![]() Part One

Part One![]()

1

Foundations and Philosophy of Supervised Practice

In the earliest days of student affairs work, the Student Personnel Point of View (American Council on Education, 1937) emphasized educating “the whole person” so that individuals can reach their full potential as the essential purpose of the student affairs profession (Roberts, 2012). The higher education landscape has changed dramatically in the 75 years that have followed. Students are increasingly diverse in terms of age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, gender identities, career goals, personal philosophies, political preferences, and reliance on technologies unimagined among students of previous generations. New roles have emerged for administrators in higher education, such as work with graduate students, engagement with alumni in mutually beneficial ways, and providing risk management guidance. Higher education institutions have also changed. We see new approaches not envisioned just a few years ago happening with increasing speed, such as massive online learning initiatives, new academic majors related to technology, appealing building amenities, branding strategies to attract donors, and substantial efforts to contribute to the economic development of communities and states.

The pace and complexity of change among students and institutions will likely increase (Levine & Dean, 2012; Selingo, 2013). Therefore, student affairs professionals will be required to manage contexts that are continually more ambiguous and where students and other constituents desire a much greater degree of responsiveness. How then does a new student affairs professional balance commitment to the core purpose of enabling students to reach their full potential (Lampkin, 2007) with the challenges of working within increasingly complex higher education institutions?

It becomes ever more important that practitioners learn quickly and continuously; they must know their values, skills, and how they learn best. Effective preparation for the student affairs profession includes both classroom instruction and supervised practical experience, such as internships or graduate assistantships (Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education [CAS], 2012). Formal classroom education alone— with specified learning outcomes, regular and structured feedback, and educational experiences carefully designed by the instructor— is necessary, but not sufficient, to prepare students for the daily struggle of professional practice. Although supervised practice experiences have historically been required components of preparation programs’ curricula (McEwen & Talbot, 1977), carefully designed and executed experiences are even more critical learning opportunities for enabling new professionals to thrive within the rapidly changing higher education milieu.

Through a practicum, assistantship, or internship experience, students learn nimble thinking, recognize the nuances in a workplace, read the intentions of coworkers and supervisors, and take individual initiative to create solutions that fit the organizational culture. With the guidance of a faculty or site supervisor, students are able to address real-world issues and develop tacit knowledge— the kind of practical wisdom that allows for seemingly intuitive problem solving (Reber, 1993). In addition, supervised experience develops a trajectory of increasingly complex thinking that will likely generalize to new situations, such as those encountered in a first professional position (Sheckley & Keeton, 2001).

The structure of the supervised experience as well as the skill of both the faculty and site supervisors are key variables in determining whether a particular internship will meet the lofty goals of developing practical wisdom and complex problem solving. However, an equally important determinant of the value of a supervised practical experience is the individual student’s ability to know and adapt his or her learning approaches, even if it means using a style that is not comfortable or natural.

Reflection Activity

Take a look at the following two stories— one of Marcia and one of Elliott. Each story describes very different desires for the supervised practice experience. As you read the stories, think of which elements of each person’s approach are most like your preferences and which are least like your preferences. Then, reflect on the questions that follow each story.

Marcia—Marcia has a reputation within her cohort as the one who can best go with the flow. She is very creative, often identifying novel, unexpected solutions to the problems that are presented. Sometimes her solutions are unrealistic or the implementation is less attentive to details. However, her intuitive understanding of students’ needs often makes her ideas very powerful contributions, especially to the case study and simulation exercises required in her student development and leadership courses.

Marcia wants to find an internship site that will allow her to be creative and where she can work independently. She wants a supervisor who will let her explore possibilities rather than providing too much structure. She wants an open-minded supervisor who is willing to help her make sense of her observations. She does not want a site that requires substantial assessment or writing tasks since she would prefer working directly with students because their needs are often unpredictable.

Marcia wants her schedule to be flexible so that she can take advantage of the unexpected things that she might learn through observation and problem solving. She is open to a wide variety of experiences, even those that are planned at the last minute.

