Chapter 1: Graceful manliness, unfeminine maidens and erotic gods

Male aerial gymnasts were doing flying acts by 1860 and several female performers are identifiable by 1868, imitating the flying action of males. As early as 1862, 10-year-old Natalie Foucart on fixed trapeze, with muscles like ‘a big boy's’, aspired to copy and outdo Léotard, the first flyer (Munby 1972: 122). The aerialists performing on the new trapeze apparatus were quick to explore the greater possibility of appearing to fly by executing strenuous physical leaps, dives and turns between combinations of trapeze bars and hanging ropes from suspended platforms. They embodied long-standing cultural aspirations for flight.

Aerialists in the nineteenth century were attributed physical qualities that mixed up their gender identity. The aerial action of males was praised for manly daring and for graceful lightness and poise, qualities of movement that were more conventionally the preserve of femininity. Similarly, female aerialists were described as beautiful, and as adventurous and courageous, traits considered manly. Male and female aerialists alike were admired for their muscular development.

In becoming airborne and overcoming the existing limits to physical action, aerialists exemplified later nineteenth-century scientific advancement and pronouncements about evolutionary theory. Paradoxically, wingless flying invited poetic responses of wonder and astonishment that elevated it beyond humanness, as if performers were superhuman and god-like. Flying acts evoked ideas of freedom from the constraints of everyday movement, reinforced by the defiance of gravity, of natural laws.

Muscular flying action

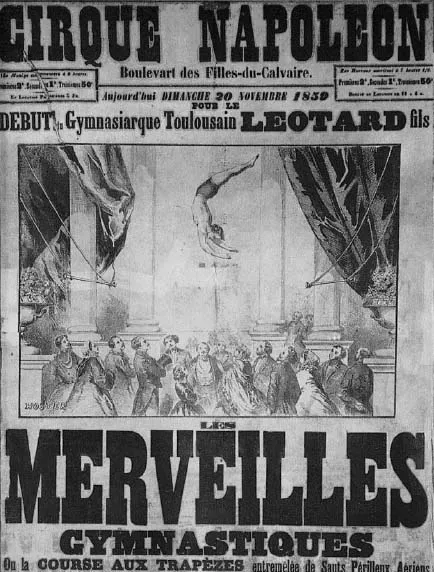

Jules Léotard is widely recognized as the inventor of flying trapeze action. His action involved leaving one swinging trapeze and leaping forward to grab hold of a second, and then a third (see Figure 1.1). While a number of male performers quickly copied Léotard's act – some easily surpassing its athletic achievement – no one equalled his legendary status. Not only was Léotard an inventive athlete but, according to the accounts of audience members, he also moved with exceptional grace. It was the lightness and ease of Léotard's muscular action as much as his physical skill, daring and creative inventiveness that contributed to his reputation. Performance on trapeze has parallels with dance because it expresses an artistic sensibility through the quality of a body's movement.

Figure 1.1 Léotard poster, courtesy of Dr Alain Frere's private collection.

The year 1859 is of major significance in aerial history for two events: Léotard debuted in Paris, and French rope-walker Blondin (Jean François Gravelet) crossed Niagara Falls, both greatly surpassing the existing limits of physical action. Steve Gossard's (1994) research locates trapeze-like apparatus in earlier performance as well as leaps to ropes and between ladders, which confirms an intriguing and unstable history of equipment invention and technique innovation.1 The basic trapeze had a horizontal wooden (later metal) bar wrapped with fabric, suspended between two hanging, vertical ropes, also covered near the bar. The Siegrist Brothers are credited with introducing the trapeze to North America, although it was the Hanlon-Lees Brothers and their Zampillaerostation (trapezes in a line) that became star attractions in New York in 1861 (McKinven 1998: 15). Trapeze had reached Australia by 1863 with Charles Perry (St Leon 1983: 123). Aerial performance history is one of exceptional athletic feats, and although it is a contested account of who came first, Léotard established the performance precedent for the action of unencumbered leaps and somersaults between trapezes termed ‘flying’.

