1 Geosemiotics

Geosemiotics: Discourses in place

A website on California nudist beaches posts the following clarification of legal requirements:

Before the citations were issued it’s clear there’s an ordinance in place and there were notice signs in place and people were clearly violating those posted notices.

‘Ordinance in place’, ‘signs in place’, ‘people were clearly violating’: these are crucial concepts in law and in life, whether we are thinking of nude bathing, crossing against a sign saying ‘Do Not Walk’, or driving through a red traffic light. There is a social world presented in the material world through its discourses – signs, structures, other people – and our actions produce meanings in the light of those discourses.

This book is about the ‘in place’ meanings of signs and discourses and the meanings of our actions in and among those discourses in place. A municipal ordinance prohibiting nude bathing or driving above a certain speed limit is an outcome of a complex and lengthy legal discourse. Meetings are held, investigations made; ordinances are drafted, opened for public comment, passed, and finally posted. All of this legal discourse becomes binding law when and where the signs are posted, when and where the signs become discourses in place.

Or we could put this the other way around: signs are designed by sign-makers, they are made in the shops and workplaces of sign-makers, they are taken out to the relevant site, and finally, some worker puts them up and they become ‘signs in place.’ The sign saying that nude bathing is prohibited has the same words, the same sentences, cites the same ordinances, and all the rest while it is riding in the back of the truck of the worker taking it out to the beach to be posted. During this time the sign may have abstract linguistic meaning but it does not have any binding ‘in place’ meaning until it is actually posted firmly in place at the beach.

This book is called Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. It is a book which deals with geosemiotics – the study of the social meaning of the material placement of signs and discourses and of our actions in the material world. With this title we are trying to capture this ‘in place’ aspect of the meanings of discourses in our day-to-day lives. When we cross a street corner we encounter a complex array of signs and discourses. There are signs regulating vehicular traffic, there are signs regulating pedestrian traffic. We see lines painted on the street: some for pedestrians, some for automobiles, some for electrical workers who are to pull up a manhole to repair the lines underneath. We see commercial advertisements, public official notices, street and building identifications, graffiti, and pasted up notices for legal and even illegal goods and services. As we walk we may be chatting with a friend. This friend and all of the others present are also signs in place which we ‘read’ in taking our actions.

All of the signs and symbols take a major part of their meaning from how and where they are placed – at that street corner, at that time in the history of the world. Each of them indexes a larger discourse whether of public transport regulation or underground drug trafficking.

But this does not only apply to the signs and other symbols posted here and there about our worlds as we go through daily life. Our own bodies make and give off much of their meanings because of where they are and what they are doing ‘in place’. A person who is wearing no clothing on a public beach is a ‘nude bather’ (whether legal or not). A person who is wearing no clothing in the privacy of his or her bathroom is simply a person preparing to take a bath, hardly a ‘nude bather’.

Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World is a book about how we use language in concrete, physical instances: A heavy brass sign means this company is here to stay; a hastily made cloth banner means this sale will not last long; you’d better buy now. Discourses in Place gathers together insights from a wide variety of fields from linguistics to cultural geography and from communication to sociology into a perspective we are calling geosemiotics. We begin with the problem of indexicality.

Indexicality and the indexable

‘What is that?’ cannot be understood unless we look at the world outside of language to fix a meaning for ‘that’ and unless we look at where exactly in the world the person saying this is located as well as what he or she is doing. The meaning of ‘What is that?’ is anchored in a person (who is the speaker?), a social relationship (who is the hearer?), a social situation (what are the speaker and hearer doing – looking or pointing at something?), and a physical world (what is a potential ‘that’ within the spaces of those people?).

The meaning of a sign is anchored in the material world whether the linguistic utterance is spoken by one person to another or posted as a stop sign on a street corner. We need to ask of the stop sign the same four questions we would ask of a person: Who has ‘uttered’ this (that is, is it a legitimate stop sign of the municipal authority)? Who is the viewer (it means one thing for a pedestrian and another for the driver of a car)? What is the social situation (is the sign ‘in place’ or being installed or worked on)? Is that part of the material world relevant to such a sign (for example, is it a corner of the intersection of roads)?

