- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Imperial Russia, 1801-1905

About this book

Imperial Russia, 1801-1905 traces the development of the Russian Empire from the murder of 'mad Tsar Paul' to the reforms of the 1890s that were an attempt to modernise the autocratic state. This is essential reading for all students of the topic and provides a clear and concise introduction to the contentious historical debates of nineteenth century Russia.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Russia in 1800

Russia has not been like other European states in modern history. On the political edges of Europe until the eighteenth century, it experienced neither the Renaissance nor the Reformation, and developed eastwards towards the Pacific across barbarous and desolate territory to make it an Asiatic power as well as a European one. It consisted of a country that conquered an empire in which its colonies bordered each other and so relied on a vast military strength to keep control rather than on sea power as west European empires had. Its sheer size, in terms of land mass and population, separated it from other states too as it faced different problems in communications and in mobilising resources. And, until the twentieth century, this slow moving giant used a different calendar and even today it uses the Syrillic alphabet rather than the Arabic letters used in western Europe.

All of this has made Russian history more difficult to understand. In the mid twentieth century, Winston Churchill remarked that ‘[Russia] is a riddle wrapped up in a mystery inside an enigma’.1 Even without the complications of Marxist ideology to make Russia more complex, there remain major problems for the historian of the nineteenth century. First, the legacy of Marxist writings in Russian history remains with its exaggerated emphasis on economic progress and class conflict. Second, there continue to be difficulties in finding good sources of information from a nation that remained mostly illiterate until the late nineteenth century. Thus, from a historiographical perspective as well, Russia has remained quite different.

Political structure

In 1800 Russia was an autocracy and as such was governed by an autocrat who took the title of ‘tsar’ meaning emperor. His power to rule was absolute as there was no parliament, no critical press and very little by way of public opinion. His status was confirmed by the Orthodox Church which assured the people of his divine right to rule on behalf of God, and Article I of the fundamental laws stated ‘The Emperor of all the Russias is an autocratic and unlimited monarch. God commands that his supreme power be obeyed out of conscience as well as fear’. Thus, there was little need to issue laws other than by decree and the tsar was the final judge of all policies. His main tasks were to defend Russia from foreign attack and to maintain order within the frontiers and this was something that the Romanov dynasty had been doing since 1613.

In practice, however, the tsar was not entirely free to do as he chose. He was akin to the chief noble whose power was limited by that class and during times of crisis or misrule he could be extremely vulnerable. The Russian system of absolutism was tempered by assassination. Usually, it was the nobles that carried out the task (in their own self-interest) but not always. Thus, Catherine deposed Peter III and then consented to his murder in 1762. Tsar Paul was strangled by army officers acting on nobles’ instructions in 1801 and Tsar Alexander I was blown up by a section of the educated élite that claimed to be acting on behalf of the ordinary people in 1881. The nobles expected privileged treatment for their support of the tsar and they got this in the form of exemption from personal taxes and ownership of serfs. The reluctance of nineteenth-century tsars to free the serfs reflected their fear of provoking the nobles’ wrath.

The concentration of power in the hands of the tsar was designed to assert Russian control over a vast and unwieldy empire which he did not have the economic or technological resources to enforce by means other than fear and deterrence. Only by demanding total obedience to himself, endorsed by the Church and backed up by a brutal army, could the tsar hope to keep together an empire that stretched from Poland to the Pacific, from the Arctic Circle to China. It was Russia’s enormous size that gave it strength in the nineteenth century but it was also this basic fact that was its main weakness. It was never easy to control a large, sometimes restless and often remote population. And the nobility were only committed to the tsarist system while it functioned successfully since it upheld their rights as lords of their own estates and gave them considerable local power.

