‘public sector’. To do this is in itself a complex undertaking, for the identification and management of such assets represents a significant challenge. As both a theoretical concept and a management application, such an approach is intrinsically problematic, for what you are attempting to give structure and assign value to is very often intangible: by its very nature it involves people and their behaviour with regard to information and knowledge generation and use.

Such essentially dynamic processes do not readily lend themselves to analysis by traditional accounting methods, nor do they necessarily sit comfortably within established legal frameworks, particularly in respect of issues of intellectual property and the legal admissibility of electronically generated and stored documentation. However, just as in the 1980s when, primarily because of the trend towards large-scale mergers and acquisitions, overwhelming business pressures forced commercial sector organisations to begin to focus on the importance and financial value of their brands, the opening years of the twenty-first century represent a similarly defining moment, in the recognition that information and knowledge assets are potentially key contributors to the achievement of improvement. Therefore, our underpinning premise is that any cynicism generated by the introduction of what might be characterised as yet another management fad is likely to be dispelled, or at least tempered, upon more enlightened understanding of the scope and importance of the management of information and knowledge in an applied organisational context. In order to do this successfully a number of deceptively straightforward principles must be understood, which acknowledge that:

- within organisations there is an imperative for the data generation process to be understood;

- data gathering and organisation for use and extraction of value should then become a priority;

- ‘data’ is transformed into information through appropriate dissemination and interpretation;

- information, when used appropriately, assists in knowledge generation and decision-making processes;

- the culmination of the data to information to knowledge process is the creation of organisational ‘wisdom’, the accumulation of learning processes that help successful organisations to move forward.

During the course of subsequent chapters, each of these elements will be discussed both theoretically and in relation to operational contexts where their integration as processes can be said to illustrate both the benefits and the difficulties of moving towards the development of an IKM-focused organisation.

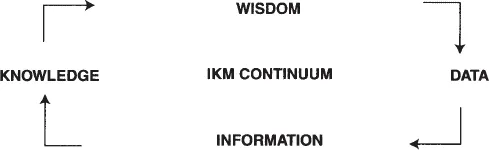

The term ‘information and knowledge management’ (IKM) is in itself an important one, important not only in respect of what we will later discover it capable of achieving in an applied context, but theoretically critical in respect of the linkage that it assumes, as outlined above, between information and knowledge. The simple model, represented in Figure 1.1, from data generation through to information creation, interpretation and use, knowledge sharing and perhaps ultimately judgement and wisdom, is one that we shall explore in greater detail in subsequent chapters. It represents the intellectual and applied foundations of this emerging academic and professional discipline, and is essentially an holistic view, incorporating strategic and operational issues as well as making explicit linkages to areas such as systems analysis and processing, communications and marketing functions, and financial and human resource management. To undertake IKM requires that an organisation be aware of the data/information/knowledge processes currently operating within it, and be capable of and committed to improving the efficacy of these processes through the use of appropriate tools and techniques which emphasise the intertwined goals of achieving collection and connection.

Some of the ‘tools’ mentioned above are the information and communications technologies (ICTs), without the development of which the potential offered by IKM would only ever be partially fulfilled. However, from the outset it is critical to assign these technologies to their proper place in the IKM continuum, and that is very much a supporting and enabling position. Taken together with the fact that senior managers within all types of organisations were (and perhaps the majority continue to be) largely inexpert in their understanding of ICT applications and their organisational implications, the rapid development in the capabilities of ICTs has led to huge investments in ICTs, made globally by all types of organisation, that fail to bring about significant return upon the investment made. In fact, a 1996 research report produced by Mori suggested that some 90 per cent of such investment was so poorly focused upon organisational requirements that it failed to contribute to operating or strategic improvements (Mori 1996). Further, Madrick cautions in his review of the US economy that:

Far from increasing productivity gains, the increasing use of computer technology actually slows them down…Business has increased its investment in computers by more than 30 per cent a year since the early 1970s but the rate of growth of productivity has fallen from 2.85 per cent a year between 1947 and 1973 to about 1.1 per cent a year since 1973.

(cited in May 1998:21)

Figure 1.1 The information and knowledge management continuum

If we consider this in the context of the public sector, the focus for this study of IKM, we can begin to appreciate that globally it is possible, perhaps even likely, that large quantities of public finance have been used in such a manner, since the dash towards the achievement of what is sometimes referred to as ‘electronic government’ has been pursued with much enthusiasm. As Bird argues: ‘Too often they [senior managers and politicians] fall in love with a technological innovation that has no practical use in the real world’ (Bird 1996:78).