This is the property of language called indexicality. Indexicality has been known to be a universal characteristic of language at least since the turn of the past century in the work of Charles S. Peirce, regarded by many as the founder of the field of semiotics. Indexicality is the property of the context-dependency of signs, especially language; hence the study of those aspects of meaning which depend on the placement of the sign in the material world. In geosemiotics, as in all branches of semiotics, the word ‘sign’ means any material object that indicates or refers to something other than itself. Of course language and discourse are our primary interest and so in that case we would speak of this sentence, this paragraph, or this book as a sign albeit a very complex sign. But we also include signs in the more conventional sense of shop names, traffic regulatory devices, and even the built environment such as roadways – a ‘sign’ that one can and should drive in this particular space. And, of course, we cannot forget that we ourselves are the embodiment of signs in our physical presence, movements, and gestures.

Because indexicality has been most fully studied in relationship to language, we begin with indexicality in language. Language indexes the world in many ways. The most frequently noted indexicals are personal pronouns (‘I’, ‘we’, ‘you’, etc.), demonstratives (‘this’, ‘that’), deictics (‘here’, ‘there, ‘now’), and tense and other forms of time positioning (‘smiles’, ‘smiled’, ‘will smile’). Our understanding of both spoken utterances and written texts must be anchored in the material world. To understand a sentence such as, ‘Would you take this over there,’ we need a provisional location for myself (the speaker – a meaning for here), for ‘you’ (my addressee), for the object (‘this’), and for the goal intended (‘there’).

While anthropological linguists such as Haviland, Hanks, and Silverstein have dealt with the question of how indexicality is structured within languages of the world as a universal characteristic of language, sociolinguists have remained a bit reluctant to enter into the study of the semiotic systems in the material world apart from grammar which must necessarily be called upon for users of language to perform indexicality. To understand the phrase, ‘As we have written above’ we rely upon a semiotics of written objects which tells us that ‘above’ must index

text written within the same document, that it will not be a comment scribbled in the margin but rather in the same general text portion of the pages, and so forth. It does not literally mean ‘above’ (in the air or on the ceiling) if we are writing on a table surface or if it is being read horizontally.

More to the point of this book, to understand the meanings and negations of the sign in image 1.01, we need a theoretical framework which first can take into consideration the telegraphic language of ‘TRAFFIC LIGHT OUT OF ORDER’ to tell us which traffic light is out of order – normally it is the next one the driver will encounter. Hence we need a theory of motion through space and the use of public spaces which will tell us where traffic lights are conventionally located. We also need a theory which will tell us that this sign is negated – it is not to be read (because of its physical position away from the flow of traffic, on the other side of the fence, and in a ‘blocked’ orientation.)

We are calling this theoretical framework geosemiotics to make reference to the social meanings of the material placement of signs (semiosis, to use Peirce’s term) particularly in reference to the material world of the users of signs. For us, as linguists, the primary sign system (semiotic system) is language, though as we have noted above and as we will see in the chapters which follow, mostly we focus on rather simple signs. This narrowing of focus is for two reasons. In the first place, the signs we find around us in daily life are extremely abundant though they have rarely been taken up for analysis by linguists and other specialists in language, discourse, and communication. Everywhere in our world are the logos and brand names on the products we use in daily life and on the shops that line our streets and malls. Wherever we go we see the sociocultural, sociopolitical regulatory apparatus of our worlds in the traffic regulations displayed in painted lines on streets that indicate where we may drive or walk and we see this apparatus in the traffic lights at intersections. We see signs for infrastructural work such as the electrical boxes that run the street lights and we see announcements and notices of events taking place. We see signs saying ‘Post No Bills’ and we see graffiti. The meanings of all these signs depend on forms of indexicality we will take up in the chapters which follow.

While linguistics has given us the most thorough foundation for the study of indexicality in signs, our primary interest in this book is not indexicality in language. This has been and is being widely studied within linguistics. Our interest here is in the ways in which this sign system of language indexes the other semiotic systems in the world around language. That is, we are more interested in the indexable world than in the systems of indexicality in language.

