![]()

Chapter 1

Landscape – connections and disconnections

Introduction

Most people feel they have a reasonably clear idea of what landscape means. Typically, they think of fine scenery, a painting, a designed garden, an urban park, or perhaps their local green spaces. In reality, even people who claim to be specialists in landscape rarely understand its full range of meanings. Landscape architects, landscape ecologists, cultural geographers, physical geographers, art historians, spatial planners, archaeologists, social psychologists and others use the term in very different ways and often have blind spots about each other’s theories and methods. Landscape is a term that is both disputed between specialists and also difficult to translate between languages.

The origins of the term ‘landscape’ have been widely discussed. Writers agree that the most influential terms have been the German ‘landschäft’ and the Dutch ‘landschap’ (or, archaically, ‘landskab’). It has been suggested that these are, respectively, a geographically ‘bounded area’ and a more visual or artistic ‘perceived area’. Wylie (2007) helpfully explores the ambiguities in these apparently simple distinctions. Different nuances of these terms, and their equivalents in various languages, may imply additional ideas about ownership and belonging, regional identity, and physical morphology. As Wylie notes, dictionary definitions typically converge on the idea of landscape being a portion of land or scenery that the eye can view at once. This notion conflicts, however, with scholarly and professional practices that study landscape ecological processes over ranges of many kilometres, map landscape character across regions, or deconstruct unseen qualities that contribute to ‘place’.

Broadly speaking, different conceptions of landscape locate themselves along a spectrum from a visual and painterly view at one end, where a framed scene with selectively foregrounded features is captured for an admiring gaze, to a more inhabited concept of landscape at the other, where people, land and history combine to create a sense of belonging associated with a mappable region. The extremes overlap extensively – a landscape painting is often of greatest interest for the people, customs or work that it depicts, whilst landscapes noted for their distinctive culture and history will often also be recognizable by their scenery.

Many languages lack a term that adequately translates landscape. Problems even arise in Europe between the Germanic north’s landschäft (landscape, landschap, etc.) and the Romance south’s paysage (paesaggio, paisaje, etc.), whose meanings differ significantly. Over the past century or so, the scientific appropriation of landscape has added new complexities. Geomorphologists refer to landscape as the physical nature of the earth’s surface, on which formative processes operate. Ecologists see landscape as a land–water area larger than the habitat, across which species act out their life-cycle processes of birth, immigration, death and emigration; whilst archaeologists conceive of an area beyond the individual site or monument that is infused with a complementary time-depth. Sustainability scientists refer to landscape as a space possessing multifunctional properties that integrate natural and human ecosystem services, whilst resilience scientists view landscape as an encompassing social–ecological system that is vulnerable to destabilization. Behavioural scientists understand landscape as a human life-space that provides us with affordances for survival and pleasure, and which affect our behaviour, mood and well-being. In terms of creative enterprise, throughout most of civilization, skilled designers have converted land into landscape, using physical materials and plants to create gardens, parks, demesnes, squares and other private and public spaces.

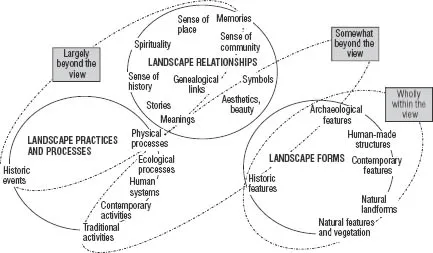

This book concerns the cultural landscape, a term that also lends itself to endless dispute. The European Landscape Convention (Council of Europe, 2000) has defined landscape as an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors – a definition that is now widely accepted by practitioners, although scholars would dissect it mercilessly. Pragmatically, however, it is a useful working definition. The overriding feature is that ‘culture’ combines with ‘nature’, so that human agency becomes an important driver of a landscape’s appearance and functionality (Figure 1.1).

Landscape is different from scenery, although in popular language they are rarely separated; even in policy and technical language the two may be conflated. Scenery is essentially visual – it may simply be enjoyed as a sweep of countryside, or it may be mapped by techniques that identify its characteristics and possibly even quantify its relative importance. The visual qualities of landscape – delightful or dramatic scenery, generally combined with ‘picture postcard’ villages – have, in practice, dominated spatial planning and environmental management policy, despite the occasional statement suggesting a more sophisticated view. Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) has also shown how ‘scenery’ is in part imaginary and illusory, comparable to a staged performance in drama. More recent researchers have emphasized how landscapes have been appropriated and airbrushed, so that they can be commodified for commercial purposes such as promoting tourism and speciality foods.

