This is a test

- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Using historical evidence as well as personal accounts, Tracy C. Davis examines the reality of conditions for `ordinary' actresses, their working environments, employment patterns and the reasons why acting continued to be such a popular, though insecure, profession. Firmly grounded in Marxist and feminist theory she looks at representations of women on stage, and the meanings associated with and generated by them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Actresses as Working Women by Tracy C. Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE PROFESSION

1

THE SOCIOECONOMIC

ORGANIZATION OF THE

THEATRE

Victorian performers were an unusual socioeconomic group. Unlike other professionals, they were recruited from all classes of society.1 While performers repeatedly demonstrated that class origins could be defied by hard work, talent, or strategic marital alliances to secure some a place in the most select company, others lived with and like the most impoverished classes. Unlike other occupational groups, performers' incomes spanned the highest upper middle-class salary and the lowest working class wage, and were earned in work places that ranged in status from patent theatres to penny saloons. The heterogeneity of performers' experience, competence, salaries, and social classes made them anomalous among middle-class professionals, while the differences between their art and others' trades set them apart socially and existentially from the people of the factory, mill, and workshop. In a sense, they were everywhere and nowhere in Victorian culture, only nominally classifiable as a group, and as diverse as possible in their rank in the social pecking order.

Actresses' identity within this occupational cluster was further complicated by social constructs of their sex. All Victorian women's lives were interpreted by a male-dominated culture that defined normative rules for female sexuality, activity, and intellect. Social respectability was merited as long as women met the views prescribed for their age and class, but actresses—virtually by definition—lived and worked beyond the boundaries of propriety. Victorians were deeply suspicious of women whose livelihood depended on skills of deception and dissembling, and the circumstances of actresses' work belied any pretences to sexual naïveté, middle-class immobility, or feeble brain power.2

In his history of the Victorian acting profession, Michael Baker argues that the increased respectability of the theatre as a social institution of entertainment and culture coincided with the inclusion of acting among the professions. Educated, self-regulating, and respectable entertainers were accepted as the heart and brains of the leisure industry, resulting in what Baker calls the ‘rise of the Victorian actor’ to a middle-class status.3 Baker's argument rests only on information about the most successful performers in legitimate lines of business (especially serious drama and comedy) based in the West End of London. The circumstances of the majority (including performers who were lower paid, non-legitimate, provincial, or female) are almost entirely left out of the equation. Baker dates the transcendence of (highly paid, legitimate, successful, male, West End) performers to 1883, the year that Henry Irving declined Gladstone's offer of a knighthood. Irving's subsequent behaviour and his colleagues' recognition of him in the 1880s and 90s as their foremost artistic, social, and political representative does make it appear as if the honour had been accepted, or that it was a fait accompli in all but the ceremony. But Irving did not accept the honour until 1895. Whatever the first and second offers of this knighthood signify about performers' status, a distinction between West End stars and the rest of the less privileged ranks remained marked long after Irving arose ‘Sir Henry’.

Following the bestowal of Irving's knighthood, performers revelled in public acknowledgment of their long struggle for recognition as respectable, responsible citizens on a par with what the census designated as ‘Class A’ professionals (barristers, physicians, the military, and the clergy). A string of knighthoods to male West End actor-managers specializing in legitimate theatre followed: Squire Bancroft (1897), Charles Wyndham (1902), Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1907), and George Alexander (1911).4 It is significant, however, that the first female to be thus honoured for service to the theatre (rather than raised to the honour through marriage) was Geneviève Ward, appointed D.B.E. in 1921.

