This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As ICT continues to grow as a key resource in the classroom, this book helps students and teachers to get the best out of e-literature, with practical ideas for work schemes for children at all levels.

Len Unsworth draws together functional analyses of language and images and applies them to real-life classroom learning environments, developing pupils' understanding of 'text'. The main themes include:

- What kinds of literary narratives can be accessed electronically?

- How can language, pictures, sound and hypertext be analysed to highlight the story?

- How can digital technology enhance literary experiences through web-based 'book talk' and interaction with publishers' websites?

- How do computer games influence the reader/ player role in relation to how we understand stories?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access E-literature for Children by Len Unsworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Didattica generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Children’s literature and literacy in the electronic age

Introduction

The ways in which children and young people interact with literary texts are being profoundly influenced by the internet and the world wide web (www) as well as other aspects of contemporary Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). In fact, the impact of ICTs is changing the nature of literary texts and also generating new forms of literary narratives (Hunt, 2000; Locke and Andrews, 2004), including some video game narratives (Gee, 2003; Ledgerwood, 1999; Mackey, 1999; Zancanella et al., 2000). However, it is not the case that the literary interests of the digital multimedia world are replacing books as a presentation format for children’s literature (Dresang, 1999; Gee, 2003; Hunt, 2000). Rather, what we see emerging are strongly synergistic complementarities, where the story worlds of books are extended and enhanced by various forms of digital multimedia, and correspondingly, some types of digital narratives frequently have companion publications in book form. In Margaret Mackey’s (1994:15) words ‘Cross-media hybrids are every where.’ She points out that children come to school already used to making cross-media comparisons and judgements whether the stories are about Thomas the Tank Engine or Hamlet, and that

To talk about children’s literature, in the normal restricted sense of children’s novels, poems and picture-books, is to ignore the multi-media expertise of our children.

(Mackey, 1994:17)

However, 10 years later, although literature for children and young people maintains its significant role in state and national English curriculum documents, such documents are silent about literary narratives in the digital sphere (Locke and Andrews, 2004). There is also relatively little use of ICTs in teaching literary texts in schools, according to national studies in Australia (Durrant and Hargreaves, 1995; Lankshear et al., 2000). On the other hand, online and other digital media resources for working with literature in the classroom are burgeoning, access to appropriate computing facilities in schools in Western countries is becoming routine, and there is an emerging research literature dealing with the interface of ICTs, literature and literacy education (Jewitt, 2002; Locke and Andrews, 2004; Morgan, 2002; Morgan and Andrews, 1999). To bridge the gap between many students’ experience of literature in the digital world and their classroom experience, beginning teachers who have more familiarity with ICTs, as well as established teachers, who are less familiar with ICTs but have great expertise and experience in working with literature, need access to organizational, interpretive and pedagogic frameworks that will assist them in managing effective classroom programs using digital resources for developing literary understanding and literacy learning. The purpose of this book is to contribute to the development of these frameworks. This chapter provides an overview of key elements of the frameworks, which are then discussed in more detail in the subsequent chapters, with examples from online narratives, teaching resources and suggestions for teaching/learning activities. The first stage of the overview here deals with an organizational framework describing the articulation of conventional and computer-based literary narratives for children and adolescents. The second stage outlines interpretive frameworks addressing the increasingly integrative role of language and images in the construction of literary meanings in electronic and book formats. The third stage deals with pedagogic frameworks, beginning with the online contexts for developing understanding about different dimensions of literary experience, and then addressing the management of learning activities derived from such contexts in extended programs of classroom work.

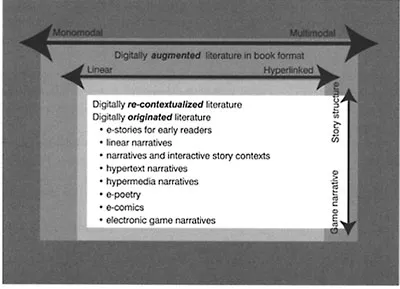

Describing the articulation of book and computer-based literary narratives

Here we are concerned with the relationships among literary materials on the web, on CD-ROMs and in books. From time to time in this book mention will be made of movie versions of various literary works and their availability as DVDs, but the focus will be online and CD resources. It is useful to think about the relationships among literary texts and digital media in terms of three main categories. The first refers to electronically augmented literary texts, or perhaps electronically augmented experience relating to literary texts. This category is concerned with literature that has been published in book format only, but the books are augmented with online resources that enhance and extend the story world of the book. This kind of augmentation is most frequently provided by the publishers and/or the authors themselves. Sometimes it involves information about the genesis of the story, further details of artefacts or additional information about characters, and sometimes it involves presentation of selections from the story in print or by the author, or someone else, reading a sample chapter or segment, to entice the potential reader to invest in the whole story. The ways in which books are augmented with such online enhancements are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

