![]()

Chapter 1

Questions of Evidence

To understand archaeology as a discipline, the evidence that it produces and the interpretations it puts forward, we need to begin with a matter that divides archaeologists from historians – the use of evidence and the combination of evidence texts and archaeological data. These are subjects that can cause scholars to get a little hot under the collar. Some have even suggested that combining these forms of evidence is only desirable after both sets of evidence have been studied independently (see Allison 2001). Part of the problem is caused by a belief that texts surviving from antiquity can be regarded or treated as data. What I wish to do for much of this chapter is to examine how texts need to be read, treated and analysed in the context of their production and consumption – i.e. the time when they were written and read – and how the time of production of a text reveals a temporal point that can be seen to be a context, or a point from which we may integrate the content with the archaeological record of the same time.

The problems raised in discussion of how we read and combine texts and material evidence may be embedded within the institutional power struggles that established the modern discipline of archaeology – that will be a focus of Chapter 2 of this book, but needs to be introduced here. To create a modern discipline of archaeology in the mid–late 20th century, it was seen as essential for archaeology to assert its place as much more than the ‘handmaiden of history’. In so doing the discipline developed an emphasis on the independent study of material culture mostly without reference, if possible, to texts – the province of historians. The teaching of historical archaeology in UK universities at times appears to feature a deliberate attempt to avoid an engagement with textual evidence, and to focus solely on the analysis of archaeological data. This may be pragmatic; after all few single honours archaeology undergraduates will be versed in textual analysis, but any joint honours student taking ancient history will find the avoidance of textual evidence baffling, and will be even more confused when their use of this evidence in essays is not rewarded. As Anders Andrén (1998) stresses, there are archaeologists who do not wish to engage with any textual sources and instead derive their conclusions entirely from the archaeological data (see examples discussed in Sauer 2004a). There are also some archaeologists who still wish to use the archaeological record to ‘prove’ that the textual evidence is simply wrong or a misrepresentation of the past (Allison 2001). These approaches are similar to those of the historian, who sees no value in archaeology and suggests that archaeology can only show you what you knew already from your texts – all such practitioners are missing the point. As Andrén (1998:4) points out, the two types of evidence, texts and artefacts, are two different human discourses. Relating these together can be straightforward or down-right impossible. The key to success in this area is keeping a wary eye on the contexts, dates and type of materials that are being integrated from these two quite different discourses.

Part of the problem for ancient historians in dealing with archaeology is that we have read the texts that seem to describe the places that survived as archaeology. We cannot disaggregate or completely lose our knowledge of texts prior to evaluating a piece of archaeological evidence. Nor would such a process be desirable, since texts can aid the development of archaeological knowledge. For example, in approaching the archaeology of King Herod’s new city at Caesarea most scholars will have read Josephus’ description of the new city (Josephus Wars 410–13; Antiquities 15.331–38). Caesarea, like Augustus’ Rome, was rebuilt in marble and its buildings were seen by Josephus to have been worthy of the person from whom the city gained its name, Caesar (Augustus). Josephus’ harbour at Caesarea is the size of the Piraeus in Athens. What we see here is a rhetoric that praises the city and its builder/monarch (compare the later writer Menander Rhetor’s How to Praise a City). However, what can be identified in the archaeological record coincides with the rhetorical description of the harbour itself, but there are monuments within Josephus’ text that have yet to be identified (see Vann 1992). This is an example of a text aiding archaeology to formulate a strategy for investigating a site – Josephus’ two accounts aid the fieldwork on site. Importantly, in this example, the texts of Josephus and the archaeological site are broadly contemporary. In effect, both the text and the archaeological data are derived from a very similar (if not congruent) context: the 1st century AD – hence in this example the convergence of the two sets of source material is less problematic.

Texts and archaeology in context

The relationship between texts referring to historical phenomena and the archaeological investigation of sites or even landscapes associated with those phenomena becomes far more complex when the historical writers are distanced by years or even centuries from the events themselves. Here, I wish to illustrate how the inappropriate reading of texts and archaeological evidence from different contexts can cause a disjuncture in the evidence and reduce the value of archaeology aiding historical analysis. Most students of Roman history will come across the land reform of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC. The basis of much of our knowledge of the motivations for these reforms comes from passages in the biography of this man by Plutarch (c. AD 50–120), Tiberius Gracchus, and Appian’s historical narrative: The Civil Wars. Interestingly, Appian (c. AD 95–165) was an author who inspired Karl Marx, and with good reason, because he offers the modern reader some of the rare instances of socio-economic analysis that survive from antiquity. To quote some of the text to provide a flavour of Appian’s work:

The rich getting possession of the greater part of the undistributed lands (ager publicus), and emboldened by the lapse of time to believe that they would never be dispossessed, absorbing adjacent strips and their poor neighbours’ allocations, partly by purchase under persuasion and partly by force, came to cultivate vast tracts instead of single estates, using slaves as labourers and herdsmen, lest free labourers should be drawn from agriculture into the army. At the same time the ownership of slaves brought them great gain from the multitude of their progeny, who increased because they were exempt from military service. Thus certain powerful men became extremely rich and the race of slaves multiplied throughout the country, while the Italian people dwindled in numbers and strength, being oppressed by debt, taxes and military service. If they had any respite from these evils, they passed their time in idleness, because the land was held by the rich, who employed slaves instead of freemen as cultivators.

