![]()

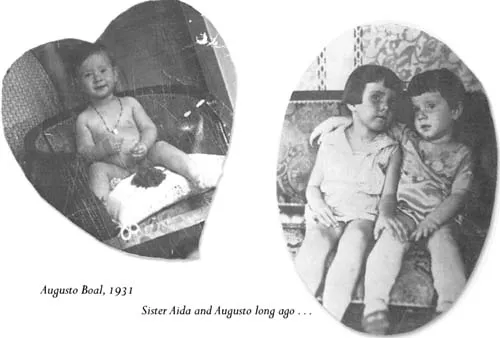

a long time ago, I was a boy

Three children crying

Silling on the bridge at the entrame to my house one Sunday night. I cried and cried. I was 9 years old, a sensitive and emotional age.

That Sunday lunch had left an indelible mark on mv life. Il was a savage episode. I can remember the characters of that gory story quite clearly, l-ach lime I cast my mind back I recall other forgotten details, and mv eyes threaten tears.

On that Sunday, my sadness was provoked by a painful ethical question to do with individual responsibility. For a child of 9. ethical questions are spectacularly important. Was I, or was I not, the person responsible for the savagery? Nine years old, and alreadv so responsible!

We had manv animals in the backyard of our house. When the chickencoop was full, it was as overcrowded as a Brazilian prison. We frequently

ate chicken stew, often roast chicken, and occasionally coq au vin. More rarely, we ate domestic duck and sometimes wild mallard.

The feathered ones spent. their lives imprisoned in an overcrowded chicken-coop, at the end of the yard, with the right to roan about scratching for worms and exercising their muscles. The chickens’ playtime began in the morning and ended when the sun set, when they would politely and voluntarily return to their roost! Our dog, Leão (Lion) helped to drive the hens and their partners back to jail.

The yard wvas large, with room for bulkier beasts as well. When ihr goats at the market looked well-proportioned and friendly, my parents would buy a billy and two or three nannies. Soon there would be kids, inevitably. Occasionally we kept pies.

This modest zoological garden had, to mychild's eyes, a sense of tragic pastime, because it was also a gastronomical garden. I became attached to these creatures, I liked to play with them, to baptise them — I even engaged the cocks, hens and kids in long and intelligent conversations, I spoke in Portuguese, and each of them spoke in their own natural language which translated, trying (like any translator!) to improve the style and to clarify any misunderstandings provoked by the exuberance of their personalities.

We appeared to be friends: we weren't. The truth tormented me: I lived in tbe big house, destined for a brilliant university future, I would be a‘Doctor’. They, on the other hand, lived on Death Row, destined for the cooking pot, the oven, the stove and the spit. Even the corn and the other rations we gave them, in our generosity — and for which they, in their naivety, were grateful — had this culinary intent, Our backyard was a huge concentration camp: all the guests had the date of their death fixed. Only I would live for ever, for all my life! True friendship cannot exist between two individuals when one is eternal and the other perishable.

Playing with the creatures at the end of the day, I felt like the priests charged with administering the last rites to the condemned, in the prisons of Alcatraz, or Devil's Island. I frequently suffered from a restless insomnia, wondering which would be condemned the following morning; I would run through each animal's features in my mind. I felt a tremendous relief when, on my return from school in the afternoon, I found that my favourite chickens and ducks and drakes and goats were still alive.

It was only the pigs I didn't care for. Nor they for me: there was a certain reciprocal antipathy, verging on hostility, between me and the pigs, even the youngest ones. But although I had no particular fondness for any

Augusto, Albertino (brother), Albertina (mother), José Augusto (father), Augusta (sister), Aida (sister)

of the pigs, it was they who moved me to pity the most. Because they refused to die! They fought bravely, they cried out, horrifying the neighbourhood with their vociferous struggles — and managing to secure only the futile solidarity of the other animals, impotent companions in the same misfortune. None would escape its tragic destiny, come its allotted hour. of the pigs, it was they who moved me to pity the most. Because they refused to die! They fought bravely, they cried out, horrifying the neighbourhood with their vociferous struggles — and managing to secure only the futile solidarity ofthe other animals, impotent companions in the same misfortune. None would escape its tragic destiny, come its allotted hour.

The death of a pig was a hideous spectacle: blood spitting like a fine London rain, squeals, uproar in the chicken-coop, and a difficult struggle with the knife. Cousins and friends would come to help: it was not ajob for one man. From the moment of the ‘catch’, it was a dramatic and unequal combat. The executioners approached the pig, which emitted a groan, hoarse and nasal. Then the rest of the porcine family came out in solidarity in terror and panic. The brutes seized the pig and tied its trotters in pairs, while the principal executioner sharpened the knife. At the sight of the knife, the pig became aware of its tragic destiny. By intuition or instinct, it knew the true intentions of the blade and vociferated in anticipation.

The knife would puncture the swinish throat, and the first gush of blood would spurt out, whipping around like an untended hose, soaking everything around it. Meanwhile the c eophonie cries and clamour of the other animals redoubled. The struggle — armed on one side only — would last half an hour, a whole hour, an hour and a half, or more. That is when things went well, from the executioner's point of view But it could be worse: the intrepid pig might free itself from its bonds, break loose from its captors, and run screaming around the yard, shedding blood everywhere. On such occasions, the women would close the windows and observe the proceedings from behind the glass, while we children would spectate from a distance, as the men closed in on the animal with ropes and chains and, in uses of extreme necessity, a sharp axe destined for its head.

