eBook - ePub

Innovation in Architecture

A Path to the Future

This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Innovation in Architecture

A Path to the Future

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this highly original book, through a series of essays, key architects and engineers in Europe, Australia, and the USA describe the ideas and development behind the innovative technology in their chosen projects, with the emphasis being on the means of production and the links between design and the manufacturing process.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Innovation in Architecture by Alan J. Brookes, Dominique Poole, Alan J. Brookes, Dominique Poole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Alan J.Brookes and Dominique Poole

The doctor can bury his mistakes but an architect can only advise his clients to plant vines.

Frank Lloyd Wright, New York Times Magazine, 4 October 1953

The dictionary definition of ‘innovate’ is to introduce new things or methods into established practice. Invention can be considered as the process of discovering or creating a novel idea, while innovation is the application or exploitation of an idea. Innovation also differs from invention in being achieved through a deliberate application of knowledge.

The issues relating to innovations in new materials and the technology utilized in their application are complex. Innovations in building materiais are by no means a simple process. Marian Bowley describes a process consisting of three main stages.1 Initially the new material is invented or introduced. This is followed by a period in which use becomes established, which may include changes to improve performance. Finally different varieties of the original material may be developed. This book mainly includes examples where architects and engineers have introduced innovation as part of their bespoke designs for a building project.

Jean Prouvé has discussed a deficiency of architectural inspiration in relation to the new materials that mechanization has put at our disposal. He suggests that this is partly due to a lack of courage, a quality fundamental to a change in attitudes towards innovation in design. He was not alone in this observation. More recently Peter Rice has written of courage as the missing ingredient in the process of design development:

The courage you need is the courage to start. Once launched, then each step can be evolved naturally. Each step requires careful examination. The courage to start and an unshakeable belief in one’s ability to solve the new problems which will arise in the development are essential.2

The various contributors to this book have shown in their own work their willingness to be involved in this innovative process and to face the risks involved.

The idea for the book stemmed from research into innovation at Oxford Brookes University leading to Dominique Poole’s PhD thesis. Some of the contributors were present at a conference at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago in 1999, organized by Professor Peter Land, at which delegates were invited to show their work in a critical way—exhibiting not just the end result but also the difficult process by which they achieved their aims—and to compare new ways of dealing with materials and building techniques. The book has therefore concentrated on the exploration and development of the ideas driving architectural solutions rather than on an appraisal of the end results and it is assumed that the reader will already be familiar with most of the projects described by the various authors.

Perhaps we should first investigate why architects and engineers use materials in an innovative manner and produce innovative structural solutions. They may simply be responding to the opportunities offered by new materials and the more sophisticated means of prediction now available to them. Alternatively, it may be, as Martin Pawley argues, that architects have lost their ability to control traditional technology and that control can only be regained by recognizing and transferring advanced techniques from other industries to architecture.3

There may be additional sources for technological change. Nature has always had a profound influence on architecture in both aesthetic and functional terms. For centuries people have looked to nature for an understanding of process or indeed for inspiration. Peter Buchanan has written about the natural influence behind Renzo Piano’s Menil Museum.

For architecture or technology to emulate nature neither necessitates nor excludes using natural materials and vernacular, or biomorphic forms. But as science unravels nature’s secrets, it is the leading edge of technology, which some may mistake for its most artificial and unnatural pole, that is most likely faithfully to appropriate nature, especially in artefacts expressly created for some high performance application. This artefact or component may have biomorphic form, not because it is styled that way, but because it happens to offer the economy, efficiency and exact fit for purpose found in organic creation.4

In learning from nature the ultimate goal is an architecture that responds to the environment. David Kirkland, Marks Barfield, Eva Jiricna and Volkwin Marg (Chapters 4, 6, 9 and 12) all refer to their interest in scientific discovery and the influence of forms in nature.