To help him in his rule, the tsar usually enlisted the support of a small number of advisers drawn from the nobility. One of these might emerge as a chief minister periodically, as Speransky or Arakcheyev did under Alexander I, but their hold on power was always precarious and entirely in the gift of the tsar; just as they were responsible to him so they were dependent on him. As many as ten to fifteen further advisers might be used, possibly as the heads of government departments, but equally there could be as few as four or five – as at the start of Alexander I’s reign or during that of Nicholas I. Even the structure and organisation of the highest level of government was decided by the tsar and, since so much hinged on his character and preferences, changes could be rapid.

More consistent features of the autocracy were the chief institutions of the state which carried out its policies. The three elements here were the church, army and bureaucracy. The first of these was the Russian Orthodox Church which had split away from the Greek Orthodox in the fifteenth century. It had been rendered powerless in the 1760s when its lands were nationalised, or confiscated, by the state so as to secure a cash income. By 1800 it had become part of the government system, funded by it and used by it, to disseminate information into every village as well as to instruct the inhabitants to remain obedient to the tsar. Indeed the insistence on divine right included special claims for ‘holy Russia’ as the tsar was seen as a ‘little father’ who cared for his people in a God-like way. Similarly, Moscow was seen as a “Third Rome’ or holy city after the failure of Rome and then Constantinople to provide a haven for Christianity from hostile armies. The leader of the Church was the Over Procurator of the Holy Synod, a layman appointed by the tsar from the early eighteenth century, which ensured effective state supervision.

The army numbered 3–400 000 men in 1800 but from 1812 and for much of the century stood at about one million. It was composed primarily of serfs who were often drafted into it as a punishment. Its military capability lay in part in its size since it could use attrition; Russia’s manpower reserves were unlikely to be depleted before those of an enemy. However, it could also fight with skill under the command of officers drawn from the nobility. Tactical retreats were used to finally defeat Napoleon in 1812 and they could attack very successfully too as the succession of victories against Turkey and neighbouring states in Asia demonstrated during the nineteenth century. It was a huge drain on the government’s limited finances, though; in 1815 it accounted for about one-third of all revenue.

The bureaucracy was an alternative career for those members of the nobility who did not enter the armed forces or whose estates could not support them. Russia’s civil service numbered up to 20 000 in 1800 and it was based mostly in the two main towns, Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Its efficiency might be doubted, though, as in the 1810s the Minister of Justice, Troshchinskii, observed that for most everyday needs ‘the greater part of the population of the state depend almost exclusively on local institutions’. It was the task of the tsar’s provincial governors to keep him informed and, above all, to maintain order in each of Russia’s fifty or so provinces. Compared to western Europe the bureaucracy was under-manned too.

Social structure

The social hierarchy in Russia closely reflected the political order, with the tsar and his court at its pinnacle and then a series of tiers of successively greater numbers of people reaching down to the serfs and peasants. The intermediate groups included the nobility, Church, army officers, merchants and bureaucrats each of which could overlap in terms of wealth and status, but despite this Russian society was not complex. Its most complicating feature was the diversity of nationalities within the empire.

The nobles amounted to just one per cent of the population. They were composed of an élite aristocracy with large estates and access to high government positions, and a lesser gentry class with smaller landholdings and fewer serfs. The aristocrats could typically trace their ancestors back almost a millennium to the foundation of Russia and they often took the title of ‘Prince’ (as did members of the royal family) although this might be translated as Grand Duke. Titles were inherited by all children. The nobles had effective control of their large estates since they enforced order and obedience among the serfs and in practice they were the most powerful individuals in the Russian Empire’s provinces. The provincial governors were, of course, drawn from this class too.

The gentry were a lesser class but often lent their name to include the nobles. They held land which might be worked by a few dozen serfs but was very unlikely to exceed one hundred; about one-third owned fewer than ten serfs. Like the nobles, their social status was diverse, but it was the wish of many to advance up into the higher echelons of the hierarchy and the usual routes of advancement were the armed forces and bureaucracy. Although service to the state was not compulsory in 1800, many still spent some time working in this way. Thus, the social strata were woven into the framework of the state’s institutions. The gentry (and nobles) were the political nation of Russia since they wielded considerable influence over the tsars despite not formally having any right to vote for either central or local parliaments. Their power was that much greater because of the absence of any significant middle-class too. Russian economic development was based on expanding traditional agricultural and manufacturing practices rather than innovating and changing the way they were organised. There were therefore almost no factory owners and the commercial middle class was composed of traders; among these were many Jews based primarily in Poland.