(Appian Civil Wars 1.7, Loeb translation).

What is difficult to see in this superb piece of persuasive and coherent analysis is the question of when all this was occurring. Appian in some ways suggests that it refers to the time at which the Lex Licinia was passed in 367 BC and in other ways suggests the process was also occurring closer to 133 BC (App. BC 1.8). Perhaps, what is most logical is that Appian is suggesting that the process took place prior to 367 BC and over the 234 years since 367 BC and the passing of the Lex Licinia. It is a long-term phenomenon that would seem to lead to Tiberius Gracchus’ legislation. In contrast, Plutarch (TG 8), suggests that on a journey to Spain through Etruria, Tiberius Gracchus saw a large deserted landscape populated only by slave herdsmen and it was the end result of the long-term process that inspired his legislation. Again the passage is worth quoting:

When the rich began to outbid the poor by offering higher rentals, a law was passed [the Lex Licinia presumably] which forbade any one individual holding more than 500 iugera of land. For a while this law restrained the greed of the rich and helped the poor … But after a time the rich men in each neighbourhood by using the names of fictitious tenants, contrived to transfer many of these holdings to themselves, and finally they openly took possession of the greater part of the land under their own names … The result was a rapid decline of the class of free small-holders all over Italy, their place being taken by gangs of foreign slaves, whom the rich employed to cultivate the estates from which they had driven the free citizens … His brother Gaius Gracchus has written in a political pamphlet that while Tiberius was travelling through Etruria on his way to Numantia, he saw for himself how the country had been deserted by its native inhabitants, and how those who tilled the soil or tended the flocks were barbarian slaves introduced from abroad and it was this experience which inspired the policy.

(Plutarch Life of Tiberius Gracchus 8, Loeb translation)

Plutarch, unlike Appian, is linking the result of the process to a specific instance in the life of Tiberius Gracchus. Obviously, we are dealing with two writers who are shaping their material for consumption more than two centuries after the legislation of Tiberius Gracchus. The authors are producing literature at a distance from the events themselves, rather than documenting observations contemporary with the legislation of 133 BC. Is it possible for archaeology to prove or disprove the veracity of their reporting? Can archaeology help us untangle what was the author’s invention (inventio) or the invented tradition of the Gracchan legislation associated with Roman society in the late 1st and 2nd centuries AD and what can be seen as the preservation of the ‘facts’ from the 2nd century BC?

