eBook - ePub

Working with Specialized Language

A Practical Guide to Using Corpora

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Working with Specialized Language: a practical guide to using corpora introduces the principles of using corpora when studying specialized language. The resources and techniques used to investigate general language cannot be easily adopted for specialized investigations. This book is designed for users of language for special purposes (LSP). Providing guidelines and practical advice, it enables LSP users to design, build and exploit corpus resources that meet their specialized language needs. Highly practical and accessible, the book includes exercises, a glossary and an appendix describing relevant resources and corpus-analysis software. Working with Specialized Language is ideal for translators, technical writers and subject specialists who are interested in exploring the potential of a corpus-based approach to teaching and learning LSP.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Setting the scene

1 Introducing corpora and corpus analysis tools

Simply speaking, corpus linguistics is an approach or a methodology for studying language use. It is an empirical approach that involves studying examples of what people have actually said, rather than hypothesizing about what they might or should say. As we will see, corpus linguistics also makes extensive use of computer technology, which means that data can be manipulated in ways that are simply not possible when dealing with printed matter. In this chapter, you will learn what a corpus is and you will read about some different types of corpora that can be used for various investigations. You will also get a brief introduction to some of the basic tools that can be used to analyse corpora. Finally, you will find out why corpora can be useful for investigating language, particularly LSP.

What is a corpus?

As you may have guessed, corpus linguistics requires the use of a corpus. Strictly speaking, a corpus is simply a body of text; however, in the context of corpus linguistics, the definition of a corpus has taken on a more specialized meaning. A corpus can be described as a large collection of authentic texts that have been gathered in electronic form according to a specific set of criteria. There are four important characteristics to note here: ‘authentic’, ‘electronic’, ‘large’ and ‘specific criteria’. These characteristics are what make corpora different from other types of text collections and we will examine each of them in turn.

If a text is authentic, that means that it is an example of real ‘live’ language and consists of a genuine communication between people going about their normal business. In other words, the text is naturally occurring and has not been created for the express purpose of being included in a corpus in order to demonstrate a particular point of grammar, etc.

A text in electronic form is one that can be processed by a computer. It could be an essay that you typed into a word processor, an article that you scanned from a magazine, or a text that you found on the World Wide Web. By compiling a corpus in electronic form, you not only save trees, you can also use special software packages known as corpus analysis tools to help you manipulate the data. These tools allow you to access and display the information contained within the corpus in a variety of useful ways, which will be described throughout this book. Essentially, when you consult a printed text, you have to read it from beginning to end, perhaps marking relevant sections with a highlighter or red pen so that you can go back and study them more closely at a later date. In contrast, when you consult a corpus, you do not have to read the whole text. You can use corpus analysis tools to help you find those specific sections of text that are of interest—such as single words or individual lines of text—and this can be done much more quickly than if you were working with printed text. It is very important to note, however, that these tools do not interpret the data—it is still your responsibility, as a linguist, to analyse the information found in the corpus.

Electronic texts can often be gathered and consulted more quickly than printed texts. To gather a printed corpus, you would probably have to make a trip to the library and then spend some time at the photocopier before heading home to sit down and read through your stack of paper from beginning to end. In contrast, with electronic resources such as the Web at your disposal, you can search for and download texts in a matter of seconds and, with the help of corpus analysis tools, you can consult them in an efficient manner, focusing in on the relevant parts of the text and ignoring those parts that are not of interest. Because technology makes it easier for us to compile and consult corpora, electronic corpora are typically much larger than printed corpora, but exactly how large depends on the purpose of your study. There are no hard and fast rules about how large a corpus needs to be, but we will come back to this issue when discussing corpus design in more detail in Chapter 3. Basically though, ‘large’ means a greater number of texts than you would be able to easily collect and read in printed form.