The clergy belonged mostly to the Russian Orthodox Church although there were some Lutheran (German Protestant) groups along the Baltic coast. Each village had a priest who remained with it all his life. He was allowed to marry (but not to re-marry) and his main function was to perform religious ceremonies – baptisms, marriages, burials – rather like a clerk or administrator. There was little by way of Biblical teaching since the level of education most priests achieved was quite low, but many of the sacred texts were related and even recited to the village. The clergy’s income was made up of fees for the religious ceremonies and from their own farming practices since each priest had some land of his own. Above the village priests was a hierarchy of bishops as well as a tier of monks from whom the prelates were selected and this was the main distinction in the personnel of the church; between the ‘black clergy’ at the village level and the ‘white clergy’ or monks. The church as a whole received about four million roubles a year from the state (one per cent of its revenue) and this supplemented the priests’ incomes too, albeit in a rather meagre way.

By far the largest group in the population was the peasantry which was composed of two main groups; the serfs and the state peasants. As with the nobles and gentry, the terms serf and peasant are often used interchangeably, but this is misleading. The serfs were privately owned labourers who could be bought and sold like livestock and amounted to almost half of the entire population. The state peasants belonged to the state (rather then to the royal family) but were in the gift of the tsar and they were often given away to nobles as a reward for services rendered; they accounted for 40 per cent of all rural workers. The Romanov family and the Church also owned a number of peasants amounting to some 10 per cent of the workforce. Altogether, the peasants and serfs made up 90–95 per cent of the population and it was therefore their labour that generated Russia’s wealth.

Not all of the empire operated a servile economy, though. It was concentrated in European Russia, west of the Urals, and new territory that was acquired through conquest was by no means certain to be subjected to the system. Even within the areas in which it operated there was diversity since in the far north as few as six per cent of some villages were populated by serfs but in the provinces around Moscow the proportion was 70 per cent. The reasons for such differences were mostly strategic; in areas where Russia did not fear attack, there was little need to tie labourers to a particular estate but in the heart-lands of Russia the tsars had been keen to a hold on potential recruits to the army.

Conditions for the serfs were grim. Their masters had the right to sell them, flog them, exile them to Siberia or send them to the army for a typical twenty-five year period. Most serfs worked the land for their landlord (sometimes for six days out of seven) under a system called ‘barschina’. It was most common in the black earth belt in the southern part of European Russia where the soil was fertile since lords wanted to maximise their own harvests. It could also extend to serfs who had to work in the lord’s household as a domestic servant, and 200 000 were in this situation. Alternatively, serfs might work under the ‘obrok’ system in which they paid their lord cash (or goods) instead. This method allowed serfs to work in industrial jobs either on the lord’s own estate or in a nearby town.

Working conditions were very difficult in either situation since the bulk of the landowners did not run their estates efficiently; the money that the state lent to them on the strength of their assets was often squandered on luxury goods rather than invested in new equipment or better farming practices. The workers themselves had little incentive to increase production beyond their own immediate needs – even if they had the ability to improve their land – since any surpluses were likely to be taken from them. However, there was little scope for them to improve their lot since there were desperately few schools. In 1800 there were no more than 70 000 children receiving primary education and most of those were in towns, so the level of rural literacy was extremely low – well below five per cent even in European Russia.

