- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Political Process

About this book

American Political Process examines both the formal institutions of government and organizations such as political parties and pressure groups. It analyzes how these bodies interact in the making of public policy in the United States in order to provide an understanding of contemporary American politics. The seventh edition has been thoroughly updated and revised with entirely new material on:

- the 2000 Presidential election and George W. Bush's presidency

- the September 11th attacks and the 'War on Terrorism'

- the 2002 mid-term elections

- controversial issues such as abortion and gun control.

Each chapter includes a variety of useful tables and diagrams, suggestions for further reading and relevant websites and a glossary of key terms. Written with admirable clarity, this is the ideal textbook for students of American politics and society.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The framework of American politics

There have been many attempts to find a suitable definition of politics, but most people seem to agree that it is an activity that is related to the governing of a society. David Easton believes that politics is the ‘activity of trying to influence the direction of social life and public policy’,1 and he emphasises that politics is not merely a struggle for power, but that it is related to the goals and direction of a society. The United States is usually described as a ‘liberal democracy’ and in such societies, where freedom of expression and association are encouraged, there is a more open and active display of political activity than in the closed autocratic systems within which governments do not allow groups to canvass support for alternative policies. As a pluralist society, America has thousands of different factions who wish to promote their own interests and objectives, and the study of American politics can therefore be seen as an examination of the continuous process of groups competing to influence the formal institutions of government in order that official policies reflect their preferences and goals.

The people of the United States

Any consideration of American politics should start with the people of the United States who as individuals and groups affect and are affected by the policies of government. The 2000 census counted 281.4 million people, making the United States one of the world’s largest nations in population terms. In 1800 there were only five million people but in the two centuries since then a vast expansion has taken place, with the population almost quadrupling in the twentieth century alone (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Population growth in the United States 1790–2000

Immigration was the major factor in explaining the tremendous growth in the American population. The United States is, in the words of John F. Kennedy ‘a nation of immigrants’ since, with the exception of the American Indians, the people of America are the descendants of immigrants. The settlers who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620 were religious fugitives from Europe, and the early colonists had both a Protestant background and tradition of individualism and resistance to authority. The ‘WASPs’ (White AngloSaxon Protestants) are still the dominant group in American society today in terms of holding positions of power and responsibility, even though they are now a minority numerically. America’s heterogeneity and diversity of ethnic groups arose initially from the ‘open-door’ policy of immigration in the nineteenth century. From 1815 to 1914 there were over 30 million newcomers to the country; in the first part of the century they sailed mainly from Britain, Ireland and Germany, but by 1900 over a third were arriving from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Fears and hostility among the established population were aroused as masses of people, many poverty-stricken and speaking strange tongues, arrived at ports on the Eastern seaboard, and after the First World War restrictions on entry were introduced. In the 1920s quotas were fixed for each nationality, but as the system favoured Northern Europeans, critics charged that it was based on racial prejudice. In 1965 a new system was adopted and, as amended in 1976 and 1980, an annual limit was established. Preference was given to family members of US residents. The main impact was to reduce the flow from Northern Europe and to markedly increase the numbers from Asia (see Table 1.2).

The main motivation to come to America for the majority of immigrants was, and still is, a desire to seek a better life and standard of living than they could find in their own countries. Stories began to spread about the opportunities in America and were particularly attractive to those living in rigidly stratified European societies, where there was little hope of personal improvement. Some people fled from the autocratic governments in Eastern Europe to find political or religious freedom in America, while the development of cheaper steam transport made the journey a practical, if still dangerous, proposition.

Immigrants tended to settle in almost self-contained communities within the Eastern cities and they retained their own languages, dress and customs. Gradually over a couple of generations these groups became thoroughly assimilated into American society, while at the same time developing their own political leaders and remaining aware and proud of their ethnic origins. Although at various times there was tension and even violence, in broader perspective it is remarkable that so many millions of people were able to come from so many diverse backgrounds without more social and political instability. America has often been called for this reason ‘the melting-pot society’ although in recent times it has become fashionable to see the country as a mosaic with minority groups retaining their own identities and cultures while being part of the nation as a whole.

Table 1.2 Immigrants to the United States 1820–2000

Following legislation in 1980 almost two million refugees were admitted as permanent residents from countries such as the former Soviet Union, Vietnam, Cambodia and Cuba.