Figure 1.1 The Peak District National Park, UK: a classic example of a relatively wild landscape that has evolved through an interplay between physical geography and human activities

Landscape, even as a painterly artifice or as a designed area of public realm, comprises far more than the visual, although, given the primacy of sight amongst the senses, it is usually something that people intuitively ‘perceive’. In addition to its perceived properties, however, landscape is rich with stories, nutrient cycles, carbon fluxes, customary laws, economic activities and manifold other mysteries. The crises faced by many landscapes, and the potential of landscape to frame lives, livelihoods, scientific enquiry and public policy, cannot be understood within a narrowly visual conception. An understanding of landscape must go ‘beyond the view’ (Countryside Agency, 2006). The multifaceted nature of landscape – comprising a spectrum of interconnected relationships, practices and processes – is summarised in Table 1.1 and Figure 1.2.

The disconnected landscape

This book addresses a core challenge facing contemporary cultural landscapes. The landscape is more than mere scenery – it is a complex system comprising natural and social subsystems. Its properties derive from the dynamic relations between these subsystems, producing a whole that is more than the sum of the parts. Both in terms of their visual coherence and their unseen processes, landscapes have generally become more ‘disconnected’ in ways that compromise their character, sustainability and resilience. A unifying goal of policy, planning and science is thus to reconnect landscapes in a range of physical and social ways. Physical reconnections, for example, entail joining up vegetated networks within an ecological habitat matrix; social ones may involve recovering links between people and place.

Table 1.1 Cultural landscape: the seen and unseen (based on Countryside Agency, 2006; Stephenson, 2007)

| Practices | Processes | Relationships |

Experience | • the experience of health and wellbeing • creating places that have meaning and identity • hefting and traversing | • localization of culture • globalization of culture • place-making | • meanings, memories, stories and symbolism • aesthetic and spiritual qualities • sense of belonging • in-dwelling |

History | • remanence of former activities and structures | • decay and renewal | • genealogical links • laws and customs |

Land use | • construction • farming, forestry and other land management • energy production and transmission • communication networks | • human influences on air, water and soil dynamics | • formal land ownership and rights • cultural expectations regarding wise use and access across all land |

Natural form | • land drainage and regrading • restoration and reclamation | • landform evolution • soil development and degradation • coastal processes | • sacred sites • inspirational qualities of hills, coastline etc. |

Wildlife | • wildlife management • effects of other land uses on biodiversity • reintroduction and re-wilding | • life-cycle processes of wild species | • ethical attitudes towards nature • cultural perceptions of ‘weed’ and ‘pest’ species |

There is a widely held acknowledgement that cultural landscapes have become fragmented, homogenised and impoverished (Jongman, 2002). Building on this view, it has often been suggested that the disruption of systems that make up the physical landscape, and the erosion of bonds between people and place, might lie at the source of much environmental and social malaise. Unfortunately, these claims have often been made in an assertive way, supported by essentialist arguments about the need for people to ‘reconnect’ with the earth and with the ‘spirit of the place’. This book seeks to offer a more evidence-based case for such arguments; it draws upon a wide range of disciplines regarding the alleged disconnection of landscape, and the theoretical and practical basis for reconnection.

Figure 1.2 Cultural landscape: seen and unseen forms, relationships, practices and processes (based on Countryside Agency, 2006; Stephenson, 2007)

Some of the key types of ‘disconnect’ that have been claimed include:

• | loss of attachment between people and the place in which they dwell; |

• | loss of connection between people and nature; |

• | loss of connections between past and present, eroding the memories and meanings of landscape; |

• | loss of connectivity between ecological habitats; |

• | loss of linkages within and between ground and surface waters; |

• | dis-embedding of economic activity from its platial setting; |

• | lack of effective connectivity in low carbon transport networks; |

• | loss of connection between town and country. |

Variously, these have been associated with declining landscape character, over-exploitation of land and nature, urban flooding, diminishing biodiversity, antisocial behaviour, reduced sense of personal agency, unsustainable modes of energy use and transport, and deteriorating health, fitness and well-being. Indeed, many of the environmental problems around the world have been There is a widely held acknowledgement that cultural landscapes have become fragmented, homogenised and impoverished (Jongman, 2002). Building on this view, it has often been suggested that the disruption of attributed to a profound disconnection between humankind and nature: it is argued that our reductionist tradition has led us to gaze exploitatively on the environment as neutral and profitable stuff, rather than to see ourselves as an inextricable and non-dominant part of ‘nature’.

Hence, various types of reconnection have been advocated, to create sense of place, sustainable drainage, ecological networks, embedded economies, healthier lives and adaptive communities. One of the key problems in justifying such measures, however, is that the evidence for loss of connection and the potential for reconnection is often weak and unconvincing. The idea of local communities identifying with a distinctive landscape is perhaps no more than a yearned-for myth. Indeed, some critics oppose the pursuit of localism, not least because ‘communities of place’ can be bastions of parishpump narrow-mindedness.

This book takes as its starting point the need to examine critically the case for landscape reconnection. It looks at alleged disconnections and their supposed consequences. It explores the arguments about ...