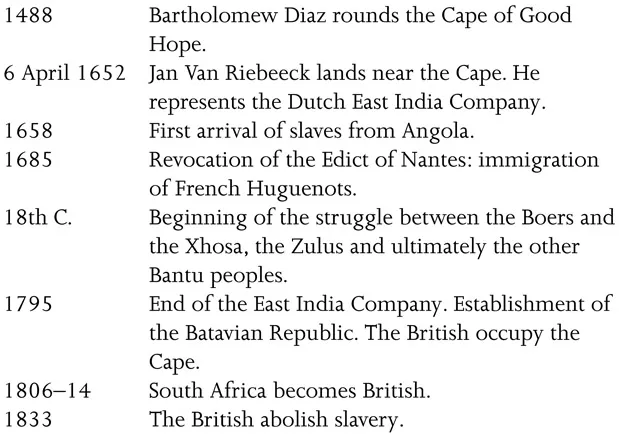

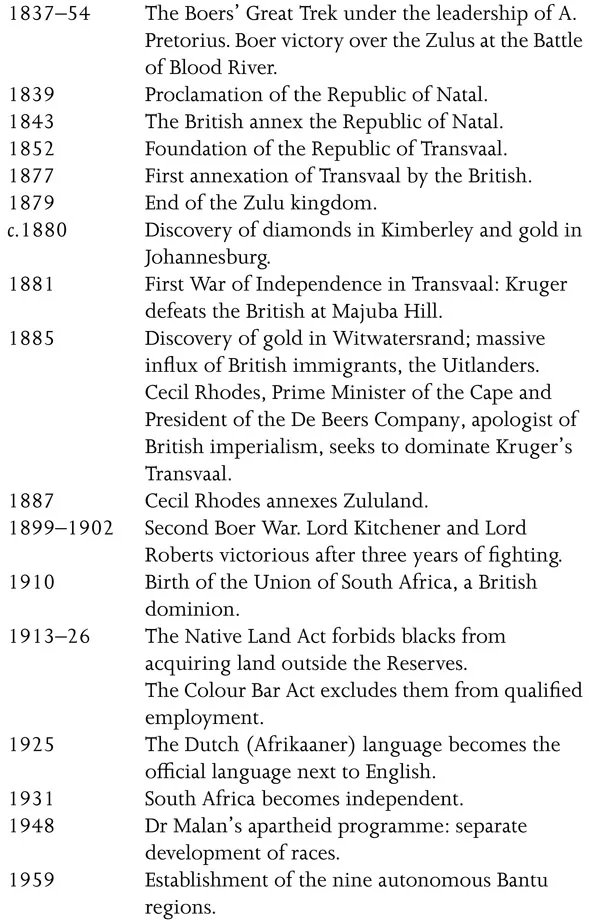

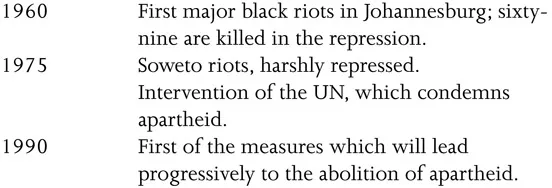

Chronology

‘White’ history is moribund; but the ‘whites’’ history is not.

Selecting systematically the school textbooks of several European nations, Roy Preiswerk and Dominique Perrot have made up a record of the stereotypes underlying this ‘white’ history, the principles behind its periodization, the principal values stressed by the whites in comparison with the rest of the world – respect for law and order, national unity, sense of organization, monotheism, democracy, settlement, industrialization, the march of progress, etc. Much of the same can be found in every European country.

However, during the last half-century this type of history has been under scrutiny. True, the very attack on it has, in a sense, been ‘white’, but, nevertheless, it is clear that the struggle for independence from the colonizing world has been the principal agent of a far-reaching revision. Against the overwhelming pressure of History in process, ‘white’ history has conceded ground; but only step by step, and in proportion to the process of decolonization.

During the 1950s, for example, as Denise Bouche notes for the history of Black Africa, some minor concessions were made in the school textbooks: the Toucouleurs of El Hadj Omar, who had resisted the French conquest in 1870, are no longer called ‘fanatical Moslems’; while Omar no longer ‘pillages’ the Bambouk, he ‘conquers’ it. Even in the former colonial powers, diplomatic expediency and prevailing fashions required a more considerate policy. For example, in 1980 there disappeared from the French third-form textbook, Hatier, an illustration from 1907 showing some Moroccan corpses in Casablanca: it had as its caption, ‘A street after the passage of the French.’

