CHAPTER ONE

Nationalism and self-government in northern Africa

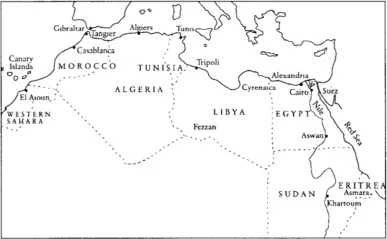

Northern Africa stretches from the Spanish fishing grounds off the Western Sahara to the Italian colonies of the Eritrean highlands above the Red Sea. At the end of the Middle Ages northern Af rica maintained close contact with Portugal, Castile, Aragon, Genoa and the Byzantine empire, while in the sixteenth century most of the region fell under the Turkish influence of the Ottoman empire. In the the nineteenth century northern Africa was parcelled out into eight European-ruled territories. Unlike much of tropical Africa, northern Africa attracted significant numbers of foreign immigrants. Most of these came from the opposite shore of the Mediterranean and settled in farming and trading communities not dissimilar to the communities created in the region 2,000 years earlier by European immigrants from the Greek city-states and the Roman empire. The modern settler colonies, how ever, only lasted for about 100 years. In the second half of the twentieth century most immigrants returned to the northern shores of the Mediterranean, sometimes followed by significant numbers of North Africans who became gastarbeiter in the prospering new economic community founded by Europe in 1957, just when the colonizers were beginning to leave Africa. The first of the north African territories to regain its independence of action after the imposition of European domination was Egypt.

During the First World War Britain had transformed its three decades of financial control over the kingdom of Egypt into a formal protectorate. This enabled it to assume full domination of the country while adjacent Arab territories, in the Turkish empire, were nominally linked to Germany. In 1922 Britain felt that its strategic hold on the Middle East was secure enough to end the protectorate over Egypt, although independence was on restricted terms. In particular, the interests of the million foreign residents in Egypt— mainly Greeks, Italians, Armenians and others who formed a tenth of the Egyptian population and a majority of its wealthier residents—remained under the protection of a British high commissioner. Nominally Egypt was ruled by the king and his prime minister, but the uncrowned high commissioner retained authority for foreign affairs, defence and the security of the Suez Canal. Decolonization, in Egypt as elsewhere, was only to be granted in carefully controlled stages.

The economic legacy of British control lay in the cotton fields. Britain had encouraged the growing of cotton to the exclusion of crops that were potentially more useful or valuable to the Egyptians, and had insisted that it be exported raw to the mills of Lancashire rather than processed locally for the benefit of the Egyptian industrial economy. It was a primary concern of Britain, and indeed of other colonial rulers of African territories, to try to ensure that the transfer of political power did not undermine the inexpensive supply of colonial-type raw materials and the profitable sale of finished products to former colonies. Thus, while Egyptian nationalists aspired to develop their own energy resources by damming the Nile and to spin their own cotton for their own textile industry, Britain endeavoured to restrict such bids for economic independence. The confrontation over economic decolonization, however, was postponed by the Second World War, during which British interests in Egypt were, as in the First World War, as much strategic as commercial.

After the Second World War three political traditions tried to win dominance in Egypt and restore the nationalist agenda of full political, military and economic independence. At first the liberals of the parliamentary monarchy that had governed after 1922 recovered their political role, but they were somewhat tarnished by their history of compromise with the foreign business interests that propped up a cosmopolitan (and allegedly decadent) royal court flaunting its wealth while the poor went hungry. A rival tradition, fostered by Muslim brotherhoods, wished to proclaim the supremacy of Egyptian cultural traditions and adopt a patriotic and puritanical agenda that excluded from public life all aliens and their Westernized Egyptian clients. The third political tradition grew up among a new class of young army officers. They had been recruited among “Arab” lower-middleclass Egyptian nationals rather than among upper-class white Egyptians, but they had been educated in English and trained in Western military traditions. Their political agenda involved challenging both the court with its culture of inequality and privilege, and also the Muslim brotherhoods with their backward-looking attachment to tradition. For Egypt to make real progress towards nationwide prosperity the officers also aspired to reduce the quasi-colonial domination of Britain and diversify foreign economic partnerships.

