![]() Part One

Part One

The Elements of Reporting![]()

Chapter 1

Connecting the DOT

Finding stories that matter and reporting them with impact should be the primary goals of any journalist. But good intentions will not make you a good reporter. You need to know the essential tools that top-notch journalists use to gather information, applying them in a structured way to produce articles with high credibility. This chapter will introduce you to a methodology for news reporting based on analyzing documents, making observations and talking to sources. It will then describe how that methodology works by integrating the information that you uncover in a way that will help you produce compelling stories, whether you are working on a routine assignment or a major project.

Bob Woodward, whose work on the Watergate investigation led to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon, has won nearly every major award in American journalism and been described by his contemporaries as one of the best reporters of all time. But shortly after he started working at The Washington Post in 1971, he came perilously close to making the kind of mistake that would have made his editors doubt his reliability and might well have kept him off the Watergate story.

Woodward is legendary for his ability to develop and work human sources, and after just a few months at the paper he had found one at the District of Columbia Department of Health who was funneling him copies of restaurant inspections. One day the source came through with the makings of a sure-thing Page 1 story: extreme sanitary violations at a place that Woodward instantly recognized as a landmark dining establishment for Washington’s elite: the Mayflower Coffee Shop.

As Woodward recounts in a video interview posted on YouTube (Woodward, 2009), the Mayflower is a storied establishment just a few blocks from the Post and not far from the White House. For decades it enjoyed a reputation as the finest hotel in Washington, the site of gala events for celebrities and political leaders as well as private meetings among lobbyists, journalists, industrialists and all manner of movers-and-shakers.

The tip that Woodward had received was a journalist’s dream—an airtight story that was based on solid documentary evidence that could be easily buttressed with quotations drawn from on-the-record interviews. Without leaving his chair, he was able to write up a sensational story (both in the sense of very good and in the sense of impossible to ignore) using the two strongest and most reliable methods of information gathering: analyzing documents and interviewing sources. As an added bonus for his editors, the story was so neatly laid out for him that Woodward was able to finish his article long before the deadline for the next day’s paper.

A Rookie Mistake—Averted

Lucky for Woodward, one of his editors insisted that he not take the rest of the day off as a reward for his efforts but instead employ the gift of time to make use of the third of what Woodward describes as the three “channels” that bring the news to a reporter: direct observation. Dutifully Woodward set off down 16th Street toward the Mayflower and started making inquiries. Much to his surprise he learned that there was no Mayflower Coffee Shop at the Mayflower Hotel. He took a look back at the inspection report and noticed that the address of the Mayflower Coffee Shop was farther north, at another famous Washington hotel, the Statler-Hilton. He made his way there and came upon a prominent “closed for repairs” sign at the Statler’s eatery. Looking around, he found a restaurant manager and confirmed with him that the repairs that were being made were indeed at the behest of the Department of Health to address violations of the city’s sanitation code.

Woodward quickly returned to the Post’s newsroom and asked for his story back, telling his editor that he had “a few minor corrections” to make. The moral of the story, Woodward says, is that a reporter cannot rely on just one or two of the news gathering tools. His use of documents and interviews had gotten him a Page 1 story, but “without me … going to the scene we probably would have had to run a front page correction also,” Woodward recalls.

Looking back, decades after that incident, Woodward can clearly describe how journalists use three basic tools of reporting in a process of triangulation—taking information that arrives in one form and checking it against information that arrives in other ways. But this process wasn’t written down somewhere for him to read and absorb. Woodward had a savvy editor who made him keep reporting even after he thought he had finished his story. But not all rookie reporters can expect to get the same treatment as they learn the ropes. In many of today’s newsrooms, the ranks of editors have been thinned, and the ones who are left have taken on more duties, leaving them little time to pass on their years of wisdom to those who are just starting out. Given the accelerating pace of the 24-hour-a-day news cycle, reporters with little experience will likely find themselves on their own as they climb a steep learning curve for how to cover the news.

A Roadmap for Reporters

That’s why this book was written: to provide a roadmap and a methodology that journalists, or people who want to be journalists, can use to find the stories that matter and report them in a way that has an impact on readers. In today’s competitive environment, journalists can’t afford to waste any time. They need to move quickly to stay ahead of the news, and when a story breaks, they need to know how to go about gathering information so that they can provide comprehensive and authoritative coverage.