Almost no actress maintained as strict standards of propriety throughout a long career as Ward. Although she managed her own company for years and enjoyed international admiration and respect, a quarter of a century elapsed between the first such recognition of the lifetime contributions of an outstanding, upright actor-manager and the granting of an equivalent honour to an outstanding, upright actress-manager. A fundamental distinction was made between Irving and Ward, and the distinction was based on gender. True, Irving was a sort of ambassador of the theatre, but so was his leading lady Ellen Terry, who received her D.B.E. thirty years later (or forty-two years after Irving's first offer of a knighthood). Terry had been the most popular and universally revered English actress of her time. She had also mothered two illegitimate children and had several marriages and numerous affairs with notable men, including, by popular rumour, the impeccable Henry Irving. Of course, by 1925, Terry had long since gone into retirement and the public that applauded her and Ward in their prime was not that which lived to call them ‘Dame’. Terry's D.B.E. followed closely upon Ward's;5 evidently, the social gulf that distinguished the daughter of itinerant players and enchanting mistress of artists and actors from the Countess de Guerbel (daughter of a scion of New York City) was at last bridged. Until the 1920s, women were prevented by their collective social status and stigmatization by the educated classes from due recognition. Similar factors prevented Charles Kean from being officially recognized for his services to the Queen in the mid-nineteenth century.6 As long as the public regarded the theatre (or an employment subcategory within it) purely as a source of entertainment and did not take it seriously as a educative moral forum operating for the general good, performers were denied the appreciation granted to architects, sculptors, painters, and musicians.

Becoming a member of the ‘actressocracy’ is in no way equatable to being knighted.7 Anastasia Robinson and Lavinia Fenton gained fortunes by wedding Charles Mordaunt (the Earl of Peterborough) and 3rd Duke of Bolton respectively, but their marriages were not sanctioned. Elizabeth Farren, Louisa Brunton, Mary Bolton, Maria Foote, Katharine Stevens, Harriett Mellon, Connie Gilchrist, Valerie Reece, and Belle Binton were socially recognized after marrying into the peerage, but permanently forfeited their careers. Irving, Bancroft, Wyndham, and Tree, in contrast, added a title which augmented their prestige in society, while continuing to do what made them meritorious. When actresses married titled gentry, their prestige and allure as performers was no longer relevant because they retired from the stage; when men received knighthoods in their own right, however, they used this official status to enhance their professional cachet, and became better box office draws than ever. Whereas the women exchanged a public life for a private life (albeit celebrated), the men became more public figures than ever, representing their profession to society. While Victorians could reason that the ‘actressocrats’ were chosen for an honour by one individual (who, in his crazed enamour, may have been blind to the significance of the woman's station or have been devoid of good judgment and taste), it was indisputable that the men were recognized by the monarch in her capacity as a representative of the government and all the people, and warranted general acclaim.

The social operation of gender distinctions is as apparent in the bestowal of criticism as it is with honours. The respectability of actresses was assessed on different terms from that of actors, though after Irving's knighthood it was less acceptable to say so. Victorians' failure (and perhaps refusal) to acknowledge actresses' respectability results from their defiance of socioeconomic prescriptions about genderized social roles and working spheres for ‘Good Women’. Certain realms of artistic production changed significantly before Irving's career began, making possible the visually and contextually genteel accomplishments of Irving, Wyndham, Tree, and Alexander. In other realms—particularly burlesque, extravaganza, ballet, pantomime, and music hall, where women's employment was concentrated—the social stigma on female performers was perpetuated by the context in which they were presented on stage. The neighbourhoods of playhouses, costuming, and customary gestural language of the non-legitimate stage perpetuated and reinforced the traditional view of actresses. Performance genres (once they were established) changed little and reinforced rather than challenged the sexual and gender stereotypes. The circumstances of women's work conspired with socioeconomic circumstances to prevent women performers' ‘rise’ to social or cultural transcendence.

FAMILY DYNASTIES, RECRUITMENT, AND CAREER OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN

The free trade in spoken drama (dating from the Theatre Regulation Act of 1843) took control of the theatrical industry from the hands of a few and made licences available to unlimited numbers of small and large scale entrepreneurial managers. The greater number of managements and theatres meant greater mobility of labour, a more economically competitive marketplace, and wider employment opportunities for performers. With the introduction of long runs in the 1860s came a gradual change in the nature of engagements from seasonal salaried contracts for all players to run-of-the-piece contracts for most players and waged weekly employment for players in the smallest roles. The eighteenth-century stock system dissolved in favour of companies producing single pieces, sometimes touring as number one, two, and three companies with the same piece under a single controlling management, or less often as self-contained repertory companies with two or three plays and a star. Acting style, training opportunities, and recruitment were all affected. Performers' career opportunities, which had previously tended to be focused on a provincial circuit or a particular London theatre, were decentralized and could change many times in a single year. Career pathways multiplied but the constancy of touring, the fluidity of the acting community in touring companies, and the ferocious competition for employment had an even greater effect on theatrical women than on men because of the implications for restricted variety in casting, disruptions to family life, and the premium on ties to a management giving steady employment.8