However, if in the West this sort of history is disappearing in the textbooks, it remains alive and well in the collective consciousness. There will be many opportunities to demonstrate this.

Yet, apart from South Africa, there no longer exists, as such, a ‘whites’’ history, whether in Europe or, obviously, still less intact, outside it; it is disappearing by itself. In the extra-European world seeking to bring its cultural past back to life, there survives hardly more than a single ‘whites’’ history in its pristine conditions: only that which is taught in the country of apartheid, to the little white children of Johannesburg.

In the Africa of the Afrikaaner, history is not only a matter of ‘white’ origins which, in the words of Frantz Fanon means ‘the history of the white man and not those whom he oppresses, rapes, plunders and murders.’ History also draws equally upon the ‘Christian’ tradition: the Bible and the rifle have always been, for the Boer, in those huge open spaces of the country, the companions of his fear and solitude.

A statement by the ‘Institut vuur Christelijke-nasionale Onderwijs’ (ICNO) epitomizes both the Christian and racist objectives of history teaching: it dates from 1948 and reiterates formulae or themes which had already been launched in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when J. A. de Mist, having attempted, vainly, in 1804, to laicize education, found his reforms attacked and then annulled.

The instruction and education of white children must be based upon the conceptions of their parents, hence it must be founded upon the Holy Scriptures … love of what is our country, its language and its history.

History must be taught in the light of revelation and must be seen as the accomplishment of God’s will (Raadsplan) for the world and humanity. We believe that the Creation, the Fall and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ are historical facts of capital importance and that the life of Jesus Christ is the great turning-point in the history of the world.

We believe that God willed separate nations, separate peoples, and gave to each its vocation, its tasks and its gifts. Our youth can only continue, in faith, the tasks of its elders if it has a knowledge of history, that is to say, a clear vision of the nation and its heritage. We believe that after our maternal language, a patriotic history of the nation is the only means by which we can love one another.

From the Great Trek to Marco Polo

The fundamental event in Afrikaaner history, apart from the arrival of the first colonists, is the Great Trek of 1838. The Great Trek was the decision of an entire people to migrate across the country, in search of a land of refuge from the English, who had been masters of the Cape since 1815.

The Boers therefore wanted to maintain their beliefs, keep Afrikaans as the official language, maintain their traditional way of life and their ‘traditional’ modes of relations with the blacks, which the English intended to reform by giving to the Hottentots an equal status to those of the whites:

That was contrary to the law of God and opposed to the natural differences of race and religion. For every good Christian such a humiliation was intolerable: that is why we have preferred to separate ourselves in order to preserve our doctrines in all their purity.

This conception of the relations between blacks and whites was written in the constitution of the first Afrikaaner Republic of Transvaal, founded in 1858: ‘There will be no question of equality between Whites and non-Whites, whether in the Church or within the State.’

For the Boers, the Great Trek, this Anabasis of several years, was, in the words of Marianne Cornevin, the precise equivalent of the Exodus of Moses, the search for the Promised Land. Its route is sacred and so are the dates and places through which it passed, such as the day on which Andries Pretorius made his call to the Almighty, the Geloftedag, when the Boer people contracted their pact with God. Inspired by this oath, they carried offa brilliant victory against the Zulus, at Blood River, and thirty years later the Boers restored the camp (laager) which had sheltered them during the battle. Later on they also restored the place where, in 1880, they fought their first war of independence against the English, who wanted to lay their hands on Transvaal: the late Lord Milner, who appreciated the symbolic significance of such objects, had had most of the place thrown into the Indian Ocean.

Thus these places, these stones and objects made up the triumphal stages of Afrikaaner history; in the children’s history books there is a whole chapter given over to cataloguing them. This is a unique example. History in South Africa is as much a pilgrimage as an understanding of the past.

The voluntary decision to depart, the Great Trek, bore witness to the will of the Boers not to be oppressed by laws and customs contrary to their convictions. This symbolism imbues the spirit of their entire history.

Thus, the very choice for the opening chapter of the history book used in the fourth form: astonishingly, it concerns none other than … Marco Polo. The apparent function of this chapter is to place South Africa on the great routes of the voyages of discovery. But the facts which precede this show exactly why Marco Polo turns up in this way in Johannesburg, and we become able to read this chapter in a different way, to see it as a sort of premeditation on the events that will follow.

How would you like to leave your country at the age of 19 to go on a journey that will last 24 years?

How would you like to visit an exotic country and become very rich?

How would you like to see strange things that you’d never seen before?

Our story begins a very, very long time ago, more than a thousand years before your great-grandfather was born. At that time people did not go far from the village of their birth, for it was very burdensome and very dangerous to travel.