To help students meet this challenge, this book focuses on the three specific tasks that, according to Canadian journalism scholar G. Stuart Adam, are at the core of a reporter’s pursuit of authoritative facts: “acts of observation, analysis of documents and interviewing” (Adam, 2006, 357). Whether consciously or not, the best reporters use these three tools in a way that allows them to cross-check and authenticate facts, to reduce or eliminate unsupportable allegations, and to lead them to a deeper level of insight and understanding. The topflight journalists may use these tools with greater sophistication and efficiency than less experienced colleagues, but they are exactly the same tools that are available both to the Pulitzer Prize winner and to the rookie reporter assembling an overnight police roundup based on blotter entries, questions posed to the department’s press officer and, when time allows and circumstances warrant, a visit to the scene of a crime.

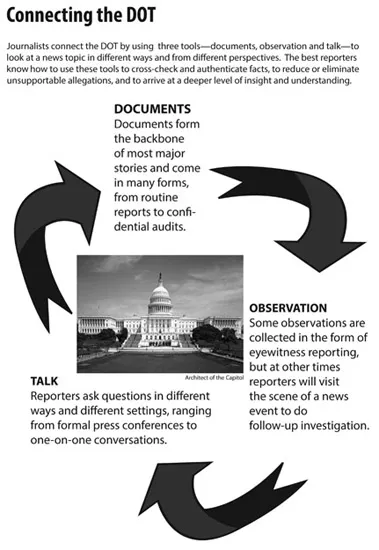

For lack of a better term, and at the risk of appearing glib, the methodology in this book is called “Connecting the DOT” (see Figure 1.1). The first two letters of this acronym come from two of the three elements, documentary analysis and observations made in the field. The acronym is completed by substituting the word “talking” for “interviewing.” This switch accomplishes two things: It creates an easy to remember term, and it underscores the fact that when it comes to getting information from human sources, there are alternatives to the question-based interview approach that may lead to better results. But it’s really the first word in the phrase, “connecting,” that is most significant. It is meant to underscore a way of approaching the news that is based on a mindful comparison of facts and purported facts as a way of getting closer to a true account of events. Rather than pretending to be a mere conveyor of information, a reporter who is connecting with the news in this way is using a “not quite scientific” method based on testing and retesting theories and suppositions with the evidence that is provided through documents, observation and talk.

FIGURE 1.1 Diagram depicting the process of “Connecting the DOT.” Credit: Miles Maguire

A Flexible Methodology

In the following chapters, you will learn more details about each of the core activities of DOT. Subsequent chapters show how to work with DOT tools from the first day of the semester on simple assignments, such as a weather story, and then how to expand your use of these tools as you progress to more complex articles. As you learn to “connect” the information you have gathered, you will also start to explore the more subtle aspects of reporting, including situations that present ethical concerns, defenses that can be used to deal with propaganda and public relations, and the challenges of pursuing stories that may upset well-connected people, powerful institutions or deeply held community values.

One reason why journalists may not consciously think about using documents, observation and talk as a unified methodology is the way that the practice of reporting has evolved. Sociologist Michael Schudson describes how reporting before the Civil War was largely a matter of “stenography, observations, and sketches” (2008, 81). In the second half of the 19th century, a second technique was added: interviewing, which helped to identify “journalism as a distinct occupation,” according to Schudson. Just as interviewing was not widely accepted as a legitimate journalistic tool initially, the profession took some time to overcome its concerns about documents. Curtis D. MacDougall’s seminal 1938 textbook, Interpretative Reporting, places far greater weight on cultivating human sources than on consulting documents and even warns about the dangers posed by relying on careless writing often found in a police blotter. But the central role of documentary analysis, as opposed to the mere reprinting of official notices, was well established by the end of World War II and exemplified in the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting that James Reston won for his coverage of the Dumbarton Oaks conference. Reston’s key scoop explained the negotiating positions of the major world powers as they discussed the formation of what would become the United Nations. Reston explains in his memoirs that this story came about because a source, who was Chinese, “opened up a big briefcase and handed me the whole prize, neatly translated into English” (1991, 134).