While the term ‘Bird-man’ was used for traditional rope-dancers, and some were even called voleur (flyer) (Russell and Depping 1871: 172), the action of flying unaided through the air away from the apparatus made the trapezist more like a bird in flight than simply elevated up with the birds on a rope. Social ideas were changing and after 1798 the flight of birds, long associated with divinity and the soul, was explained by the action of bird ‘muscles’ (Hart 1985: 28–9, 56 (Paul-Joseph Barthez)). Hot-air balloons facilitated becoming airborne through mechanical means, but human bodies that flew unaided were irresistible attractions drawing large audiences. As theatre attests, with mechanical apparatus for staging flying traceable back to classical Greece (McKinven 2000: 1), mastery of the air was both an imagined ideal and a practical pursuit. Apparatus for suspending bodies, adapted from Europe's fairgrounds, was used within nineteenth-century ballets, and rope-dancing positions corresponded with ballet positions (Winter 1964: 103, 108). Léotard was developing his aerial skills in France at a time when French ballet, rope-dancing spectacles and ‘wordless theatre’ were widely emulated (ibid.: 18), and French aviation experiments became central to progress in mechanical flight invention during the 1850s and 1860s (Gibbs-Smith 1985: 31–41). In theatres and circuses after 1860, aerialists on trapeze, often with assumed French names, evoked long-held artistic, cultural and scientific ambitions.

Léotard may have performed in the provinces before his famous debut, on 12 November 1859, with Franconi's at Cirque Napoléon, Paris, later to become the important fixed venue Cirque d'Hiver.2 His Austrian father, Jean, ran a gymnastic school in Toulouse, and Léotard reportedly practised over the swimming baths into which he could fall if he missed the bar. The conventional account is that he invented the trapeze himself after noticing nearby hanging ropes. But a triangular type of apparatus had been available to men and women for calisthenics from the 1820s; equipment in gymnasiums resembled an aerial rig, and the label ‘gymnast’ was used interchangeably with ‘trapezian’. The presence of Léotard's father on a narrow platform swinging his trapezes towards him, and his mother as his offstage dresser with chalk to dry his hands, confirms that this was certainly a family act, and the likelihood is that he was physically trained from childhood (Hollingshead 1895: 212; Léotard 1860: 24). In 1860 Léotard leapt across 27 feet, at a height of 15 feet.3 He was ‘modest’ in his lavender leggings, black velvet shorts and black leather boots, working with ‘unerring certainty’ while his graceful ‘movements were more like those of a bird than of a man’ (Hollingshead 1895: 213–14). Like acrobats, Léotard wore knitted leg hose – stockings were a male fashion from the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries. But his unique design of a neck-to-fitted-crotch singlet facilitated easier movement and it also displayed his body to advantage (Léotard 1860: 187–8). Léotard set the precedent for aerial flying, and gave his name to the costume subsequently worn with flesh-coloured tights called ‘fleshings’, so that legs seemed bare.

Swinging across an auditorium holding (or standing on) a trapeze bar, Léotard let go and executed a single somersault before grabbing a second swinging trapeze bar. Accounts vary and in some venues there was an iron frame and later up to five trapezes (Rendle 1919: 205). Léotard may have let go from the downward swing to maintain his momentum.

Nineteenth-century observers were attentive to muscular appearance. Englishman Arthur Munby writes, ‘The man himself, Léotard, was beautiful to look upon; being admirably made and proportioned; muscular arms shoulders and thighs; and calf ankle and foot as elegantly turned as a lady's’ (1972: 97). Englishman Thomas Frost confirms the grace of Léotard's action (1881: 153). A muscular small body suited aerial performance, but such observations about the relative proportions of male and female bodies also indicate the scientific propensity to objectify and describe nature and allocate set measurements, as well as the influence of idealized bodies from Graeco-Roman art. A premise of scientific enquiry, however, scarcely masked the underlying erotic allure of some bodies.

Written in the style of diaries of the day, Léotard's memoirs recount his unassailable popularity with women and hint at sexual liaisons, but claim that the male body is more beautiful than the female (1860: 188). He verifies his manliness with claims about his large audience of women from all classes, some of whom fought to get better seats and sent him adoring letters. A newspaper satire suggests some veracity to these claims.4 Léotard implies that women attend to admire his body as much as his act.