The military gained power in 1952 through a coup d’état that gradually became a revolution. The soldiers were acclaimed by crowds who, shortly before, had rioted in front of the colonial villas, cabarets and banks of Cairo. Their vision of decolonization was linked to a programme of industrialization that would turn peasants into industrial workers and give Egypt the standard of living hitherto enjoyed by Lancashire. Without coal or oil, however, they needed hydroelectricity on a large scale and this required a grandiose plan for the damming of the Nile. The Egyptian business class, frightened by the growing radicalism of the nationalist agenda and the prospect of crown properties becoming nationalized, had been moving their assets out of the country; domestic capital could not be raised on a scale sufficient to implement the grand vision of economic transformation. The revolutionary government therefore looked abroad for investment capital and initially found it in the United States. Very rapidly, however, the Western offer to invest in Egypt’s revolutionary agenda was withdrawn when the United States realized that the independent-minded Egyptian leaders were also conducting business with America’s Cold War rivals in the Soviet empire. In 1956 the politics of energy, industry and the Nile dam became linked to the politics of foreign influence over the Suez Canal.

Egypt’s Suez Canal, built by France and guarded by Britain, was internationally important for two reasons. First, it provided the shortest strategic route between Europe and Asia for military vessels patrolling the colonial and ex-colonial spheres of influence surrounding the Indian Ocean. Secondly, it provided the cheapest means of shipping petroleum from the great Iranian and Saudi oil fields to the Mediterranean and North Atlantic ports. Foreign ownership, management and defence of the canal caused each generation of Egyptian nationalists to feel that their independence was only partial and that British troops defending the canal were a constant threat to their sovereignty. This unresolved antagonism was exacerbated in 1956 when Britain joined America in refusing to finance the building of a high dam on the Nile. The soldier-politicians decided to solve two outstanding problems at once by nationalizing the canal and using revenue from the canal to pay the interest on loans to build the dam. Although the nationalization was properly conducted according to approved financial custom, the challenge to British and French supremacy in the area was unacceptable and they conspired to recover the canal by military means, and if possible to replace the radical nationalist government with a more pliant one.

The Anglo-French invasion of Egypt in October 1956 did not achieve its objectives. On the contrary, it weakened both of the leading colonial powers, strengthened the influence of the two super-powers in Africa, and made the Egyptian nationalists into heroes throughout much of the colonial world. Gamal Abd al-Nasser, the Egyptian president, became a name reviled in the Europe he had shamed, but idolized in Africa where colonial subjects began tuning into Egyptian radio broadcasts. They learnt about decolonization and the retreat of empire, about the aid programmes established by the Soviet Union, and about the way in which the United States had determined that Africa should be handed back to the Africans and had forced Britain and France to end their military invasion. A chastised Britain was compelled to ration petrol to its motorists until the Egyptians had cleared the war debris from the canal and reopened the shipping lanes to the oil refineries. The British Government of Anthony Eden disintegrated and in 1957 power passed to Harold Macmillan, who soon became the great decolonizer of the British Empire in Africa.

The second challenge to British colonial rule in northern Africa came from the Sudan, a colony that was theoretically the joint responsibility of Britain and Egypt but which had in effect been ruled by Britain since Egypt had gained self-government in 1922. In 1948 internal colonial democracy was granted to the Sudan and elected politicians debated whether the country should seek unification with Egypt (whose first republican president had had a Sudanese mother) or whether it should claim full independence. The dominant northern politicians opted for independence on the model chosen by Burma; in 1956 Sudan became a republic and did not join the financial and diplomatic club of former imperial dominions that were becoming a British-led commonwealth of nations. But rapid and total decolonization did not solve the fundamental problem of Sudan’s deep division between north and south. The south was racially black in contrast to the north, where a thousand years of Arab immigration had created a light-skinned population, and educated southerners spoke English not Arabic and worshipped in Christian churches rather than Muslim mosques. The two cultural traditions broke into two political traditions that soon came into armed confrontation with each other and the Sudan spasmodically suffered from long periods of civil war. The cultural heritage of empire permeated both sides, bringing to the forefront of politics British-trained officers in the north and Christian converts in the south.

The Second World War had brought a temporary reversal to the long-term trend of British disengagement from northeastern Africa. Both the intensity and the extent of British influence was increased. Indeed, one of the great turning points of the war took place on Egyptian soil when the German Afrika Korps, commanded by Rommel, tried to capture Egypt and open a route to the Middle Eastern oil fields by which to fuel German industry and the German war machine. The drive was halted at El Alamein, outside Alexandria, by a British army commanded by Montgomery. This army brought new prosperity to some Egyptians but also stimulated anti-British sentiments among nationalists and intensified the anti-Western attitudes of Muslims. The latter saw their country being corrupted by soldiers needing to recuperate from desert warfare by patronizing bars and nightclubs staffed by unveiled Egyptian women. In the short term the war not only greatly increased the British presence but also carried British influence beyond its historic sphere in Egypt and Sudan. British soldiers and administrators moved into neighbouring Italian spheres of influence in northeastern Africa and began a process of decolonization in Eritrea on the eastern flank and Libya in the western desert.