Elliott—His fellow students and faculty members know El as an excellent planner. He has an extraordinary capacity to manage details and to make sure that every possible contingency is covered. Although he is reliable and consistent in his classwork performance, there are times when he has trouble finding creative solutions to problems in the moment.

When thinking about a supervised practice experience, Elliott indicates he wants a supervisor who gives clear direction and detailed guidance— especially before Elliott makes a decision. Elliott’s goal is to make sure that he does his tasks correctly, so he hopes that early in the experience the supervisor will share details about the history and context of the site so that he can design workable plans.

Elliott would prefer writing, assessment, and project-planning tasks to be the central focus of the supervised practice experience. With these types of tasks, he could better control achievement of his specific goals and outcomes for the experience. It is important for Elliott to have a predictable schedule, since he knows he is more effective when he can anticipate what tasks can be expected and planned for.

Assumption: In nearly all student affairs offices, elements of both Marcia’s and Elliott’s approaches would be useful, depending on the specific situation. The following questions will help you articulate your natural preferences and others that may not be preferred but need to be developed.

Questions

- Which of the two stories is most like you (even if it is not exactly a match) in terms of these elements:

- Preferred relationship with supervisor?

- Preferred degree of personal control of the activities?

- Preferred degree of structure provided by the site?

- Preferred degree of prior planning?

- Other elements?

- Describe in detail your preferences in terms of these elements:

- Preferred relationship with supervisor?

- Preferred degree of personal control of the activities?

- Preferred degree of structure provided by the site?

- Preferred degree of prior planning?

- Other elements?

- Describe what would be least preferable in terms of these elements:

- Preferred relationship with supervisor?

- Preferred degree of personal control of the activities?

- Preferred degree of structure provided by the site?

- Preferred degree of prior planning?

- Other elements?

- How might you develop your capacity as a learner in your upcoming supervised practice experience? Think about how you can stretch beyond your natural preferences.

Purpose of Chapter 1

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the supervised practice experience. We present a description of an intentional student affairs practitioner, the components of which constitute the learning domains essential for professional practice. Depending on the precise nature of the supervised practice, effective experiences should address all of these learning domains and competencies, to varying degrees. These learning domains can be seen as targets— potential goals to contemplate as one begins a new supervised practice experience. The chapter also incorporates adult and experiential learning theories that can help students and supervisors conceptualize and plan their approaches for supervised learning experiences. Finally, we discuss specific ways that students can enter a new supervised practice site so that learning from the particular office will be most powerful.

What Is Supervised Practice?

Since the middle of the last century, scholars have contended that a structured application of practice component is essential for graduate preparation in student affairs (Delworth & Hanson, 1980; Greenleaf, 1977; Knock, 1977; McGlothlin, 1964). Currently, the most recent CAS requirements for master’s-level student affairs preparation programs mandate that a structured practical experience be included as part of a graduate preparation program. Specifically, these standards mandate that students complete “[a] minimum of 300 hours of supervised practice, consisting of at least two distinct experiences” (CAS, 2012, p. 356).

Although student affairs professionals at all levels can benefit from material in this book, students enrolled in a preparation program at the master’s or doctoral level and who desire a career in higher education administration are the primary audience. For the purposes of this book, several conditions are necessary for an experience to be categorized as supervised practice. First, the supervised practice experience is designed to give students an opportunity to engage in meaningful professional-level work. Some examples of meaningful professional-level work include advising individual students, planning alumni programs, managing student organization budgets, facilitating workshops, or supervising paraprofessionals. During supervised practice, the student’s experience occurs as part of the work of an office or functional unit in a higher education institution. Part of the power of supervised practice is the connection between the student’s intentions and the constraints or opportunities imposed by a particular organizational environment— with its distinctive culture, politics, power structure, and leadership. Finally, a more seasoned administrator in a college or university carefully supervises the experience.

Many types of experiences can be classified as supervised practice in this context, including these:

- Graduate assistantships. In these roles, students are paid paraprofessionals charged to accomplish regular and sustained job duties. Most often, students are evaluated on the degree to which they contribute to the initiatives of the office that employs them. Students’ achievement of their own learning objectives is most often not the primary emphasis of the experience.