Whether they are writing for print, lining up interview subjects for a news broadcast or developing multimedia packages for the Web, professional journalists are aware that all reporting is ultimately based on a narrow set of activities that are performed, to varying degrees, in just about every assignment. These three reporting tools—documents, observation and talk—do in fact represent a widely used methodology, although they are not acknowledged as such. This book’s conception of DOT as a methodology goes a step further, showing how the three tools are most successful when used dynamically, not as individual reporting techniques but as part of a unified approach that seeks out contradictions and makes plain the places where fact-gathering has come up short.

How News Comes to be Known

Each element of DOT represents its own way of knowing, what philosophers call “epistemology,” and each comes with intrinsic strengths and weaknesses. Documents, assuming that they are based on the work of fair-minded and disinterested researchers, reflect an accumulation of knowledge, but they provide no guarantee of accuracy and may embody hidden or unconscious bias. Information gained through firsthand experience has the benefits of immediacy and authenticity, but it is also limited, in no small part because of its specificity of perspective. Talk with human sources can lead to colorful details and unexpected insights, but verbal communication is fraught with the possibility of misunderstanding and omission. As reporters gain experience with these tools, they also learn about their limitations as well as their ability to function iteratively. A document may contain names that lead to human sources; an interview may inspire a site visit to inspect a particular locale; as part of an observation, a reporter may meet additional sources, who may in turn provoke additional documentary research. Ultimately, however, these reporting tools require different underlying skills and appeal to different personality types. That’s why many reporters specialize in one kind of reporting and why the three elements of DOT are rarely viewed as a holistic methodology.

The Difficulty of Documents

Documents, for example, can be dull, difficult to get and hard to understand. For those three reasons, some professional journalists shun the idea of using documents in their research. They think that documents are just too time-consuming and too much work. But many of the most accomplished journalists, including those with a string of major prizes to their names, have made documents central to the way they work (see Figure 1.2). At the same time, it must be acknowledged that documents are not always reliable and may not even be true.

FIGURE 1.2 The documents that reporters use come in many different forms, including government studies and reports. Credit: Miles Maguire

Documents come in many forms, everything from incident reports filed by police officers to email messages, classified reports, audits, photographs, databases, books and newspaper articles. A good definition of a document comes from William C. Gaines, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the Chicago Tribune who went on to become a journalism professor at the University of Illinois: “A document is information that is preserved” (2007, 24). Using this broad definition, we can see that documents do not have to be on paper or even in a traditional medium. As Gaines puts it, “The document could be written in stone—like a tombstone or a cornerstone of a building. It could be a dental chart or a flag. The contents are the document.” It could also be a voice or video recording.

For starters, here are three reasons why documents deserve so much attention. The most important is that documents are authoritative. As pioneering investigative reporter Paul N. Williams has noted, “Documents are often the best evidence—far better than prejudiced recollections or oral accounts—of what happened” (1978, 37). The second key argument in favor of using documents is that they stick to their story. What’s written on the page doesn’t shift over time, in contrast to what human sources say, or even what a reporter remembers from observations. Sources may want to revise their quotes, perhaps because of pressure from another party or simply because of further self-reflection. This can cause a great dilemma for a reporter—which version of events is the right one to use? The one that provides a colorful, if misleading, story? Or the one that may be closer to the truth but may also reflect a desire to keep embarrassing information out of print? The document, by contrast, keeps stating the same information again and again.

A third reason to emphasize documents is that at least some of them will form a very effective deterrent against libel suits. A document can bolster a reporter’s claim that what was published was true, which has been an absolute defense against libel accusations under U.S. law (Pember and Calvert, 2010). In addition, official police arrest records or transcripts of court testimony are considered by the American legal system to be privileged, meaning that they can be quoted, as long as they are quoted accurately, in news stories. Even if the information in these privileged documents turns out to be false, its origin as an official government statement serves as a shield against libel. While many of the most commonly used documents can provide journalists with this peace of mind, it’s important to remember that it does not apply to all kinds of documents, particularly private correspondence that turns out to be a forgery.

Firsthand Observations

Unlike documents, which at least in theory provide the same information to all comers, observations are highly individualistic and depend on a range of factors, including vantage point and the skill of the observer. For a reporter, the act of observation serves at least two purposes. First of all, the reporter wants to gain as complete an understanding as possible of a story or situation, and second the reporter is gathering specifics that can be incorporated into a news article. In the end these two goals come together as the reporter seeks to strengthen the credibility of a finished account by demonstrating an authoritative understanding buttressed with compelling visual images and other physical details.

It is certainly true that many stories, particularly breaking stories, have to be report...