There were some people, however, who went on distant journeys, pilgrimages; they returned to the Sacred Places, the most popular of which, although it was also the most difficult of pilgrimages, was the Holy Land, Palestine. There, the pilgrims met Arabs who slept on mattresses, and not on straw; who had spiced foodstuffs and all sorts of luxurious objects, such as silk, velvet, carpets and perfumes. Imagine what stories these pilgrims could tell when they returned to their country. In 1071, Jerusalem, the Holy Land, was captured from the Arabs by a people of warriors called the Turks. A large number of soldiers took part in these Holy Wars, or Crusades, against the Turks, before the Crusaders, in their turn, came to know the riches of the Orient.

The merchants of Europe, and above all the Italian towns of Genoa and Venice, predicted a huge demand in Europe for luxury goods, especially spices and silks. These were expensive products, for the merchants had to take great risks to get them and were often attacked by wild beasts or else by ferocious tribes, such as the Tartars.

It was at this time that Marco Polo left for his great voyage.

Marco Polo came from Venice, which was a very strange place to live in, for it had canals in place of streets. We would find the world a very odd place at this time for there were neither cars, nor planes, or even steam-ships then and nobody had even yet heard of South Africa. Even if we found ourselves in England, we would find it very hard to understand their language.

One day, Marco Polo’s father and uncle, who were both merchants, left on a long business journey. As the years went by, and they failed to return, people began to believe that they had died. Nine years later, however, they suddenly reappeared in Venice and told of how they had discovered a marvellous country, called Cathay. Imagine how Marco must have marvelled when they told him of the wonders they had seen. He must have become even more excited when he learnt that Kublai Khan, the king of Cathay, had invited his father and uncle to return. Perhaps they would allow him to go with them.

And Marco Polo did go with them, two years later.

A whole host of surprises awaited Marco Polo on his arrival in the capital of Cathay. The first was the fact that they used paper for money. Nobody had ever heard of such a use for paper in Europe, for at that time printing had still not been invented, while the Chinese had practised it for centuries. Another strange custom was the nightly curfews. Nothing was spared to make Kublai Khan’s palace the most beautiful in the world. And what wonders there were … ferocious animals and stables packed with thousands of white horses. Everywhere craftsmen were busy making silks and carpets; and here and there one might see an alchemist changing metal into gold or finding the elixir of life. Banquets and celebrations were continually taking place.

After he had been some time in the capital, Khanbalik, Marco Polo was asked what he found most surprising about China. Do you know what he replied?

His reply was astonishing.

To Marco, who came from a country, Venice, where only one religion was practised, it was amazing to see a king who allowed his subjects to practise different religions. Amongst Kublai Khan’s subjects, there were Christians, Buddhists, Jews, Hindus and Mahommedans …

Virtues and Courage of the Boers

South Africa, land of liberty and religious tolerance: such is the first impression young children are given of this country. This introduction to history, with that reply by Marco Polo, is reinforced by other factors – the arrival of the Huguenot refugees, who escaped from Louis XIV, and of other countries’ citizens, to find liberty in South Africa. It was these free citizens who made up the nation and who, later, in their struggles against the English came to attach less importance to gold and riches, than to the more noble values of the faith…. South Africa was a land of tolerance and welcome, but she was also a daughter of necessity.

Since the Turks were barring all routes to the Orient, western merchants had to look for alternative routes to Asia. Sailing down the African coast, the Portuguese became the first to reach India by the south and the west: ‘This is why our country has many ports with Portuguese names.’ But they did not stay long ‘for, conflict having broken out with the Hottentots, the king of Almeida and sixty-nine of his men were killed during a struggle to regain their ships anchored off the coast.’ From that time on, the power of the Portuguese began to decline, while the English and Dutch were beginning to exploit the same route.

Up until that time, the Portuguese, who had become extremely wealthy through their trade with India, kept all its benefits to themselves, and the route to India was a closely guarded secret. The Dutch had to content themselves with retail trade. When in 1580, Philip II, King of Spain and Portugal, closed Lisbon to the Dutch, it was a devastating blow to them, for the Dutch depended upon this commerce. They were forced to seek the route to India by themselves. Hardy sailors, they thus came by our country.

After the death of Almeida, the Portuguese were too frightened to remain in South Africa, because of the Hottentots, and so the place became free; the Dutch thought the Hottentots might well be disposed to do a deal with them, particularly in the exchange of cattle. In spite of the mistrust of the Hottentots, they established themselves here. Some fifteen years later, in 1652, 200 Dutchmen, led by Jan Van Riebeeck, founded the first permanent establishment of South Africa. This is why 6 April is a national holiday.