Thus it can be observed that ICTs have powerful seductive charms for senior business executives and indeed for politicians. Sometimes their promise is fulfilled, too often it is not: automating a process or function, if that function is not structured appropriately or is in fact not what is required by the organisation or its customers, is not going to improve performance. So, for example, it was interesting to note that in the United Kingdom, during the 1998 celebrations of the fiftieth anniversary of the creation of the National Health Service, Prime Minister Tony Blair highlighted the perceived importance of telemedicine by granting it additional funding for development. While it is too soon to make any qualitative judgements and there is no intention to belittle the potential contribution of this area of health-care development, the question deserves to be raised as to whether this area was prioritised because it represented a key area of strategic priority and development for the UK’s health service, or because the ‘cutting edge’ associations with ICTs were attractive to both politicians and media alike. This question of appropriate investment in technology and the critical importance of ensuring a linkage to wider strategic and operational issues is one that we shall return to many times during our exploration of IKM, reflecting some of the concerns raised by Davenport, who observes: ‘While millions of high-tech entrepreneurs and bureaucrats work 16hour days to improve information technology, virtually no one works on information behaviour and effect’ (Davenport 1996:10).

Setting aside the myths

It is important, then, to dispel at the outset the first of a number of myths that surround IKM: that it is a term that can be used variously as a direct substitute for ‘information systems’, ‘information technology’ or perhaps even ‘decision support systems’. Certainly the ICT element of seeking to manage information and knowledge is an important one, and the competencies required of information and knowledge managers must encompass some level of technological understanding so that they are capable of outlining to technical experts what they need in terms of tasks required. However, too often, particularly when issues of information management (IM) are discussed, it is assumed that they are subsumed within ICT strategies and plans.

It is perhaps the apparent complexity of the processes associated with IKM that has led to a great deal of the confusion around what it actually is, and to the tendency to define it within terms that are more tangible, especially in regard to technology and related applications. The model of information and knowledge management that has been introduced in this chapter is essentially a continuum that represents the relationship between processes: it is an ideal, something that organisations should be working towards but which, as yet, very few have achieved.

As we will see when discussing specific aspects of IKM in greater detail in subsequent chapters, it is certainly possible to identify exemplars of good practice for a variety of aspects of the continuum. The greatest difficulty that we have at present is in identifying an example where sufficient maturity of practice has evolved to represent the holistic or ‘joined-up’ view of IKM that is desirable. This should not be viewed in an overly negative way, for rather than being solely an indicator of the difficulty of operationalising IKM strategies, it is perhaps better viewed as a pointer to the fact that the journey towards managing information and knowledge is never going to represent a ‘quick fix’: it is something that can only be achieved over time. In order to be successful it must impact upon the culture of the organisation, critically on the way in which people work and relate to one another and on the way in which these processes are organised to maximise their potential contribution to leveraging performance. Information and communications technologies can certainly play their part in the achievement of such effective information and knowledge management processes, but only as tools that underpin the achievement of organisation-wide strategies which, like the proverbial spider’s web, link the management of information and knowledge assets to almost all aspects of operations and future planning.

When seeking to define the parameters of IKM, it is also important to consider the very real disquiet that can be generated when discussing IKM among those who view it as potentially having ‘sinister’ overtones. Indeed, academics who specialise in this area have been known to have had the light-hearted charge levelled against them that they are actually in the business of advocating the manipulation of information, particularly that which is intended for public consumption. Managing knowledge has the potential for also being seriously and sometimes mischievously misunderstood, with connotations of thought- and mind-control being put forward by many who do not appreciate the important organisational contribution that can be made by harnessing and formalising the sharing of colleagues’ experiences and thinking on particular projects/tasks/functions. Such sinister connotations are not, of course, the case: the information and knowledge management processes that are discussed here in relation to organisational applications, particularly regarding the public sector, are those which seek to make most appropriate and efficient use of key resources and to ensure that they enhance the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the organisation, particularly in the way in which it interfaces with its customers, be they internal or external.

Once more, terminology has been unhelpful to the cause of IKM, for it is the case, in many public sector organisations particularly, that media and public relations activity is led by public employees with titles such as Information Officer or, still more confusingly, Information Manager. Misleading, manipulating or being otherwise economical with the truth in internal or public fora should have no place in IKM, the role of which is to ensure that key decision-makers, including communities of end-users where appropriate, have the benefit of appropriate information and accumulated knowledge prior to making a judgement and/or decision. The quality of outcome or intent underpinning such judgements is something for which the discipline of IKM should not be held directly accountable.

