eBook - ePub

Learning Citizenship

Practical Teaching Strategies for Secondary Schools

This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Citizenship curriculum aims to help young people to participate more fully in society through the development of a range of relevant skills and knowledge. This book shows how a variety of teaching strategies can be used to teach citizenship skills across a range of curriculum subjects as well as in Citizenship lessons themselves. Topics covered include:

- developing discussion

- thinking through debate

- addressing controversial issues

- investigating citizenship

- learning through role play

- working in groups

- learning with simulations

- participation.

A lively and practical book which will be invaluable to student teachers and their trainers, Citizenship co-ordinators in schools and advisors across the country. It combines issues of pedagogy with real classroom experiences and demonstrates just how students learn from different teaching strategies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Learning Citizenship by Paul Clarke,Jenny Wales in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Reflective teaching, reflective learning

Thinking about Citizenship

Teaching Citizenship is often different from any mainstream subject experience. In the National Curriculum, Citizenship appears as a discrete heading. It expects schools to provide students with opportunities for participation as well as the knowledge and skills components; and it asks them to develop whole school programmes. It is therefore formalising many of the things that schools already do and asking them to incorporate them into a Citizenship framework.

Some schools already have well-established programmes and the National Curriculum guidance offers some clear links to subject Programmes of Study. Personal, social and health education (PSHE) and Citizenship Units of Work are offered on national websites to support specialist Citizenship lessons through the Key Stages. The decisions to be made are about ‘where’ and ‘when’ to teach particular aspects of citizenship.

Schools are using a wide range of strategies, both across the curriculum and within specific subject areas, which take into account students’ experiences in different school and community contexts. This book suggests ways in which a range of activities can be tried and developed in different contexts in schools in order to create a successful whole school strategy. Different chapters show how teachers have worked in and across subject classrooms to explore Citizenship with their students.

The process of reflection-in-action (Schon 1983) requires a thoughtful approach, some systematic use of evidence about students’ learning and time together with others to explore the issues. Some of the factors that contribute to reflection in action and a thoughtful approach are:

- sharing an interest in Citizenship activities and their consequences for the school community

- being open-minded, responsible and whole-hearted (Dewey 1916) about Citizenship

- recognising the value of reviewing their own practice, using evidence from classroom enquiry and other research

- enjoying collaboration and dialogue with teaching colleagues

- looking for creativity in the development of teaching and learning strategies for Citizenship.

Key questions for reflection

There are masses of resources for the classroom and extra-curricular activities to support Citizenship (National Curriculum 2003) but making the best use of them requires a thoughtful approach on the part of individual teachers and Citizenship co-ordinators. Chapters in this book provide ideas for using such resources to develop different kinds of Citizenship skills and understanding in students. Later chapters look at strategies for working together across school and beyond school to encourage more active participation on the part of students in both their school and local communities.

Reflection means asking thoughtful questions about what is happening in the classroom and beyond. The questions are familiar to all in the context of existing subject teaching.

- What do I want students to learn?

- How can I ensure thoughtful learning?

- How can I find out what students actually learn?

- How does Citizenship learning in my class fit with learning elsewhere?

- How can I work with other teachers to answer these questions?

Each chapter ends with some questions and tasks which are designed to help teachers to apply the ideas in the case studies to their own schools.

Active learning

In preparing students for Citizenship, school experiences must help to shape their future action and help them to make sense of new ideas. This can be achieved through active learning that helps students to draw on their previous experiences in order to understand and evaluate new ideas. It involves making new ideas accessible (Bruner 1966) by relating them to students’ previous experiences and providing carefully constructed steps or scaffolding to support learning.

Students at John Cabot School in Bristol, where Citizenship is incorporated into Information and Communication Technology (ICT), were trying to understand why the plight of asylum seekers caused so much debate. They had little knowledge of the reasons why people were seeking asylum in the United Kingdom so they were guided through an investigation using the BBC website. In the process they became more informed about individual stories and the changing numbers of applications from selected countries. Students were asked to create an informative leaflet of the kind sent out to the public by a government. They had to exercise selection skills because the word count was limited and to try to understand how asylum issues were seen by a government rather than by an individual. Finally, they were invited to express their views to their local Member of Parliament (MP) via email links made in an earlier unit of work. The learning embraced knowledge, skills and participation.

Developing the scaffolding in Citizenship

Asylum seekers in an ICT lesson

Staging of experiences:

- start with case study of a young asylum seeker’s story with strong narrative

- emphasis on empathy

- use data from website to broaden understanding; how typical are these people of asylum seekers; more objectivity expected

- write a summary report for a given audience; requiring higher order skills.