Eritrea had become an Italian colony during the “scramble for Africa” and tens of thousands of Italians had settled in the cool highlands above the Red Sea salt deserts. In 1941 the colony was captured by Britain, which imposed a temporary military government until a decision about the colony’s future could be settled internationally. Eritreans were politically divided between Christians and Muslims and between those who saw their future as linked to the neighbouring empire of Ethiopia and those who sought independent statehood. In 1950 the United Nations decided that Eritrea should be linked to Ethiopia and a slow process of integration began. At first Eritrea retained democratic institutions and political parties of the type Britain encouraged in its self-governing colonies, but these were gradually wound down as Ethiopian laws replaced Eritrean ones and in 1962 Eritrea was formally absorbed into Ethiopia. Some Eritreans felt betrayed by Britain, which had merely liberated them from Italian rule in order to hand them over to Ethiopian rule. Some of Eritrea’s Italian settlers remained during the transition and even prospered under Ethiopian rule. But some Eritrean Christians and many Eritrean Muslims felt that their birthright had been denied them. Gradually, with an eye on decolonizing developments among their southern neighbours in eastern Africa, they began to seek a second independence (see Chapter 3).

The second Italian territory to be decolonized in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War was Libya. After the retreat of the German army, temporary British military rulers were the dominant force controlling both Italian-speaking settlers and Arabic-speaking Libyans. The British favoured the creation of a conservative monarchy that would unite the three regions of Libya and govern them as a single country without any radical upheavals. Their choice of king was Muhammad Idris, the head of the Sanusi religious order, who had returned from exile in Egypt to become the emir of the eastern province of Cyrenaica. In Tripoli, where Italian colonial influence and authority remained strongest, and where nationalist aspirations focused on the creation of a modern industrializing state, the urban population vigorously opposed the British-sponsored agenda for decolonization. By 1951, however, the nationalists acknowledged the United Nations decision that Libya must become independent, and accepted that the best compromise was a federal system in which the province of Tripoli would have some autonomous powers under the overarching government of King Idris. In the nomadic and pastoral south, the province of Fezzan also retained some federal devolution of power. It was from the south that a new Libyan radicalism emerged, which challenged both the religious conservatism of Cyrenaica and the entrepreneurial nationalism of Tripoli. The movement grew up among soldiers who wished to cleanse Libya of its legacy of colonial corruption and adopt a pure form of patriotic and puritanical socialism. Its leader was a visionary colonel, Muammar al-Gaddafi, who aspired to give Libya the most independent government in all Africa. Ironically, he was helped in so doing by the discovery of oil that made Libya the richest country in the African continent.

While Britain was predominantly responsible for taking the initiative in the controlled decolonization of northeastern Africa, France was the main foreign power in northwestern Africa, the region known in Arabic as the Maghreb, “the west”. French influence in the Maghreb had grown up in a series of initiatives beginning with the conquest of the capital city Algiers in 1830. It continued with the settlement of European wheat farmers and wine-growers in the Algerian coastlands, and with the conquest of the Algerian hinterland of mountains and deserts. In the 1880s French influence spread eastward with the creation of French Tunisia. Domination of the Maghreb culminated in 1912 with the establishment in the west of a French protectorate over the ancient sultanate of Morocco, a kingdom that, unlike the other territories obtained by France, had proudly maintained its independence since the Middle Ages and never been conquered by the Ottoman empire. The northern and southern provinces of Morocco were partitioned off and given to Spain, which made claims dating back to the age of Columbus.

In 1940, less than 3 0 years after the annexation of Morocco, France itself was invaded and partitioned. French north Africa came under the influence of the quasi-autonomous regime of Marshal Pétain at Vichy and provided some logistic support to the German and Italian campaigns in Africa. In 1942 British and American forces opposed to Vichy, and nominally sympathetic to the rival French government-in-exile of General Charles de Gaulle, invaded the Maghreb via Morocco and Tunisia and established themselves in Algiers where Harold Macmillan became the British minister resident in north Africa. The Second World War, fought to proclaim the rights of nations to choose their own destinies, not unnaturally led north Africans to believe that they too would benefit from the principles of democracy and self-determination. Initially they were disillusioned. Algerians, who celebrated the end of the European war in May 1945, imagined that independence would now be theirs, but their demands turned into a riotous threat to colonial order; settlers were killed and many demonstrators were shot by white vigilantes, arrested by armed security forces or executed by the colonial law courts, Decolonization in northwestern Africa was delayed by ten years.