Is it surprising, then, that other aerialists immediately imitated Léotard's physical action even from hearsay, and appropriated his trademark name? Within months his act was reproduced by Richard Beri and James Leach in London, who performed before him at the Alhambra music hall. Victor Julien, ‘the only gentlemanly artiste’,5 copied Léotard's single somersault between bars, and there were appearances by Verrecke and Bonnaire (Frost 1881: 153). The risks of the action increased as the tricks became more arduous under pressure to outdo other performers. After the addition of extra trapeze bars, and after one somersault between two bars had been mastered, the somersault was doubled, and the distances between the trapezes increased. From 1868 performers doing double somersaults between bars included Niblo (Thomas Clarke), who probably set the precedent (Speaight 1980: 74). If Niblo's graceful feats as Flying Man surpassed what was imagined for ‘human effort’,6 close behind were other performers. Onra was soon advertising a 150-foot leap,7 and double somersaults (ibid.: 74), and there was also Avolo, whose ‘motive power’ to spring from one bar to another was mystifying.8 Dressed as a female, Lulu did three somersaults down to a mattress (see Chapter 3), thereafter bettered by Cleo doing four somersaults to his net, and reassuring the audience that ‘all idea of danger is banished’.9 Despite this proliferation of acts, by the 1870s aerial gymnasts in England were probably less than a third of the 120 to 150 acrobats and gymnasts listed annually in The Era Almanac.

Aerial performance suited a growing public penchant for spectacle. The competitive pressures from other aerialists and the need to improve on tricks in order to maintain audience interest were accompanied by competition from exciting new visual technologies. On his return to the Alhambra in 1861 with ‘feats hitherto unattempted’, Léotard performed in a programme that included a painted scene, a diorama, of political events in England's colony, India.10 Circus was becoming known for spectacles of nationalities, albeit with creative license, and Frost notes that Andrew Ducrow staged his first ‘gorgeous Eastern Spectacle’ in 1830 at Astleys (1881: 61). Helen Stoddart recognizes the complicity of circus in representing public events (2000: 86). If the orientalism and imperialism of circus spectacles is unmistakable (ibid.: 102–3; Davis 2002: 199–206), a glorification of violence also became part of their depiction of military engagements. Even though it did not in itself present an imperialist narrative, aerial performance could not be considered innocuous within the sequential programming of a range of acts in variety shows. There was a metacultural significance in the juxtaposition of flying acts demonstrating bodily mastery of air space and spectacles presenting expansionist stories of conquered geographical space. Prior to this, the German gymnastic movement promoted patriotic virtue and xenophobia through the development of superior physicality but, as it spread throughout Europe, by the 1880s it would contradictorily also become associated with cultural tolerance (Ueberhorst 1979). A demonstration of the capacity to overcome the known limits of mobility in space existed in an ideological continuum. Aerial performance confirmed a belief that European culture was headed towards an unstoppable domination of the natural world and non-European societies. Abstract aerial performance did not replay political events, but it fitted alongside spectacles that validated nineteenth-century ideas of empire and spatial domination.

When the now-famous Léotard performed his twelve-minute act across the Atlantic in New York on 29 and 30 October 1868, competitive standards within aerial performance meant that he was no longer the leading sensation. His imitators had pre-empted him. Léotard performed after ten in the evening, following a comic pantomime and with six to eight attendants securing the guy ropes for his apparatus. The reviewer writes,

Grasping two handles attached to long ropes hanging from the dome, he started on his aerial journey swaying through the air backwards and forwards alighting each time on the iron frame as lightly as a bird. This he repeated several times. The next feat was swinging from this frame and catching a second trapeze midway between the frame and the back of the stage … and with his head downwards turns a half somersault and catches the second bar – while it is swinging – with his hands, and alights on the frame at the back of the stage.11

The reviewer is unimpressed with Léotard's somersault, wanting to be ‘electrified’ rather than ‘simply pleased’, and explains that the Russian Pfau performing with the Hanlon-Lees Brothers is just as daring.