- Volunteer supervised experiences. In many preparation programs, master’s or doctoral students are recruited to provide short-term programs or services that are unpaid or for which they are given a small honorarium. These might include facilitating workshops or trainings, teaching a discussion section of a course, or advising a student organization. In these experiences, students do not receive academic credit.

- Internships that are not for credit. Master’s or doctoral students may take on a fixed-duration supervised internship where there is no credit offered, but students receive remuneration for expenses or a stipend, or both. For instance, several professional organizations (e.g., National Orientation Directors Association [NODA]; Association of College and University Housing Officers-International [ACUHO-I]) offer these types of opportunities during the summer. Within some preparation programs students can earn academic credit for classes associated with these professional association–sponsored internships or for other summer internships.

- Internships that receive credit. Master’s or doctoral students take on supervised practice experiences that last for a fixed duration and that are often unpaid. On many campuses these experiences are termed practicums. Their primary purpose is to further students’ learning goals, although internship students also provide assistance to the sponsoring office in service-delivery, program-planning, or other tasks. Supervision in this type of internship typically involves two individuals: the site supervisor, who is a staff member in the office sponsoring the internship, and the academic supervisor, who is a faculty member. (Chapter 3 contains more details how to work with supervisors in a variety of institutional roles.)

Although the material contained in this book can easily be adapted for all of the supervised practice experiences outlined previously, there is particular emphasis on experiences that occur in conjunction with an academic course.

The Intentional Student Affairs Practitioner

Student affairs practitioners are expected to fulfill a variety of roles within their institutions; paramount among them are educator, leader, and manager (Creamer, Winston, & Miller, 2001). These roles carry with them certain values and a need for theoretical knowledge, ethical strictures, applied knowledge, and skills that enable professionals to facilitate both the formal and informal processes of learning in colleges and universities. They are humanists and pragmatists (Winston & Saunders, 1991) who enable the achievement of potential in the people with whom they work, yet they are managers of resources and of people who must achieve institutional as well as individual aims. All of these roles must be conducted in an ethical environment where all educational activities are firmly and directly targeted to achieve the most basic purposes of education: individual and community development.

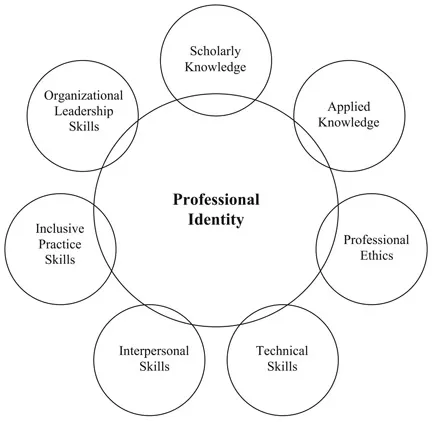

Figure 1.1 Model of professional identity.

Figure 1.1 depicts the seven learning domains that should be addressed and revisited by student affairs professionals as they journey through their careers. Although most professional preparation programs include these domains in their curriculum, the achievement of these comprehensive educational objectives is certainly not fully realized at the close of a master’s or doctoral program. The domains are related to the more specific professional competencies developed by the American College Personnel Association/National Association of Student Affairs Professionals (ACPA/NASPA) (2010) and also to a number of research articles that identify the salient professional competencies required of new professionals (Cuyjet, Longwell-Grice, & Molina, 2009; Herdlein, 2004; Lovell & Kosten, 2000; Renn & Hodges, 2007; Waple, 2006) and more advanced doctoral graduates (Saunders & Cooper, 1999). Attending to these learning domains is integral to achieving the educational goals of supervised practice.

Addressing the learning domains, however, is not enough to realize the maximum benefit from a supervised practice experience. These learning domains are inextricably entwined with one’s professional identity that encompasses beliefs about professional behavior, management philosophy, and effective learning strategies among other elements. Fundamentally, professional identity is the way professionals define themselves, as well as their integrity in translating that definition to practice. Professional identity is the lens that interprets the meaning of the seven learning domains and fosters their application to authentic professional practice.

In no particular hierarchy, the learning domains are scholarly knowledge, applied knowledge, professional ethics, tec...