An idea often promoted within architecture is that of technology transfer, where a vast technology exists outside the construction industry and the architect acts as ‘active forager’, as bridgehead or a technologytransfer mechanism from these other sectors. This is not necessarily the case, however. Our belief is that technology actively exists within the present building industry. This resource is playing a more significant part in modern architecture as a result of a change in attitudes towards construction and its effect on design. This idea is reinforced by Professor Beukers of the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering at Delft University of Technology, who believes that the aerospace industry is relatively conservative compared to the British building industry and indeed looks to us for a sense of innovation.5

Many of this book’s contributors admit to an early interest in the mechanisms of how things are put together. Volkwin Marg (Chapter 12) refers to his childhood in Danzig, where he had a keen interest in boats and the natural materials used in their construction. Tony Hunt (Chapter 3) describes how he was brought up on Meccano and became fascinated by powered model aircraft design while still at school. Mike Davies’ amusing description (Chapter 2) of his time at the Architectural Association, his interest in pneumatics and the influence of his tutor, Ron Herron (Archigram), shows his early interest in alternative technology.

Peter Rice, in his book, An engineer imagines, comments:

Exploration and innovation are the keys. I have noticed over the years that the most effective use of materials is often achieved when they are being explored and used for the first time. The designer does not feel inhibited by precedent.

1.1 Natural forms: the spider’s web

Modern building with innovative forms and use of materials offers this opportunity for exploration. Each building is in effect a prototype and the building industry demands its particular method of design, testing and sourcing of materials.

Extreme environments may also act as a catalyst for innovation. Much in the way of new technology and materials used in construction was originally developed within the aerospace industry or by NASA, who are skilled in experimentation within extreme environments. The United States proposal to build a space station in the 1980s led to a research programme in deployable structures funded by NASA.6 Richard Horden (Chapter 8) is clearly influenced by his knowledge of alternative technologies and by his work as Professor of Architecture in Munich on crew habitation units for NASA.

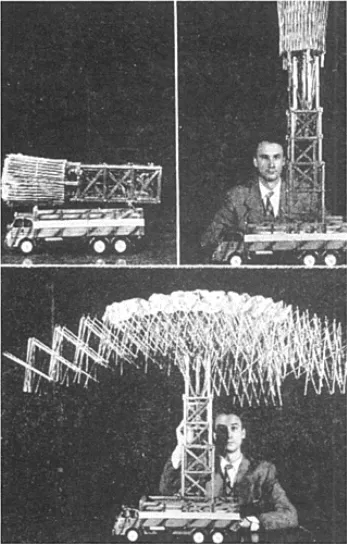

1.2 Deployable systems may be developed through origami and mathematics

The introduction of these unfamiliar technologies raises the issue of risk and the consequential professional indemnity requirements. Architects generally accept a responsibility to their client and may be reluctant to utilize a new technique until evidence exists to support its success. Thus a critical consideration behind the ability to innovate is the available capacity to design, prototype and test. Only through these means is confidence in a new product or method of construction established. Architects keen to explore frontiers of design and innovation are forced to carry out experimental models, often at their own expense, to prove their ideas will work in practice.

Generally, in any other manufacturing industry, the first project utilizing a new method of construction or application of a new material would be seen as a prototype. However, buildings by their nature are often intended for longevity of use so defects and long-term durability are determined only after significant time has passed. British standards and codes can be used as a datum point for established materials, but such guides are unlikely to be available for new methods, furthering the level of risk involved. Additionally, architects are often required to work to tight schedules and these may simply not allow for an exploration of an innovative method, forcing them to make do with an established material or method of construction. Quantity surveyors’ costing methods are also based on tried and tested solutions, where general judgements are based on past experience and knowledge.