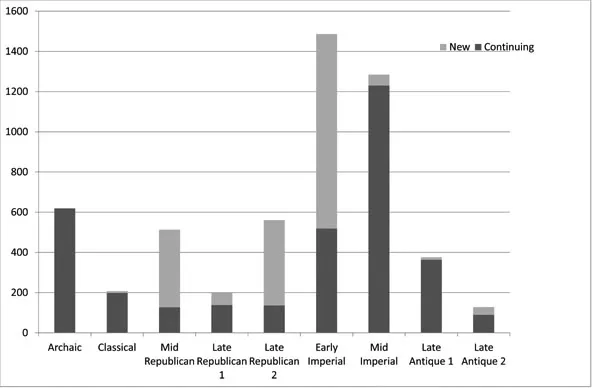

To provide answers to these questions, we need to provide compatible archaeological data. The large-scale landscape surveys in South Etruria and the Middle Tiber Valley identified sites dated by the evidence of pottery picked in the field (see Chapter 4 for further discussion of survey evidence). What we find associated with the 2nd century BC is a populated landscape quite unlike that described by Plutarch in the passage above (Lloyd 1986 based on Potter 1979). Perhaps we should not be surprised at a disjuncture of the two types of evidence. Plutarch reports a process via the personal recall of the subject of his biography. More importantly, his source – a pamphlet of Gaius Gracchus – served a rhetorical and political purpose and was far from objective. It was a piece of propaganda and as such we should expect exaggeration or a rather economical approach to the ideal that we associate with the truth. In other words, to expect a replication of this text on the ground is misguided and archaeology aids us in seeing our textual sources for what they are: in the case of Plutarch, literary construction of a life of a man from the past that places a firm emphasis on the subject of the biography and his experiences as sources for his political motivations. We also need to recognize that archaeological evidence cannot be precisely dated to coincide with the decade associated with 133 BC. What archaeology is far better at doing is providing us with data for the long-term change that might be seen to coincide with the processes that Appian and Plutarch seem to be referring to from the 4th to the 2nd centuries BC. The recent reassessment, including substantial re-dating of the pottery, has produced an overall pattern of long-term change in the settlement patterns of the Middle Tiber Valley up to approximately 50 miles north of Rome, and has produced a powerful model of landscape continuity over the long term. The data are presented in Figure 1.1. What we see in black are sites that have continuity from one broad period to another and in grey are the new sites that appear during each broad period. Mapping this data onto the texts of Plutarch and Appian demonstrates some convergence between the two types of evidence. In the period c. 500–350 BC (Classical in Figure 1.1), there is a marked drop in the number of sites from the earlier period – this might have some convergence with the need to pass the Lex Licinia that may have been behind the overall expansion in the number of sites in the Mid-Republican period down to the middle of the 3rd century. Following this period, Late Republican 1 (down to the end of the 2nd century BC), there was a contraction in the number of sites – perhaps coinciding with some of the conditions suggested by Plutarch and Appian (see Patterson et al 2004 for details and discussion). However, there are other striking questions of the data-set reproduced in Figure 1.1. Not least, the massive expansion of the number of settlements in the region in the Early Imperial period that is sustained through to c.250 AD. This was the stable landscape seen by Plutarch and Appian under the emperors and is the point of comparison for their discussion of the Agrarian legislation of the past – it was a landscape whose population had expanded under the empire and had become stable (see Chapter 4 for further discussion). Looking back into the past, Appian and Plutarch created a landscape of chaos caused by the greed of the rich and the presence of slavery. What archaeology does here is provide us with an understanding of the landscape of these two authors’ present time and relates it back to the earlier phases of settlement geography. Seen in this context, Appian and Plutarch were making sense of the cultural memories of an Italian landscape that was fundamentally different from what they themselves experienced (see Witcher 2006a on the subject of memory and field survey).

Figure 1.1 Sites in the Tiber Valley over time (provided by Rob Witcher)

I feel this aspect, that the textual sources are shaped by their time of production, needs to be re-emphasized once again with reference to Plutarch on the subject of Gaius Gracchus. What presents Romanists with a greater challenge than historical archaeologists working on later periods is the nature of the textual sources. These are inherently, for the most part, produced by a literary elite producing narratives in various genres – often at considerable distance from the historical phenomena that they are attempting to represent. In reading these texts, we need to be well aware of the context of production and recognize that the texts may actually say rather more about the author’s time than about the activities of those in the past that are represented in their texts (Andrén 1998: 147; Scott 1993 for discussion). Hence, the passages of Appian and Plutarch quoted earlier in this chapter represent a view of Greek writers under the rule of the Roman emperors examining the flaws of the Roman Republic. There is an implicit comparison between the social divisions and greed of the rich of the Republic with the contemporary efforts of the emperors and the elite in Italy to support the poor via the alimenta (Laurence 1999b: 49–51). The positive values found in these texts associated with the Gracchi written by Plutarch engage with a rhetoric used to praise the emperor:

He [Gaius Gracchus] also introduced legislation which provided for the founding of colonies, the construction of roads, and the establishment of public granaries. He himself acted as director and supervisor of every project and never flagged for a moment in the execution of all these elaborate undertakings. On the contrary, he carried out each of them with extraordinary speed and power of application, as if each concern were the only one he had to manage, so that even those who disliked and feared him most were amazed at his efficiency and his capacity to carry through every enterprise to which he set his hand. As for the people, the very sight of Gaius never failed to impress them, as they watched him attended by a host of contractors, craftsmen, ambassadors, magistrates, soldiers, and men of letters, all of whom he handled with a courteous ease which enabled him to show kindness to all his associates without sacrificing his dignity, and to give every man consideration that was his due.

(Plutarch Life of Gaius Gracchus 6, Loeb translation)

When Plutarch describes the landscape created by Gaius Gracchus, he is not representing the landscape of the past, but instead is describing the contemporary landscape of Italy in the late 1st and early 2nd century, which we can identify in the archaeological record and again engages with the praise of emperors as road builders (see, for example, Statius Silvae 1.5). The passage is worth quoting:

The construction of roads was the task into which he threw himself most enthusiastically, and he took great pains to ensure that these should be graceful and beautiful as well as useful. His roads were planned to run right across the country in a straight line, part of the surface consisting of dressed stone and part of trampled down gravel. Depressions were filled up, watercourses or ravines that crossed the line of the road were bridged, and both sides of the road were levelled or embanked to the same height, so that the whole of the work presented a beautiful and symmetrical appearance. Besides this he had every road measured in miles … and st...