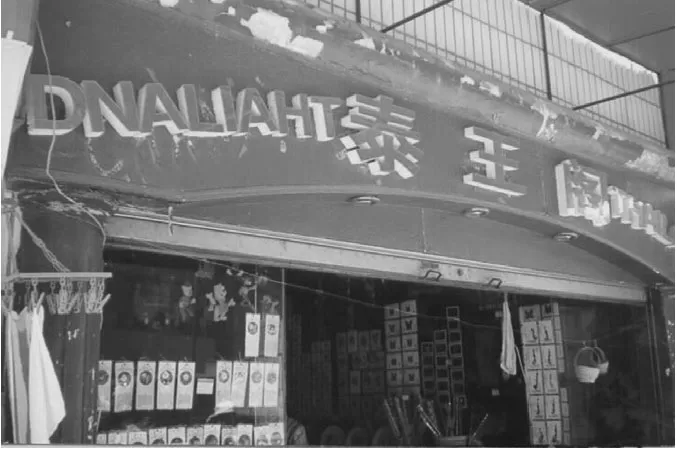

A restaurant in Kunming, China has the sign in 1.02 posted above the door. Native speakers of English generally read this sign as saying, DNALIAHT followed by some Chinese characters. They can make no sense of it. People who are from Taiwan, China, or Hong Kong, however, read this sign as saying ‘King of Dai food [Tai Wang Ge in Chinese] or THAILAND [TAI WANG GE] THAILAND’. For them it is a straightforward sign telling them this is a Dai National Minority restaurant.

What makes some readers try to read this sign in a universalized left-to-right reading path while others read the sign starting from the Chinese characters over the central doorway and then read outward from center toward the margins? Part of this reading is based on knowing Chinese characters, of course, and that is the subject of many books on translation. But more fundamental than the question of translation is knowing how to read the sign in relationship to its placement above the door of a restaurant. Before we can think about what we are reading we have to have a principle to tell us how to read it. We have to know whether we should read from left to right, right to left, or from the center outward. This example illustrates that the first principle in the interpretation of language is to solve the problem of indexability – to locate language in the physical world.

A ‘grammar’ of indexability

Most of the semiotic systems which we index in daily life are completely transparent and invisible to us. Of course the language we use is invisible in this way, at least until it is made painfully visible in those grammar classes in school which so many of us resisted. This does not mean, however, that these all but invisible systems of meaning are unimportant in our lives. On the contrary as Michael Billig has noted in his book Banal Nationalism, it is just these invisible, almost banal, systems of meaning which form the sociopolitical systems that so closely define us and our actions in the world. Billig notes, for example, that we may not talk at all about our nation or even feel that there is any question about nationalism involved in such a simple daily event as the weather report, but as the map appears on the television screen here in the United States we see that there is a sharp boundary between the US and Canada on the north and between the US and Mexico on the south. Canada has no weather, nor does Mexico. The fronts and sweeps of climate are entirely ‘national’, represented as starting sharply at the borders on the map. Sadly for those of us who live in Alaska and Hawaii, both states of the United States, these are also not part of the weather picture. The contiguous ‘Lower 48’ as it is said in Alaska indexes ‘the nation’ in these weather reports in which Hawaiians and Alaskans are marginalized right along with Canadians and Mexicans. With a weather map a political concept is framed; with the definite article the in ‘the nation’ a political entity is flagged as surely as if it flew the red, white, and blue colors of the national flag.

Much of the substance of this book is taken up with the fairly straightforward description of the systems and sub-systems which can be indexed by language and by which language becomes indexable in the material world. Because of the rather compressed nature of this analysis which covers a very wide range of semiotic systems, we cannot in each case also dwell on the ways in which each of these semiotic systems indexes the sociocultural and sociopolitical structures of power in the world around us. Is it of value in and of itself to develop this comprehensive analysis? We believe it is, for two reasons. First of all, as has been well established in the field of linguistics, the grammatical systems of language are among the most visible external manifestations of human cognitive capacities. That is, grammar has been regarded by psychotherapists and cognitive scientists as well as by linguists as a window on the human mind. We believe that it will prove to be highly productive to extend the studies of semiotic systems beyond the analysis of the grammars of languages into the grammars of ‘texts’ taken in the much broader sense that we use here.

Our second reason, however, is for us the more important one. All semiotic systems operate as ‘social semiotic’ systems as we have suggested above in making reference to the ways in which nationalism is flagged in such a simple matter as the production of a weather map. In producing meanings we must make choices; as we make choices we preference one option over another. All semiotic systems operate as systems of social positioning and power relationship both at the level of interpersonal relationships and at the level of struggles for hegemony among social groups in any society precisely because they are systems of choices and no choices are neutral in the social world. This is a point well established in the work of M. A. K. Halliday and many other social semioticians, the analytical tradition within which we place this book.

In this book, of course, we cannot do more than show how three broad systems of s...