The second category of relationship among literary texts and digital media is the electronically re-contextualized literary text. In this category, literature that has been published in book form is re-published online or as a CD-ROM. The online republication takes a variety of forms. Many works that are now in the public domain because copyright laws no longer apply (usually because it is more than 50 or 70 years since the death of the author) have been transcribed or scanned and located in online digital libraries. The most widely known of these is the Gutenberg Project (http://gutenberg.net/), but there are many other such online libraries, including some specializing in books for children. These resources are detailed in Chapter 4. The scanned books contain the original images, but since copyright is not an issue, some other sites provide the texts of these stories with new images interpolated. These online versions of published books can be accessed free of charge. The second type of online version of published books is usually contemporary stories that are provided by publishers and can be downloaded at a cost. It is also possible, at a modest cost, to download audiofiles for many current titles, including classics like Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant (Wilde and Gallagher, 1995), as discussed in Chapter 7. Some books are also published as audio only CDs, such as Stephen Fry’s reading of the Harry Potter books, published by BBC Audio Books in the United Kingdom. But most CD-ROM versions of literary texts include images and text, which vary to a greater or lesser extent from those in the book versions. In some cases the images are static, simply transposed from page to screen. This is the case with The Paper Bag Princess (Munsch, 1994) for example. In other cases the original images from the book appear as animations on the CD as in The Polar Express (Van Allsburg, 1997). In this CD the animations activate automatically, but in others like The Little Prince (de Saint-Exupery, 2000b), the animations are controlled by the mouse ‘clicks’ of the viewer. In some cases novels for mature readers such as Of Mice and Men (Steinbeck, 1937; Steinbeck Series, 1996) have been re-presented as CD-ROM versions including images throughout. Literature re-contextualized as CD-ROM presentations is discussed in Chapter 4.

The third category relating literary narratives to digital format is the digitally originated literary text. These are stories that have been published in digital format only—on the web or CD-ROM. Relatively few such stories appear on CD-ROM. Some notable examples (James, 1999) such as Lulu’s Enchanted Book (Victor-Pujebet, n.d.) and Payuta and the Ice God (Ubisoft, n.d.) are discussed in Chapter 5. The great variety of literary narratives for children and adolescents published on the web can be categorized as follows:

- e-stories for early readers—these are texts which utilize audio combined with hyperlinks to support young children in learning to decode the printed text by providing models of oral reading of stories and frequently of the pronunciation of individual words;

- linear e-narratives—these are essentially the same kinds of story presentations which are found in books, frequently illustrated, but presented on a computer screen;

- e-narratives and interactive story contexts—the presentation of these stories is very similar to that of linear e-narratives, however the story context is often elaborated by access to separate information about characters, story setting in the form of maps, and links to factual information and/or other stories. In some examples it is possible to access this kind of contextual information while reading the story;

- hypertext narratives—although frequently making use of a range of different types of hyperlinks, these stories are distinguished by their focus on text, to the almost entire exclusion of images;

- hypermedia narratives—these stories use a range of hyperlinks involving text and images, often in combination.

To this list must be added some types of video games, defined in Chapter 6 as electronic game narratives. The development of new forms of literary narrative in the context of electronic games has been a focus of a recent study (Ledgerwood, 1999; Mackey, 1999; Murray, 1998; Zancanella et al., 2000). Examples of these forms of e-fiction as well as e-poetry and e-comics are discussed in Chapter 5, and electronic game narratives are discussed in Chapter 6.

All three of the above categories relating literature to the resources of the web and CD-ROM technology vary from monomodal (print only) to multimodal presentation, involving print, images and sound. The digitally re-contextualized and digitally originated e-fiction also vary along the continua of linear to hyperlinked and from conventional story structure to innovative game narratives. The organisational framework describing the articulation of book and computer-based literary texts for children and adolescents is summarized in Figure 1.1.