The localizing of the theatre community in seventeenth-century Southwark and Shoreditch, and eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Drury Lane (plus selected provincial cities) broke down in the Victorian period as the entertainment industry reached out to all corners of the nation and became as much a feature of neighbourhoods and small towns as it had previously been of large or market cities. Concentration of power in theatre-owning managerial families was challenged as more and more novices came from non-theatrical backgrounds and rose to managerial status. The erosion of family control of management and hiring expedited the opening of theatres to recruits from all sorts of backgrounds. As long as nepotism was the basis of hiring and promotion, actresses enjoyed the advantages of physical and financial security within the family compact; later, Victorian actresses from increasingly heterogeneous backgrounds were faced with the necessity of negotiating their own terms of employment, fending off unwelcome sexual advances themselves, and learning to compensate for being barred from the back rooms and club rooms of male acting society.9

Unlike the ‘true’ professions, the stage had no standardized system of examinations or qualifications, yet it was grouped on the census with the Order III professions: the clergy; barristers, officers of the courts, and law stationers; physicians, druggists, and midwives; authors and editors; artists; musicians and music teachers; schoolteachers; and engineers and scientists. These are distinct in the Victorian hierarchy from the military and civil service in Orders I and II. The census is a mine field of taxonomic peculiarities, and critiques of enumerators' failure to record women's occupations accurately (or to record them at all) are justified,10 yet in the permanent absence of other comprehensive comparative data the published census is worth consideration. It shows a field into which women entered in great numbers between 1841 and 1911, equalling and then eclipsing the number of their male colleagues, despite a concurrent influx of men. Particularly in the latter period, when the spectacular increases in the acting population are more evenly shared by the sexes, it is important to read the figures in relation to three factors: (1) the influx of women into other professional groups, (2) the overall rise in population, and (3) the theatrical population in the major industrial cities.

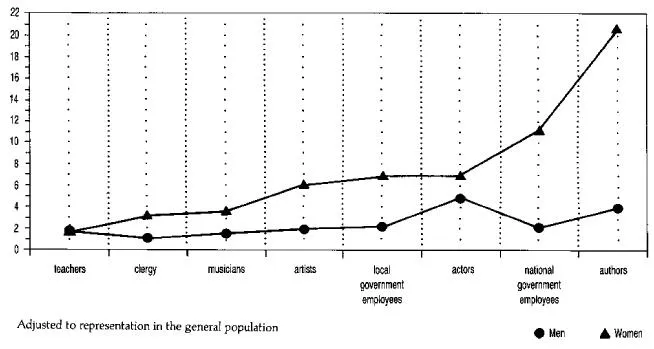

Figure 1 Multiples of increase in selected professional groups, England and Wales 1861-1911

Charting the accumulated fifty year multiples of increase into national government, local government, writing, fine art, music, acting, and teaching reveals that the theatre underwent comparatively little change in its sex ratio, second only in consistency to the teaching profession (Figure 1). The literary profession was the most affected by women's influx—more than twenty fold (X20.72)—with the national civil service next in line (X11.29). Acting had the greatest increase among men (X4.96), well above the male mean increase of X1.96; the increase of actresses is significantly greater (X7.09), though this falls below the women's mean of X9.55. Actresses' statistical growth is best compared to musicians' and music teachers' (X3.56 overall), especially when the sex ratio is involved:

| Acting | Music | ||

| (Female:Male) | (Female:Male) | ||

| 1861 | 67.96:100 | 56.92:100 | |

| 1911 | 101.05:100 | 96.32:100 | |

Several factors slowed the increase of women musicians: certain instruments were ‘off bounds’ to women; until a woman virtuoso (such as Marie Hall) emerged on a particular instrument women's capacity for mastery was doubted; and women were barred from most professional orchestras (including theatres) and ghettoized in ‘minor’ performance types such as l...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE PROFESSION

- PART II: CONDITIONS OF WORK

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY