This is a test

- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

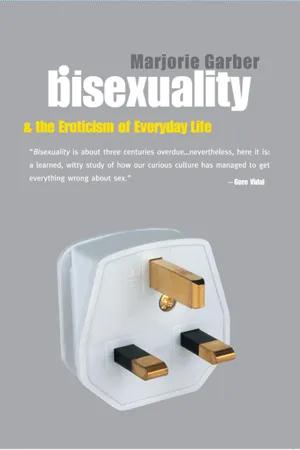

Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

" Bisexuality is about three centuries overdue... nevertheless, here it is: a learned, witty study of how our curious culture has managed to get everything wrong about sex."

-Gore Vidal

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life by Marjorie Garber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

P a r t 1 B i Ways

Culture, Politics, History

C h a p t e r 1

Bi Words

Lots of people think that bisexual means cowardly lesbian.

—The Advocate, interview with Sandra Bernhard’2

Homosexuality was invented by a straight world dealing with its own bisexuality.

—Kate Millett, Flying2

Switch-hitter. Swings both ways. Fence-sitter. AC/DC. These and other once-colorful epithets have been frequently used to describe bisexuality in this century. Whether taken from baseball or from electricity, such terms suggest versatility: a batter who switch-hits often has a better chance of getting to first base—another phrase that has taken on a distinctly sexual tinge in modern times. The New Dictionary of American Slang is more specific than any teenager of my adolescence: to “get to first base” involves hugging, kissing, caressing, and so on; to “get to third base” means “touching and toying with the genitals”; and to “get to home plate,” or to “score,” means “to do the sex act”2—assuming, it seems, that there is only one “real” sex act to do.

Switch-hitters, I remember from my days as a Mickey Mantle fan, were as often made as born. To learn to “swing both ways” meant practice and discipline, not just natural talent. Certainly there was nothing suspect about them; they represented a double strength because they maximized their own potential as athletes and strategists. You wanted switch-hitters in your lineup even if by swinging from one side rather than the other the hitter sacrificed a little raw power for artifice and skill.

One of the contributors to the bisexual feminist anthologies Closer to Home and Bi Any Other Name describes herself as “a nine-time San Francisco Advertising Softball League all-star” who “rather likes the designation ‘switch-hitter.’ “2 The newsletter of the Boston Bisexual Women’s Network included a list of “Famous Switch-Hitters” (culled, interestingly, from a published book of Lesbian Lists2) that included Lady Emma Hamilton (“the mistress of both Queen Maria Caroline of Naples and Admiral Nelson”), Natasha Rambova (“wife of silent-screen heartthrob Rudolph Valentino, and sometime lover of [director] Alia Nazimova”), and Edith Lees Ellis, the wife of Havelock Ellis. (Who says feminists don’t have a sense of humor?) Switch Hitter is also the name of a Cambridge-based ‘zine for bi men and women. It’s clear from these wry appropriations, though, that “switch-hitter” in a sexual context has not been an automatic term of praise or pleasure.

What about AC/DC, a term used in the past, somewhat disparagingly, to suggest either a failure of sex and gender type or a wishy-washiness about sexual orientation (“he seemed a little AC/DC to me”). Again, it’s worth wondering how versatility and adaptability became such bad things. An appliance that works on both alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC) sounds handy, to say the least. Here’s what Brewer’s Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Phrase and Fable says about it: “[T]he expression originated in America by analogy with electrical devices adaptable for either alternating or direct current. It became popular in the UK during the 1960s and early 1970s.” Brewer’s thinks this term may be related to “the sexual imagery of electricity” in the “tradition of ‘male’ and ‘female’ connectors in wiring.”2 Plug it in anywhere, and it works.

So on the one hand we have American ingenuity and know-how, and indeed American sporting competitiveness. (Basketball, hockey, and tennis players also work to cultivate their even-handedness.) On the other we have resistance and reticence, sometimes even recoil and repugnance, at the idea that sexual versatility could include the widest range of consensual partners and pleasures. Sex isn’t supposed to be an invention, or a sport, or a labor-saving device.

Is it a sensory indulgence, like “having your cake and eating it, too”— yet another phrase that, with its variants, is often applied to the perceived situation of bisexuals? One bisexual woman in a committed monogamous relationship with another woman reports that her partner “felt that choosing a bisexual identity meant that I was declaring my sexual ambiguity— my need to have my cake and eat it, too.”2 What does this maxim mean? Is it the same as “having it both ways”? I don’t think so. To have it both ways is to have this and that. A married man who also has sex with men or boys could be said to “have it both ways,” whether or not that phrase was understood in its most limited anatomical sense. But is he “having his cake and eating it, too”? Who, or what, is the cake here? Here there’s a kind of cultural static interference, the original phrase having crossed wires somewhere along the way with “putting the icing on the cake,” which means wrapping up a victory beyond doubt, perfecting it, adding the finishing touches.

Is bisexuality the “icing on the cake” of homosexuality? Of heterosexual-ity? Or is bisexual living and loving the icing on the cake of bisexual feelings, bisexual desire?

The “having your cake” phrase is often understood to have a kind of economic subtext: “you cannot spend your money and yet keep it,” one reference book translates rather flatly, offering the additional, and seemingly contradictory analogy, “Ye cannot serve God and Mammon” (Matthew 6:24; Luke 16:13). The combination of the two seems to align God with spending and Mammon with keeping riches, in defiance of the usual assignment of spheres of influence to those competing authorities.

I have always thought “having your cake and eating it, too” meant not only a failure to save and ration pleasure but also a related gluttony or absence of reserve. If the stereotypical bisexual man with a wife and some male lovers on the side is treating his wife like surety or security and his lovers as pleasure, then maybe he is having his cake etcetera. That appears to be the point of the phrase when hurled, a little awkwardly (like a custard pie in the face?) as an epithet.

But most bisexuals, needless to say, do not think of themselves as “having it all” in the sense of an easy life. Many describe their isolation or ostracization from the gay or queer community, and their sense of apartness from the world of “heterosexual privilege” in which many gays and lesbians have thought them to be seeking refuge. If “having it all” and “having things both ways” imply repletion and total satisfaction even in the face of contradiction, “having your cake and eating it, too,” with its tacit monitory prefix (“you can’t have…”) suggests that retribution, whether from individuals or from society as a whole, is somehow on its way. (So there.)

I suspect that some of the animosity toward bisexuals, what the bi movement has come to call “biphobia,” is based upon a puritanical idea that no one should “have it all.” “Choice,” itself a contested word in some queer circles, is taken to imply choosing against, as well as choosing with —”not choosing” something as a way of choosing something else. And politically speaking, choosing a person rather than a label or category is often seen as denial rather than acceptance. Especially for those who feel they have “no choice” about their sexuality.

What’s in a Name?

It is my opinion that while the word bisexual may have its uses as an adjective,… it is not only useless but mendacious when used as a noun.

—John Malone, Straight Women/Gay Men2

My feeling is that labels are for canned food…. I am what I am—and I know what I am.

—R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, discussing “the whole queer-straight-bi thing” in Rolling Stone2

One thing that just about everyone agrees on is that “bisexual” is a problematic word. To the disapproving or the disinclined it connotes promiscuity, immaturity, or wishy-washiness. To some lesbians and gay men it says “passing,” “false consciousness,” and a desire for “heterosexual privilege.” To psychologists it may suggest adjustment problems; to psychoanalysts an unresolved Oedipus complex; to anthropologists, the narrowness of a Western (Judeo-Christian) world view. Rock stars regard it as a dimension of the performing self. Depending on the cultural context it can make (Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Sandra Bernhard) or break (preacher Jim Bakker; congressman Robert Bauman; even briefly, tennis star Billie Jean King) a career.

Talk-show hosts are convinced that “bisexuality” is a cover for unbridled lust, or what bisexual activists prefer to call “nonmonogamy.” Never mind that monosexuals, straight and gay, have practiced enthusiastic nonmonogamy for centuries.

“Back-formation” is a term from linguistics that describes the way words and concepts can be constituted retroactively, providing what is in effect a false pedigree in the form of a putative etymology. Strictly speaking, a back-formation is a new word created by removing a prefix or a suffix (or what is thought to be a prefix or a suffix) from an already existing word; thus our singular “pea” comes from subtracting the “s” from the earlier English plural, pease, and the modern slang “ept,” rather than the more literally correct “apt,” is created by removing the prefix from “inept.” This looks harmless enough, but it soon enters the realm of the political by way of an authenticating gesture toward origins. The logic of apparent priority—the illusion of priority produced by back-formation—creates a hierarchy of the “natural,” the “normal,” or the “original.”