Taxation fell especially hard on this group, the poorest of all Russia’s people, since it had to pay a poll tax (from which the nobles were exempt) and it paid again through taxes on alcohol, where the state operated a monopoly on vodka production. Over half the government’s revenue was raised through these two taxes. The plight of peasants and serfs often became desperate and it was not surprising therefore that they could become restless and unruly in times of particular hardship; riots and violent protests were endemic to the Russian countryside.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that Russia’s population was not just made up of those of Russian extraction. By 1800, it included many ethnic and national groups such as the Germans living along the Baltic coast, Poles, Jews and Finns in Europe; and in Asia there were tribal groups that stretched across Siberia and about which Russia knew little. Nor were all Russians quite the same. There were ‘Great Russians’ whose focus was Moscow, ‘Little Russians’ based in the Ukraine and Kiev, and ‘White Russians’ who lived in Belarus. Cultural tensions between these groups remained from their medieval past. A further group that considered itself at least semi-independent was the Cossacks who lived in the southern lands of Russia and who had a reputation as excellent cavalrymen. By 1800, their autonomy was much reduced as they were obliged to fight for the tsar, and their skills on horseback were probably exaggerated. Still, they added to the diverse nature of society under the tsar’s control.

The Russian economy

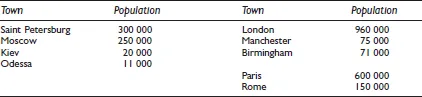

If the great size of Russia was its main weakness politically, then conversely this was its great strength economically. The vast expanses of territory were difficult to control but they were inhabited by huge numbers of people. With a population close to forty million in 1800, Russia was by far the largest of the European states. Its closest rival was France with just 27 and then Austria with 25. However, estimates do vary as to how large Russia’s population was because it is difficult to find any statistical sources that are reliable. The first census was taken as late as 1897 and, despite the large bureaucracy, even this missed out entire provinces. Consequently, surveys of the Russian economy at this time tend to focus on characteristics rather than on ratios or figures; they tend to be qualitative rather than quantitative. Approximately 95 per cent of Russia’s people lived in the countryside and even the main towns were quite small by western European standards.

The Russian economy was overwhelmingly agricultural. The system of farming for both serfs and peasants was based on the village community or ‘mir’ which operated an inefficient three field rotation of crops that had been developed in the middle ages. This meant that many areas of Russia were unable to manage anything more than subsistence farming and that they were vulnerable to periodic famines. The worst problems of this kind occurred in 1891–2 and 1898. By contrast, there were some quite fertile areas such as the black earth belt of Great Russia and the steppes of the Ukraine which produced grain surpluses that were then transported to areas of shortage, but the size of the empire and the difficulty in moving goods of any kind through it meant that shortages persisted.

Table 1.1 Comparison of Russian and west European urban centres, c.1800

Transport links were poor. Roads were merely earth tracks of varying widths that were adequate in the warm summer months but became muddy or impassable in winter. Water-borne transport was difficult too since Russia’s coastline was not continuous and its northern reaches (both in the White Sea and the Baltic) froze in winter. This same problem applied to many of its rivers which prevented barges distributing goods efficiently. Moreover, the warm water ports that Russia acquired on the Black Sea during the eighteenth century were very far distant from the main population centres. The route from Azov to Moscow was over 400 miles for instance. There were no railways, of course, until the 1830s and Russia was among the slowest of the European states to adopt them.

The severity of the Russian winters also left large tracts of its land unusable and the inhabitants impoverished. Parts of Siberia were subject to perma-frost that never melted and anyway access was difficult through dense forests. Moreover, in the outlying regions of the empire Russian control was not complete and local disputes with frontier tribesmen or hostile local populations meant that economic development of newly acquired areas could be very slow. This was true of Poland and especially the Caucasus.

Russia’s most obvious economic asset was a mixed blessing. The system of serfdom was enshrined in law by Tsar Alexis in 1649 to ensure the security of the nobles’ estates while ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyrights

- Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Russia in 1800

- 2 The reign of Alexander I (1801–1825)

- 3 The reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855)

- 4 The reign of Alexander II (1855–1881)

- 5 The reign of Alexander III (1881–1894)

- 6 Epilogue, Russia 1894–1917

- Glossary

- Further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Imperial Russia, 1801-1905 by Tim Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.