One day a 300-kilo pig, whose death had been planned as meticulously as a military campaign, hurled itself against the chicken coop in its death throes, ripping open the fence and freeing the prisoners. The demented fowl then used their wings for the first time in their lives and Ilew like songbirds out of the yard and into neighbouring gardens. I didn't even know that chickens could fly! We can all fly! itjust depends how urgent it is. Some neighbours kindly returned the gallinaceous escapees. Others only gave up the creatures when my father threatened to call the police.

Once the pig was dead, the corpse was gutted and quartered in sombre silence. Everyone felt guilty as they cut the porcine fat into small pieces for crackling, with the cars, knees, tail and snout kept for feiijoadas, and every part of the body destined for a different earthenware pot and its own seasoning. After the assassination, the pig's executioners had to bathe from head to footin soapy water, and apply rice powder to their armpits, talc to their ankles and eau-de-cologne to their clothes, before they were able to return to civilisation.

Chickens were strangled with less spectacle — it was a routine event. The maid was charged with the sacrifice. After a couple of deceptive little caresses, she clasped hold of the victim's neck with a single flourish and wrung it. Then a small knife would appear as if from nowhere, and be used to cut the victim's head off. Blood poured out and was placed in a large jar: this gave colour to the cabidela.

(My mother only tried to kill a chicken once. It was a disaster. In the middle of the bloody business she took pity on the bird, which then, with its neck half-severed, ran into and around the drawing-room, spattering the furniture with blood. Never again!)

Rabbits were murdered with ease: a sharp blow at the back of the head and that was it: dead. But then the ugly part would begin. The white neck would be cut and the skin stripped down to the knees, and the body hung up naked, skin and fur still attached to its lower legs, like Finnish boots in midwinter. The skin was treated with chemical products and made into rugs. The skinned body was thrown into an iron pot and braised in butter, plenty of garlic, onion, chilli and sweet pepper, tomato, salt and flour.

And what of the goats? I have never seen a goat die. In my house, when the death of a goat was decreed, the execution would take place on a Saturday morning, when I was still at school, and the body would be laid in state in the fridge for the rest ofthe day and one night, in a garlic marinade. We ate goat only on certain special Sundays, for lunch. Before I went off to school early in the morning, I would see the frisky goats, gambolling playfully; by the time I saw them in the afternoon, they were already marinaded in garlic and stuffed with bread, tripe and olives. I was spared their martyrdom.

It was a goat that was responsible for my first moral dilemma. That goat was called Chibuco. I do not know whether it begins with an ‘x’ or ‘ch’:1 this is the first time I have written his adored and saudoso name.

He was born at home, the son of a nanny-goat for whom I nurtured a certain affection, and a billy who looked cross, like all billies, but who I admired for being genteel, elegant, affable, respectful, of good heart which is not the norm in your common-or-garden goat. I ended up adopting Chibuco, who became my favourite animal.

Our friendship grew with time, and my family was amazed. Chibuco played with me and obeyed my orders, understanding words which not even a stunned Leão (my dog) would comprehend, thhough dogs are more intelligent than goats — they have a much higher IQ.

Chibuco was the greatest! He ran, he did somersaults — extremely rare in a goat — and even (uniquely, I believe) leapt over ropes: without great dexterity, it is true, but leap he did.Yes ladies and gentlemen, he leapt over ropes. I tied a rope to the basement railings in the yard, and Chibuco leapt over it, obeying my orders. A rope-leaping goat, every child's dream.

When I think about it, Chibuco was my first actor. I became a theatre director because of a goat. I was very authoritarian, it is true, as immature directors are. But I began my career in theatre with Chibuco: I directed goat shows, without ever consulting or swapping ideas with my cast. Only later did I learn the joys of team work.

Boys, my friends — and girls, sort of friends — came to see the prodigy: Chibuco leaping over a rope, Chibuco skipping on the pavement, Chibuco affectionately butting the trees and people's legs. And me directing, proudly When I could think of no other instruction, I would tell Chibuco to imitate a clog. And Chibuco, an excellent actor, would roll over on his back in imitation of Leão.

Everyone liked it: dona Angelina, a widow living alone in the house next door, would abandon her household duties and come to catch the act. Even Aunt Lúcia, already a wizened little old lady when I knew her also liked to watch through her round glasses.

‘He is like a child …so innocent…’ Lucia would say.

'That is not a normal goat… Goats don't do that sort of thing…. This is more in the way of witchcraft…’ Angelina diagnosed.

Chibuco, happy Chibuco, even smiled when I called him — or almost. And when I sent him away, he was sad, almost wept, like a little lamb — almost.There was a solid friendship between boy and goat.This friendship grew with time, along with Chibuco's horns, which lengtbened with age. Chibuco emancipated himself from his mother goat. He transformed himself into an elegant adolescent goat, entering confidently into adult Wc, as proud of himself as a preening peacock.

Until, one day, tragedy struck.With no ill will, perverse or treacherous intent, but rather out of an undisciplined audacity, Chibuco went too far. Hie overstepped the agreed mark and showed me a lack of respect by ramming his horns right into my chest. Blood flowed.

Chibuco, more astonished than I, looked at me as if to ask forgiveness, without finding the right words. He approached, to kiss my wound better — I imagine— but I was so disgusted at being butted and with the blood that I rejected him with a cold and haughty glare. And decided, as a punitive measure: ‘I'm going to tell my Mum about this.’

That was my tragic mistake, the first of the tragic mistakes I have made in my life. First, my mother ...