In 1990 Congress passed a major new immigration law which increased the total number of visas available, permitted more European entrants and gave priority to people with particular skills. As a result America experienced its second great wave of legal immigration: the 1990s saw more immigrants coming to the United States than any other decade in American history.2 By the beginning of the twenty-first century the country was considerably more diverse than it was even in 1990.

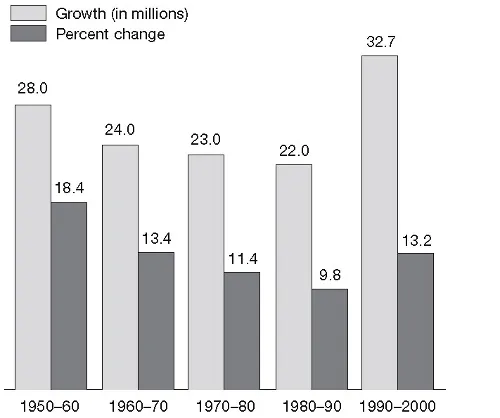

Figure 1.1 US Population Growth 1950–60 to 1990–2000

Source: ‘Population Change and Distribution 1990 to 2000’, Census 2000 Brief, US Census Bureau, April 2001.

Between 1860 and 1920 the proportion of the population that had been born outside the United States ranged from 13 to 15 per cent, reflecting the large-scale immigration from Europe. The 2000 census showed that the percentage of residents who were foreignborn had risen to 11.1 per cent (31.1 million) compared with 4.7 per cent in the 1970 count. More than half of the new arrivals, 51.7 per cent, came from Latin America, with 8.2 million from Asia and only 4.9 million or 15.8 per cent from Europe. As a result of this immigration there has been a marked increase in the number of people of five years and over who spoke a language other than English at home: 47 million in 2000 compared with 31.8 million in 1990. Of these, 21.3 million reported that they spoke English less than ‘very well’. Almost 60 per cent of those not speaking English at home spoke Spanish.3

By 1996 there were approximately five million illegal aliens residing in the United States4 with around 300,000 more arriving each year, mostly across the long land border with Mexico. Legislation passed in 1986 and 1996 has attempted to deal with this problem by increasing border patrols, speeding up detention and deportation procedures and improving methods of identifying illegal immigrants in the workplace, while also offering amnesty to around two million ‘undocumented’ immigrants who took up the opportunity to gain legal residency. Many observers believe that restrictionist measures are doomed to failure unless accompanied by a national database and the requirement that employers verify the legal status of every job applicant – moves that have been resisted by both business and civil liberties lobbies. While many Americans have shown their resentment at the mounting cost to the taxpayer of illegal immigration (for example, in California in 1994 voters passed a direct democracy measure, later declared unconstitutional by the courts, denying public services to illegal aliens), a growing coalition of politicians, business and trade union leaders have supported proposals which would allow some longstanding illegal immigrants to apply to become legal residents of the United States. Both Republican and Democratic leaders, conscious of the growing importance of Hispanic voters, were promoting such legislation in the 107th Congress (2001–2). Following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, DC on 11 September 2001 there were also demands for tighter security at US borders, an overhaul of the visa system to enable the authorities to keep track of individuals admitted legally to the country and a thorough reorganisation of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

There has also been a vigorous debate as to whether there should also be a substantial tightening of restrictions on legal immigration or further liberalisation of the regulations. Some politicians and business leaders continue to argue that immigration helps fuel economic growth and fills jobs ranging from unskilled agricultural work to computer engineer positions which too few Americans are willing, or able, to do. Some also believe that America has an historic mission and duty to be open to people seeking opportunities denied to them at home. However, there has also been criticism about the impact of immigration on the availability of jobs and the wage levels available to American citizens, and concern has been expressed that many of the new wave of entrants are not being effectively assimilated into society and that this will have worrying implications for the future stability of the nation.5 Some observers have gone as far as to suggest that there is a danger of ‘Balkanisation’ with the erosion of a common culture and language leading to the fragmentation and eventual disintegration of the United States.6 This has led to attacks on the development of multiculturalism and bilingualism, with a growing movement demanding that English be named as the country’s official language. In 1998 Californians voted to abolish bilingual education in the state’s schools and required that all classes be taught in English with non-English speaking pupils being given intensive courses in the language.