Finally, it is important to note that a corpus is not simply a random collection of texts, which means that you cannot just start downloading texts haphazardly from the Web and then call your collection a ‘corpus’. Rather, the texts in a corpus are selected according to explicit criteria in order to be used as a representative sample of a particular language or subset of that language. For example, you might be interested in creating a corpus that represents the language of a particular subject field, such as business, or you might be interested in narrowing your corpus down even further to look at a particular type of text written in the field of business, such as company annual reports. As we will see, the criteria that you use to design your corpus will depend on the purpose of your study, and may include things like whether the data consists of general or specialized language or written or spoken language, whether it was produced during a narrow time frame or spread over a long period of time, whether it was produced by men or women, children or adults, Canadians or Irish people, etc.

Who uses corpora?

Corpora can be used by anyone who wants to study authentic examples of language use. Therefore, it is not surprising that they have been applied in a wide range of disciplines and have been used to investigate a broad range of linguistic issues. One of the earliest, and still one of the most common, applications of corpora was in the discipline of lexicography, where corpora can be used to help dictionary makers to spot new words entering a language and to identify contexts for new meanings that have been assigned to existing words. Another popular application is in the field of language learning, where learners can see many examples of words in context and can thus learn more about what these words mean and how they can be used. Corpora have also been used in different types of socio-linguistic studies, such as studies that examine how men and women speak differently, or studies comparing different language varieties. Historical linguists use corpora to study how language has evolved over time and, within the discipline of linguistics proper, corpora have been used to develop corpus-based grammars. Meanwhile, in the field of computational linguistics, example-based machine translation systems and other natural language processing tools also use corpus-based resources. Throughout the remainder of this book, you will learn about other applications of corpora, specifically LSP corpora, in disciplines such as terminology, translation and technical writing.

Are there different types of corpora?

There are almost as many different types of corpora as there are types of investigations. Language is so diverse and dynamic that it would be hard to imagine a single corpus that could be used as a representative sample of all language. At the very least, you would need to have different corpora for different natural languages, such as English, French, Spanish, etc., but even here we run into problems because the variety of English spoken in England is not the same as that spoken in America, Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, etc. And within each of these language varieties, you will find that people speak to their friends differently from the way they speak to their friends’ parents, and that people in the 1800s spoke differently from the way they do nowadays, etc. Having said this, it is still possible to identify some broad categories of corpora that can be compiled on the basis of different criteria in order to meet different aims. The following list of different types of corpora is not exhaustive, but it does provide an idea of some of the different types of corpora that can be compiled. Suggestions for how you can go about designing and compiling your own corpora that will meet your specific needs will be presented in Chapters 3 and 4.

General reference corpus vs special purpose corpus: A general reference corpus is one that can be taken as representative of a given language as a whole and can therefore be used to make general observations about that particular language. This type of corpus typically contains written and spoken material, a broad cross-section of text types (e.g. a mixture of newspapers, fiction, reports, radio and television broadcasts, debates, etc.) and focuses on language for general purposes (i.e. the language used by ordinary people in everyday situations). In contrast, a special purpose corpus is one that focuses on a particular aspect of a language. It could be restricted to the LSP of a particular subject field, to a specific text type, to a particular language variety or to the language used by members of a certain demographic group (e.g. teenagers). Because of its specialized nature, such a corpus cannot be used to make observations about language in general. However, general reference corpora and special purpose corpora can be used in a comparative fashion to identify those features of a specialized language that differ from general language. This book will focus on special purpose corpora that have been designed to help LSP learners, hence we often refer to the corpora in this book as LSP corpora. If you would like to find out more about general reference corpora, look at resources such as Aston and Burnard (1998) and Kennedy (1998).

Written vs spoken corpus: A written corpus is a corpus that contains texts that have been written, while a spoken corpus is one that consists of transcripts of spoken material (e.g. conversations, broadcasts, lectures, etc.). Some corpora, such as the British National Corpus, contain a mixture of both written and spoken texts. The focus in this book will be on written corpora, but if you would like to know more about spoken corpora and the challenges involved in transcribing texts, please refer to Leech et al. (1995).