There are, additionally, significant problems which can arise from the use of the term ‘management’ itself. During the course of the author’s own research into issues of IKM in the public sector, a recurring theme has been the extent to which senior managers, in a diverse range of public sector organisations, have railed against the use of this term ‘management’, particularly as associated with commercial sector paradigms, in connection with the way in which their organisations are structured and operate. To be involved in the process of management, or to be a manager in a government department or hospital perhaps, is often viewed—even today, some two decades on from the first major tranche of public sector reform—as something essentially different from perceived practice in the commercial sector. That there undoubtedly are differences is something that will be discussed later in this chapter. However, it must surely be as true for the public hospital administrator as it is for the insurance company executive that management is fundamentally about giving direction to an organisation, handling and anticipating problems and difficulties, and ensuring that organisational activity is in alignment with the expectations and needs of all customer groups. This is certainly the premise upon which this and subsequent discussion of IKM is based.

Information without knowledge: the road to IKM

It is a truth universally acknowledged, as Jane Austen might have said, that you can seek to manage information without necessarily setting out to manage knowledge. Indeed, there is much to be said in relation to the benefits that can accrue from adopting an incremental approach to implementing an IKM strategy as opposed to attempting to move to a fully integrated approach from the outset.

To consider first the term ‘information society’: it has been with us now for over a decade, stemming largely from the proliferation of data generation, storage and manipulation opportunities afforded by the development of ICTs and the impact that they have had upon the way we live. The fundamental contribution of these technologies has been to enable the gathering and storage of much more data about people, activities and processes than has ever previously been possible. Yet much of what has been captured has been data without purpose: statistical information, personal information that is gathered and retained because it is held to be enough justification that it is possible to do so. Often, such data are capable, upon interpretation and management, of being translated into information, something that has both meaning and possible application and consequent value. In order for this transformation to take place, however, there is a need for information parameters and procedures to be explicitly delineated and, where appropriate, for systems and software applications to be utilised to ensure that relevant data is integrated and organised to achieve the maximisation of appropriate use and relevance. In essence, what we are seeking to do is to create a soil and climate in which both information and knowledge management strategies can flourish. Such an environment cannot be bought from a packet off the shelf; rather, it requires careful husbandry and an acknowledgement, as we have already stressed, that the essential climate for knowledge management to grow and succeed is one where information management has already prepared the ground.

The process of managing data with a view to transforming it into information is a complex strategic one, which should be informed by an understanding of the way in which the organisation itself works. The role of information management, and by association the information manager (although, importantly, the job title itself can vary enormously and in many instances does not yet exist at all), is to determine what can most usefully and ‘profitably’ be gained from interpreting data which, upon human interface, takes on some meaning or application, either in isolation or in combination. The essential identifier of data to information transformation is the assignment of some meaning that is capable of human interpretation.

While theoretically complex, it becomes somewhat easier to understand the logic underpinning this process when it is considered in an applied context. For example, in many countries national or regional governments register motor vehicles on an annual basis. The data that is submitted by individuals is, in itself, often of limited value: it gives details of vehicle manufacturer and model, and the registration address, all primarily of importance in matters of vehicle-associated crime. However, by setting carefully constructed parameters, it is possible, from the mass of data collected regionally or nationally, to extrapolate information that is of greater value: of value to the ‘owning’ department, certainly, but capable too, within an integrated system, of producing supporting information for other departments within the same overarching administration. Indeed, it may possibly extend beyond this and be of value to external organisations. This concept of making use of opportunities afforded by the information-gathering interaction has led some areas of the United States to use vehicle registration processes as an opportunity to encourage citizens to register for local and national elections.

Yet this transformation does not take place miraculously. As yet, even the most sophisticated software products can do no more in their own right than identify trends emerging from data. The parameters for the creation of information from data remain reliant upon the human interface, which is perhaps why the quality and usefulness of the information that is generated are often somewhat variable. As we shall explore in Chapter 2, there is a very real need for an overarching organisational information strategy to give both a foundation and a coherence to the task of extracting, using and managing information.

Knowledge management and its relationship to information management

It is somewhat ironic that although in the late 1990s the terms ‘knowledge management’ and the ‘knowledge economy’ entered the favoured lexicon of senior managers for the first time (KPMG 1998b), for many of them it was without any sense of how their organisations actually managed their information holdings. Without wi...