Activity means ‘do and review’

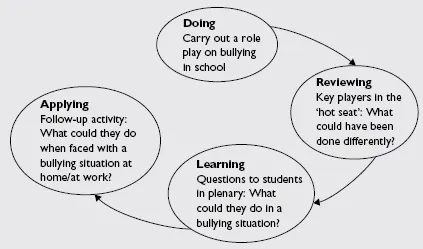

Doing, reviewing, learning and applying (Kolb 1984) highlights the importance of activity to

- engage students

- encourage reflection

- extract and evaluate meaning

- applying the learning to future thoughts and deeds.

The National Strategies (Department for Education and Skills (DfES) 2003), which aim to improve the quality of teaching and learning at KS3, illustrates how such learning principles can be translated into lesson planning with starters, challenging activities and plenaries. A historian in Lacon Childe School (see Chapter 4) applied these principles in teaching his students some rudimentary debating skills. An initial phase asked students to recap on their knowledge from a previous lesson about progress resulting from the industrial revolution in Britain. He invited them to debate as two halves of the class and created rules for argument and counter-argument. Students were challenged to use evidence to debate the case. A plenary session asked students to think about how they had tackled the task, to identify appropriate skills and to think how they might find evidence if the debate took place in contemporary Britain.

Doing, reviewing, learning and applying in Citizenship

How to deal with bullying, see Chapter 6.

Figure 1.1 Kolb 1984

Looking for meaning

The focus of learning should involve a search for a deep, rather than a surface, meaning. Students who view learning to be about memorising and reproducing knowledge, tackle a task very differently from those who view learning to be about seeing things in a different way (Marton 1981). Future citizens may have a need to recall information on the spot, but they also need to see issues from different perspectives and begin to examine their own ideas in different ways. Without such education, it is hard to imagine how young citizens would make sense of the reporting of wars and the reasons why governments of some nations send their troops to fight.

Large-scale and small-scale tasks

The national guidelines for Citizenship expect students at the end of KS3 to be able to understand how the public gets its information and how opinions can be formed and expressed. The KS4 programme expects students to understand something of the ways in which political and economic systems work. Good contexts within and across curriculum subjects provide a meaningful framework for important, complex and controversial issues.

The Campaign, an investigation in Chapter 5, illustrates how students move from a classroom-based activity towards a research task focused on the working of local councils and pressure groups. The investigation runs over several lessons and forms a substantial Citizenship unit within the PSHE programme.

In contrast, an English teacher in Christopher Whitehead School, in Chapter 6, succeeds in challenging students to think again about their views of bullying through a role play which is self-contained within one or two subject lessons. Students find much satisfaction in pursuing an issue in detail and with real commitment because that is what they are used to in this lesson. The interpretation of ‘economic and political system’ here is generous because a complex set of decisions and policies is represented by a single issue and involves a limited number of participants.

These lessons differ in scale and ambition but in both cases, the students are helped to transfer their school-based learning to real-life contexts in a meaningful way.

Encouraging a ‘can do’ mentality

Students need to develop a positive view of their achievements and to avoid attributing poor performance to themselves as a kind of character fault. The negative effect of focusing on performance at the expense of learning leaves them feeling helpless (Butler 1998).

In Citizenship students need to be encouraged to:

- have a go

- believe that they can always improve and learn

- take on challenging tasks

- ask lots of questions.

If they believe that they have to be clever before they can tackle a task, and if they feel that they must always appear clever in front of their peers and teachers, they will be less successful learners.

Chapter 5 explains how Rhodesway School in Bradford used The Campaign as a basis for a Citizenship investigation. Some students decided to deal directly with the local mayor on the phone to find out local government plans.

One school asked a technology group to take on a ‘commission’ from a business partner to design decorations for a special Halloween event in a restaurant. The students were not all confident in their own ability to be creative, to manage the process of plastic injection moulding, nor to complete a task in a given time limit. A visit from the restaurant manager provided a real fillip because they were expected to succeed and they realised the business was serious about using their ideas. At the end of a series of lessons involving starts and false starts, two groups presented their finished prototypes and were delighted to receive orders from the business manager. They were less pleased when he asked them to tone down their ideas for scary masks and green-coloured cheese in the interests of keeping his customers. The students’ self-esteem was boosted but an important lesson was learned about researching the needs of a client.