Interpreting the joint role of images and text in constructing literary narrative

Over the last decade images have become increasingly prominent in many different types of texts in paper and electronic media. Recent publications of popular fiction and new editions of classic literature are now frequently richly illustrated. This can be seen in novels such as Terry Pratchett’s Discworld Fable The Last Hero illustrated by Paul Kidby (2001), and the edition of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings illustrated by Alan Lee (2002), as well as in illustrated novels for young readers such as Isobelle Carmody’s Dreamwalker,illustrated by Steve Woolman (2001). The kinds of images and their contribution to overall meaning vary with the type of narrative. However, overwhelmingly, both the information in images and their effects on readers are far from redundant or peripheral embellishments to the print. Because images are used increasingly, and in a complementary role to the verbal text, it is now inadequate to consider reading simply as processing print. The need to redefine literacy and literacy pedagogy in the light of the increasing influence of images is widely advocated in the international literature (Andrews, 2004a, 2004b; Cope and Kalantzis, 2000; Goodman and Graddol, 1996; Lemke, 1998a, 1998b; Rassool, 1999), drawing attention to ‘the blurring of relations between verbal and visual media of textuality’ (Richards, 2001). Writing about Books for Youth in a Digital Age, Dresang noted that:

Figure 1.1 Describing the articulation of book and computer-based literature

In the graphically oriented, digital, multimedia world, the distinction between pictures and words has become less and less certain.

(Dresang, 1999:21)

and that

In order to understand the role of print in the digital age, it is essential to have a solid grasp of the growing integrative relationship of print and graphics.

(Dresang, 1999:22)

There is also a strong consensus that the knowledge readers need to have about how images and text make meanings, both independently and interactively, requires a metalanguage, or a grammar, for describing these meaning-making resources.

In the book Tellers, Tales and Texts (Hodges et al., 2000) Bearne noted that:

Once readers develop a metalanguage through which to talk about texts they are in a position to say—and think—even more.

(Bearne, 2000:148)

And earlier in his classic study, Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books, Perry Nodelman noted that the interpretation of the narrative role of images in children’s books would be enhanced by

the possibility of a system underlying visual communication that is something like a grammar—something like the system of relationships and contexts that makes verbal communication possible.

(Nodelman, 1988:ix)

The development of systemic functional linguistics (SFL) (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2001; Martin, 1992; Martin and Rose, 2003; Matthiessen, 1995) and its application to work with literature for children (Austin, 1993; Hasan, 1985; Knowles and Malmkjaer, 1996; Stephens, 1994; Williams, 2000), as well as the extrapolation from SFL of a grammar of visual design for reading images by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) and its application to work with chldren’s literature (Lewis, 2001; Stephens, 2000; Unsworth, 2001; Unsworth and Wheeler, 2002; Williams, 1998) has brought Nodelman’s earlier wishes to reality. The interpretive frameworks offered by this work, and their use in understanding the role of images and text in constructing meanings in literary narrative, will be introduced in Chapter 2.

Towards a pedagogic framework for e-literature and classroom literacy learning

The interpretive tools provided by functional descriptions of verbal and visual grammar introduced in Chapter 2 enable teachers and students to read literary texts grammatically, so that they are able to read the ‘constructedness’ of the texts, simultaneously focusing on the ‘what’ of the story and the ‘how’ of its verbal and visual construction. Throughout this book, suggestions for learning experiences designed to support young readers in developing this interpretive, grammatical reading will be introduced in the context of the foci of the subsequent chapters—classic and contemporary stories online, emerging literary hypertext for children and electronic game narratives. This perspective on developing children’s literary understanding and concomitant literacy development is a particular innovative feature of the research reported in this book and does not currently find explicit expression in the online resources for using e-literature in the English curriculum. Nevertheless, there are richly inspiring online resources for extending children’s literary experience, and the approach in this book is to co-opt such resources for infusion with the above perspective forming a basis for enhancing chil...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Children’s literature and literacy in the electronic age

- Chapter 2: Describing how images and text make meanings in e-literature

- Chapter 3: Learning through web contexts of book-based literary narratives

- Chapter 4: Classic and contemporary children’s literature in electronic formats

- Chapter 5: Emerging digital narratives and hyperfiction for children and adolescents

- Chapter 6: Electronic game narratives Resources for literacy and literary development

- Chapter 7: Practical programs using e-literature in classroom units of work

- References