The decolonization of Algeria caused a prolonged and destructive confrontation between Europe and Africa, the “savage war of peace”, as Macmillan’s biographer, Alastair Horne, called it. The prelude to this colonial war, and to the granting of independence, however, took place in the neighbouring territories of Morocco and Tunisia. From the relative safety of Tangier, a Moroccan free port under international control, the sultan of Morocco began subversively to proclaim his country’s right to escape from French tutelage and join the independent Arab nations of the Islamic world. At the same time, the Moroccan working class organized strikes demanding better conditions in a country dominated by the economic interests of European settlers and businesses. The conflict increased in intensity, the French deposed the sultan, townsmen boycotted French goods, countrymen took up arms in irregular guerrilla forces, and politicians demanded immediate independence. In 1956 France, having lost one colonial war in Indochina and embarked on another in Algeria, gave way and the sultan returned to become the independent King Mohamed V of Morocco.

On Algeria’s eastern flank Tunisia underwent a similar confrontation with France, although the traditional ruler, the Bey of Tunis, did not play a comparable role in ending the protectorate to that achieved by the sultan of Morocco. The nationalist leadership was rooted in an old and well-established urban bourgeoisie whose traditions dated back to the great days of Carthage before the Roman conquest. The Arab politicians had to tread a wary path, listening to the demands of a proletariat whose post-war standard of living was declining, while at the same time negotiating with France over their own middle-class interests. French politicians, on their side, were anxious to avoid the expense of repressing yet another colonial rebellion, but could not ignore the stridency of French settlers in Tunisia anxious to preserve their social and economic privileges. Settler opposition to even gradual political reform blocked the establishment of a Tunisian parliament and led to the arrest of even the most pragmatic of Tunisia’s nationalists, Habib Bourguiba. As in Morocco, however, France soon decided to reverse its policy, released the martyred but essentially moderate statesman, conceded internal self-government, and finally granted independence in 1956. Three weeks after the decolonization of Morocco, Bourguiba became president of Tunisia.

The relatively rapid decolonization of all the northern African protectorates, from Morocco to Eritrea, in the ten years following the Second World War, naturally led Algerians to presume that they too could expect to recover responsibility for their own affairs. Algeria, however, was constitutionally very different from any other country in Africa and was administered as though it were three departments of metropolitan France. Formally, relations between France and Algeria resembled relations between Great Britain and Northern Ireland more than those between Europe and Africa. Economically, the situation was very different from other colonial relationships. The scale of French trade and investment in Algeria matched in scale the economic commitments of France in all the other territories of its empire put together, Thus it was that French financiers, and their political associates in Paris, were more reluctant to transfer political power in Algeria than they were in the protectorates or the tropical colonies. Furthermore, the scale of French emigration to Algeria far exceeded the scale of emigration to other French colonies such as Madagascar or Senegal. Indeed, there were almost as many French settlers in Algeria as there were British settlers in South Africa, and the Algerian settlers were almost as strongly attached to their adopted homeland as were the Dutch-speaking Afrikaners in South Africa. The settlers became known as the pieds-noirs, the black feet; many were small farmers with their feet rooted in the soil of the black continent. Their lack of alternatives and their fierce peasant determination, like that of the Boer farmers of South Africa, to hold on to what they had won, made it very difficult for the settlers to adapt to changing circumstances. They could not envisage access to new opportunities in the way that the commercial and professional middle classes of many colonies were able to do when seeking profit from changing political circumstances. Thus it was that Algerian nationalists faced a much more difficult task in seeking independence than did Tunisians or Egyptians.

The first formal demand that Algeria should be given independence came not from an educated nationalist elite seeking a political voice inside Algeria, nor even from Algerian Muslims who wanted the restoration of their personal rights and religious dignities, but from the leaders of the 100,000 Algerians who worked in France during the years following the First World War. Their political organizer, Messali Hadj, was a former labourer, army conscript and market barrow-boy who studied classical Arabic and married a French communist. His political agenda...