What does back-formation have to do with bisexuality? In the broadest and most general sense, it explains why many people regard the “bisexual” as a variant—and often a perverse or self-indulgent variant—of the more “normal” practice of heterosexuality, rather than viewing heterosex-uality (or, indeed, homosexuality) as a specific personal or cultural option within a broader field that could be called simply “sexuality.” Historically speaking, the word “heterosexual” is a back-formation from “homosexual.” Before people began to speak of “homosexuals” as a kind of person, a social species, there was no need for a term like “heterosexual” (literally, sexually oriented toward the [or an] other sex). Both words date in English from around the turn of the century. Neither appears in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, the standard reference work, begun in 1879 and completed in 1928. Each makes its first appearance in the Supplement.

In English, then, the word “homosexual” dates from around 1897, when the sexologist Havelock Ellis introduced it in his Studies in the Psychology of Sex as a coinage of his fellow Victorian sex-writer and Eastern traveler Richard Burton. “ ‘Homosexual’ is a barbarously hybrid word,” wrote Ellis, “and I take no responsibility for it.” Ellis preferred other, less “hybrid” terms, like “sexual inversion,” based upon a notion of congenital and inborn sexual disposition toward persons of one’s own sex. He regarded sex as a positive force in human life, whether it took the form of masturbation, oral sex, intercourse, or a variety of other sexual pleasures. Himself married to a bisexual woman, Ellis proposed “trial marriages” before partners made lasting commitments to each other, recognized the pleasures of variety in sexual partners, and offered a critique of the institution of marriage, which he called “rather… a tragic condition than a happy condition.”

His deprecation of the new word “homosexual” does not reflect a negative attitude toward homosexual behavior, but rather a classically trained scholar’s resistance to blending Greek (homo, same) and Latin (sexus) roots. But the resistance, however philological, is worthy of note. A question of authenticity and origins is being raised here; the naturalizing of the term “homosexual” is made more difficult by its problematical parentage —a parentage which, significantly, is “hetero” rather than “homo.” (This is made even more problematic by the apparent homology between the Greek adjective homos, meaning “same” and the Latin noun homo, meaning “man, human being.” The false etymology “man-lover” or “desirer of men” crosses the “true” etymology of “lover or desirer of the same [sex].” The term “het” for a heterosexual person, now in common use among gays, lesbians, queers, and bi’s, is yet another example of a back-formation, this one troped on “homo,” a disparaging term for a gay or homosexual person. (Quentin Crisp, for example, referred to himself as having become a national institution, one of the “stately homos of England.”) For a person who regards himself or herself as part of the mainstream, “het” is a reminder of the way in which the familiar can be defamiliarized, the unmarked term become marked, the “self turned into someone else’s “other.”

“Heterosexuality” is, in a way, begotten as a term by its elder sibling, “homosexuality.” In fact, the first definition in the Oxford English Dictionary betrays some of this anxiety of origin. “Pertaining to or characterized by the normal relation of the sexes,” it says, begging the question of the “normal.” “Opposite to homosexual’.” And then, immediately, “Sometimes misapplied, as in quote 1901,” the first recorded use of the term, in Dor-land’s Medical Dictionary. InDorland, “heterosexuality” is defined as an “abnormal or perverted sexual appetite towards the opposite sex.” This is, indeed, we might say, a “misapplication” if the standard definition posits, without specifying, a “normal” relation “of the sexes.” But what significance might there be in the fact that not only does “homosexuality” precede “heterosexuality,” but the “abnormal” practice of something called “heterosexuality” precedes its usage in the language as a term for a “normal relation o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Praise for Bisexuality

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction Vice Versa

- Part I Bi Ways Culture, Politics, History

- Part II Bi-ology Science, Psychoanalysis, Psychomythology

- Part III Bi Laws Institutions of “Normal Sex”

- Part IV Bi Sex The Erotics of the Third

- Notes

- Index

- Permissions

- Photo Credits