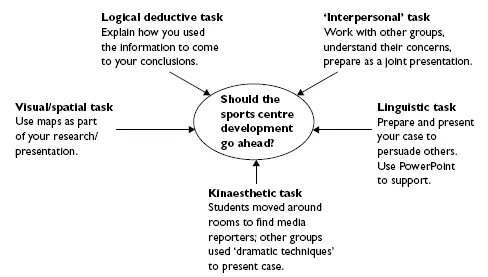

Valuing different kinds of learners

Future citizens will be encountering new ideas in many different ways. In later life they will be valued for their ability to communicate, their sensitivity to others as well as academic qualities. The intelligent learner comes in many different forms and it is important to value their different characteristics. Both multiple intelligences (Gardner 1999) and emotional intelligence (Goleman 1995) have contributed to an understanding of how young people learn and interact (Figure 1.2).

When considering the education of the whole child (Rogers 1961) it is clear that feelings are an important part of the process of learning. Thinking about the affective domain can be as powerful as cognitive development and may be at the heart of a worthwhile Citizenship activity.

Figure 1.2

In one school assembly, a visiting representative from Christian Aid expressed his anger at the apparent arrogance of some people who assumed they were solving all the problems of ‘deprived’ families in Africa by making financial donations. The strong emotions on show generated much debate in the school where regular collections for charities were an assumed part of life. Students began to ask questions about what money was collected, for whom and why.

In another school, Year 7 students were asked about the progress they thought they had made in the development of Citizenship skills in the past year. Several students described how a group of girls had provided brilliant support for other students who were worried about bullying, about their lack of confidence and about their own personal relationships. The girls’ interactive skills were highly prized by students and their views have encouraged school governors and staff to review the provision of counselling and welfare support in the school.

In Chapter 6, it is clear that the impact of a role play on the participants was strengthened by the commitment and feelings expressed about bullying. While teachers have to exercise care in managing the activity and ensure that the students are helped out of role at the end of the lesson, the experience is likely to stay in students’ minds for a long time. It may also help students to transfer their learning from school to home where serious issues are discussed. Feelings often run high in such situations and it is important that students can manage to mix passion with more measured argument.

Learning together

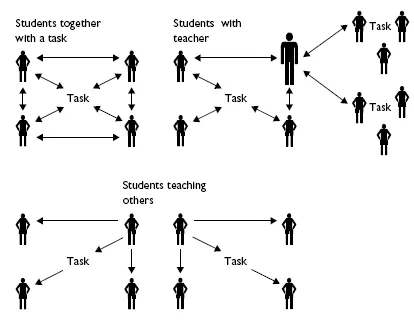

It is hard to imagine how any young citizen could learn effectively about rights and responsibilities alone with just a book and a quiet room. Social interaction makes an important contribution to good learning (Bruner 1996; Vygotsky 1978). A school setting is an obvious place where students can test out their understanding of what it means to take responsibility for their behaviour and that of others. They can voice different ideas about rights and wrongs and learn that their perspectives on life may be different to those of others around them (Figure 1.3).

Group activity is a feature of many Citizenship activities and as is evident at the Ridgeway School (see Chapter 11), students can be effective co-teachers as well as co-learners. Students as well as teachers can help learners to discover or understand ideas in a way that was just beyond them as individuals (Vygotsky 1978). The insight provided by students to the class at Ridgeway School led them to look at the situation in a very different way. One teacher can have an impact on the thinking of a whole class but students as teachers can orchestrate as effective an impact in a different way within a small group or whole class activity.

Talking constructively

The unpredictable nature of discussion and of students’ behaviour can be a worry to teachers unused to managing lessons based on a lot of interaction among students. Carefully constructed simulations are one solution because they can lead students to discuss sensitive issues in a way which can be managed successfully while still giving room for personal expression. In Chapter 9, President for a Day helps students to understand the issues relating to economic development in an African country. They are presented with contradictory evidence for different decisions and therefore have to evaluate and come to conclusions themselves.

Figure 1.3

Students’ communication skills lie at the heart of social interaction and Chapter 3 illustrates the importance of discuss...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Reflective teaching, reflective learning

- Chapter 2: Reflective teaching and controversial issues

- Chapter 3: Developing discussion

- Chapter 4: Thinking through debate

- Chapter 5: Investigating Citizenship

- Chapter 6: Role play: Using perspectives

- Chapter 7: Group work: Strategies and outcomes

- Chapter 8: Thoughtful presentations

- Chapter 9: Learning with simulations

- Chapter 10: Informing and communicating with technology

- Chapter 11: Participation in Citizenship

- Chapter 12: Citizenship and the whole school

- References