What motivated these performers to undertake aerial work and risk injury? Most started performing as children or adolescents, but a few were adults seeking a challenge or seizing an opportunity for work that was often scarce. Frost recounts how two males imitated a trapeze duo in which one dropped head-first down the body of the other, who caught him with his feet, and although they initially earned £5, they became disappointed with the unpredictability of their weekly earning capacity (1881: 255–60). Crowd-pleasing celebrity performers who were well managed, however, earned big incomes. Léotard earned £100 a week in London in 1860, and subsequently earned £30 a night (Hollingshead 1895: 213). An innovative aerial act could earn in a week the equivalent of half a year's pay for an ordinary worker. By the mid-1870s in North American circus, acrobats and gymnasts were paid between $25 and $100 weekly – one refused $125 – and females could receive ‘fancy’ amounts.12 One reason that aerialists were condemned in some newspapers was that they were perceived to take risks for money.13 Although public efforts to ban aerial acts intensified – fuelled by literary depictions of adult cruelty to child acrobats (Steedman 1995: 100–2) – these were not successful even in England.

The appeal of aerial performance was not simply its sensationalism, but also its artistry of abstract movement delivered seemingly effortlessly. This evolved from unsupported leaps through the air to turns and twists metaphoric of playfulness – the performance of exuberance. Perceptions of aerialists as bird-like were compounded by their abstract physicality. The execution of somersaults curled up, ball-like, as well as complex pirouettes and twists, in which the performer turns his or her full-length body, would become the mark of great flyers. By the late nineteenth century flyers sought to master a mid-air triple backward somersault to the hands of a catcher – following the earlier often injurious efforts of ground-based acrobats called ‘leapers’ or ‘vaulters’ (Gossard 1990).

Importantly, aerial performance became a muscular contest that repeatedly pushed beyond its existing limits. Performers promoted themselves as muscular athletes: Adair's ‘muscular strength is something out of the common order of things’.14 New inventions and modifications of aerial apparatus extended the capacity to contort in precarious mid-air balances. In 1867 C. S. Burrows was balancing on ladders and chairs on a trapeze.15 Two performers could balance and do handstands at either end of a ladder horizontally across a suspended platform. Novelty acts developed; for example, the Alfredo family suspended a trapeze under a bicycle on a wire in the 1870s (Slout 1998a: 4). By 1870 American Keyes Washington had a small metal saucer screwed into the centre of the trapeze bar to allow a head balance with the upside-down body inclined (Speaight 1980: 72–3). (In the mid-twentieth century, female aerialists Pinito Del Oro from Spain and Russian Elly Ardelty, with a one-leg stand, were the leading artists of the spectacular trapeze Washington balancing act.)

Aerial performance was popular if not quite respectable, and perhaps it became less acceptable once women began performing in the late 1860s. Charles Russell, translating and enlarging on Guillaume Depping's Wonders of Bodily Strength and Skill …, dismisses Léotard's trapeze act as short-lived, low-class entertainment that appeared to be ‘dying out’ (1871: 185). Rope performance, however, was acceptable because of its illustrious heritage and royal patronage on ceremonial occasions. Adherence to the ‘cultural developmentalism’ of humans advancing from biblical peoples meant that nineteenth-century industrial society was considered a triumph of mental abilities denied to so-called savage peoples (Stocking 1987: 183–5). Earlier cultures, including Greek and Roman, depended on physical strength, and were therefore more primitive. This made nineteenth-century physical displays anomalous within linear creationist ideas of social development. Thus during the 1860s Russell and Depping and others would condemn trapeze performance as primitive and degenerate because it involved physical display. It might be new action but it denoted the past, when ‘adoration was paid to physical beauty’ and strength and sporting contests happened between nations (Russell 1871: 12).

Prejudices against gymnasts, however, underwent a transformation during the 1870s when socio-cultural evolutionism came more fully under the sway of Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), with its controversial ideas of natural selection and human descent from apes (Stocking 1987: 147), in combination with H...