One section of American society that has not been integrated so easily has been the African-American or black community which constitutes just under 13 per cent of the total population.7 Sixty per cent of the 36.4 million black Americans live in ten states: New York, California, Texas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, North Carolina, Maryland, Michigan and Louisiana. It is not surprising that the legacy of slavery, and the subsequent attempts to prevent blacks from participating in the political system, led to apathy and alienation. In the 1980s and 1990s black Americans increasingly played an important role politically and the number of black elected officials rose rapidly. In 1993 there were 7,984 compared with 6,056 after the 1984 elections, 4,963 in 1980 and only 1,479 in 1970.8 The biggest rises have been in the South where until the 1960s segregation of the races was openly practised. This change was symbolised by the election in November 1989 of Douglas Wilder, a descendant of slaves, to be Virginia’s Governor, the first elected black Governor in American history.

The 108th Congress, elected in 2002, included 37 black members in the House of Representatives or 8 per cent of the total, but Carol Moseley Braun, who in 1992 became the first black US Senator since 1978 as well as becoming the first black woman to serve in the upper chamber (see Table 1.3), lost her seat in 1998. The most dramatic increase has been among black mayors who now number over 300 compared with 86 in 1972. In recent times many major cities, including Washington, DC, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, Atlanta and Baltimore, have had black mayors. The election of New York’s first black mayor, David Dinkins, in 1989, after defeating three-term incumbent Ed Koch in the Democratic primary, was also seen as a landmark, while the election of black mayors in Seattle and New Haven was notable in that they are cities with relatively small black populations. Since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which led to federal supervision of elections in areas which had used discriminatory methods to deter them from registering to vote, millions of blacks have been added to the electoral rolls and this was further stimulated by the presidential primary campaigns in both 1984 and 1988 of the Reverend Jesse Jackson who inspired many blacks to take part in politics for the first time. In the 1996 presidential election there was both a notable increase in the turnout of black voters and a decline in overall participation.

Table 1.3 Black and Hispanic members in Congress

This increase in political power has been accompanied by the growth of a substantial black middle class which has been helped by anti-discrimination legislation and affirmative action programmes that have led to improved access to higher education and professional and managerial jobs. The contrast between the success of these black Americans, most of whom are among the 25 per cent of black families living in the suburbs, and the problems of an increasing ‘underclass’ based in decaying city centres and afflicted with drug addiction, violence, widespread illegitimacy and the threat of AIDS is indeed a stark one.

America’s fastest growing minority group is the Hispanic or Latino population (mainly Mexican-Americans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans). The 2000 census showed 35 million Hispanics living in the United States, a 58 per cent increase over the previous decade and more than 12 per cent of the total population, very similar to the proportion of black Americans. The Bureau of the Census reported that by July 2001 the Hispanic population had risen to 37 million and was greater than the number of African-Americans which stood at 36.1 million. By 2050 it is estimated that the Hispanic population will have grown to almost a quarter of the total population of the country as a result of continuing immigration and the relative youth and high birth rates of its peoples. Some demographers have predicted that if the rate of growth continues Hispanics could even become the majority population by the end of the twenty-first century; at present whites constitute 70 per cent of the total US population.

The Voting Rights Act has also been important for Hispanics because it bans literacy tests and requires certain states and localities to provide assistance in voting in languages other than English. In 1994 5,459 Hispanics held public office,9 while the 108th Congress had 23 Hispanic members or 5 per cent of the total. Leaders of the Hispanic communities saw increasing voter registration and participation among their people as their major political task in the next decade. Four out of ten Hispanics residing in the United States are not citizens and therefore not entitled to vote. Of those who are citizens only 57 per cent are registered to vote and therefore, although they make up 11 per cent of the voting age population, the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- 1. The Framework of American Politics

- 2. Making the Laws: The American Congress

- 3. Law Execution: The President and Administration

- 4. Law Adjudication: The Supreme Court and the Judiciary

- 5. Pressure Group Politics

- 6. Party Politics

- 7. Elections and Voting

- 8. Federalism, the States and Local Government

- Notes

- Appendix I: The Constitution of the United States

- Appendix II: Presidents and Vice-Presidents of the United States

- Appendix III: Glossary

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access American Political Process by Alan Grant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.