Monolingual vs multilingual corpus: A monolingual corpus is one that contains texts in a single language, while multilingual corpora contain texts in two or more languages. Multilingual corpora can be further subdivided into parallel and comparable corpora. Parallel corpora contain texts in language A alongside their translations into language B, C, etc. These are described in detail in Chapter 6. Comparable corpora, on the other hand, do not contain translated texts. The texts in a comparable corpus were originally written in language A, B, C, etc., but they all have the same communicative function. In other words, they are all on the same subject, all the same type of text (e.g. instruction manual, technical report, etc.), all from the same time frame, etc.

Synchronic vs diachronic corpus: A synchronic corpus presents a snapshot of language use during a limited time frame, whereas a diachronic corpus can be used to study how a language has evolved over a long period of time. The work discussed in this book will be largely synchronic in nature, but more information on diachronic corpora can be found in Kytö et al. (1994).

Open vs closed corpus: An open corpus, also known as a monitor corpus, is one that is constantly being expanded. This type of corpus is commonly used in lexicography because dictionary makers need to be able to find out about new words or changes in meaning. In contrast, a closed or finite corpus is one that does not get augmented once it has been compiled. Given the dynamic nature of LSP and the importance of staying abreast of current developments in the subject field, open corpora are likely to be of more interest for LSP users.

Learner corpus: A learner corpus is one that contains texts written by learners of a foreign language. Such corpora can be usefully compared with corpora of texts written by native speakers. In this way, teachers, students or researchers can identify the types of errors made by language learners. Granger (1998) provides more details about learner corpora.

Are there tools for investigating corpora?

Once a corpus has been compiled, you can use corpus analysis tools to help with your investigations. Most corpus analysis tools come with two main features: a feature for generating word lists and a feature for generating concordances. We will introduce these tools here briefly so that you have some idea what they can do, but they will be examined in greater detail in Chapter 7.

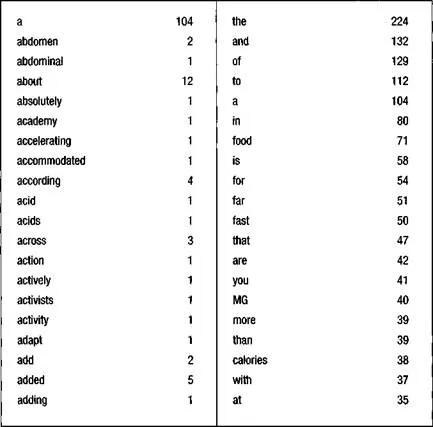

A word lister basically allows you to perform some simple statistical analyses on your corpus. For instance, it will calculate the total number of words in your corpus, which is referred to as the total number of ‘tokens’. It will also count how many times each individual word form appears; each different word in your corpus is known as a ‘type’. The words in the list can be sorted in different ways (e.g. in alphabetical order, in order of frequency) to help you find information more easily. Figure 1.1 shows two extracts from a word frequency list taken from a 5000-word corpus of newspaper articles about fast foods. The list on the left is sorted alphabetically while the one on the right is sorted in order of frequency.

A concordancer allows the user to see all the occurrences of a particular word in its immediate contexts. This information is typically displayed using a format known as keyword in context (KWIC), as illustrated in Figure 1.2. In a KWIC display, all the occurrences of the search pattern are lined up in the centre of the screen with a certain amount of context showing on either side. As with word lists, it is possible to sort concordances so that it becomes easier to identify patterns.

Why use corpora to investigate language?

Now that we understand what corpus linguistics is and how we can generally go about it, let us explore some of the reasons why we might want to use corpora to investigate language use. There are, of course, other types of resources that you can use to help you learn more about LSPs.

Figure 1.1 Extracts from a word frequency list sorted alphabetically and in order of frequency

For example, you have no doubt consulted numerous dictionaries, and you may also have consulted printed texts, or asked a subject field expert for help. You may even have relied on your intuition to guide you when choosing a term or putting together a sentence. All of these types of resources may provide you with some information, but as you will see, corpora can offer a number of benefits over other types of resources. This is not to say, of course, that corpora are perfect or that they contain all the answers. Nevertheless, we think you will find ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: Setting the scene

- Part 2: Corpus design, compilation and processing

- Part 3

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Working with Specialized Language by Lynne Bowker,Jennifer Pearson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.