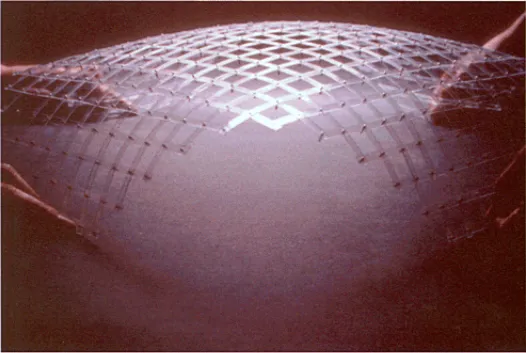

1.3 Computers and models extensively simulate practical circumstances: experimental model of an aluminium grid shell (architect: Brookes Stacey Randall, 1993)

In order to design within a new process it is important for the architect or engineer to know the limitations of that process. In the development of the Pompidou gerberettes the design team made visits to foundries to gain a better insight into the limitations of cast steel. As Peter Rice explains,

When innovating, which using cast steel in this way was, it is essential to have detailed and thorough analysis facilities available from highly skilled people with no emotional commitment to making the solution work, just a clear, logical and objective insistence that the structure and its materials satisfy all the laws and requirements they should.

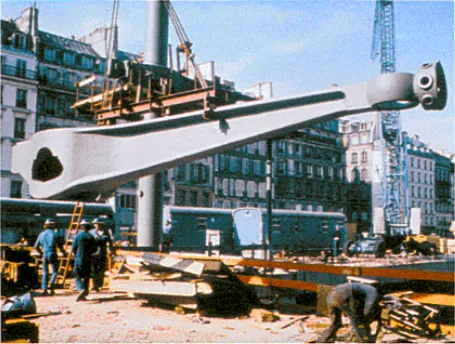

Cast steel was a poorly understood material, having a craft-based background dating from the nineteenth century that had failed to evolve. This prompted a new technology to be introduced in order to test the pieces successfully. At the time, fracture mechanics was emerging in other industries, prompted by the need for reliable steel jackets for nuclear reactors and by the complexity of constructing oil platforms for the North Sea. Fracture mechanics is the science of predicting the behaviour of metals under strain and how they would react if small flaws and cracks existed within them. The Pompidou team were able to benefit from this knowledge to cast the gerberettes—an example of technology transfer, where an existing technology from one industry is utilized within another. Although this was the process through which the gerberettes were finally produced, the marriage of a traditional craft process and the innovative method of fracture mechanics did not initially prove successful because of a failure in communication.

1.4 The Pompidou ‘gerberettes’ being hoisted into position (architect: Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano)

In a similar way Eva Jiricna (Chapter 9) describes how the slight difference in size between Czech and British metric screws nearly caused a failure in the construction of her Orangery in Prague. Eva is renowned for her ability to utilize glass as a construction material but remains pessimistic about the prospects for advanced technology, as the cost of tooling up new components can never be covered by the return on any single project. On the subject of the glass staircase for her client Joseph Ettedgui she says: ‘We use it as a structural material: not placed on top of something as a surface but as a replacement for metal or wood. It is only possible because there are no faults in glass: it’s very homogenous.’ Interestingly, the first edition of New ways of building by Eric de Mare contains an illustration of glass stairs dating from 1937. They form the entrance of the St Gobain Glass Pavilion of the Paris Exhibition.7

The projects reviewed in this book show there has been a considerable increase in the use of new materi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Picture Credits

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Exploring, Rehearsing, Delivering

- 3. Concept Before Calculation

- 4. A Process-Oriented Architecture

- 5. Material Innovation and the Development of Form

- 6. More than Architecture: David Marks and Julia Barfield

- 7. An Engineer’s Perspective

- 8. Touch the Earth Lightly: Richard Horden

- 9. Production Processes, sources and uses of Materials: Eva Jiricna

- 10. Constructing the Ephemeral—Innovation in the use of Glass

- 11. The Tradition of the Primitive with Modern Materials—an Australian Perspective

- 12. A Passion for Building: Volkwin Marg

- 13. The Incredible Lightness of Being