This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores body images in visual culture, from revolutionary France to contemporary New York. It engages with artists' use of different kinds of body images in painting, sculpture, photography and film, and shows the centrality of the body in the work of artists from da Vinci to Manet.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Bodyscape by Nicholas Mirzoeff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BODYSCAPES

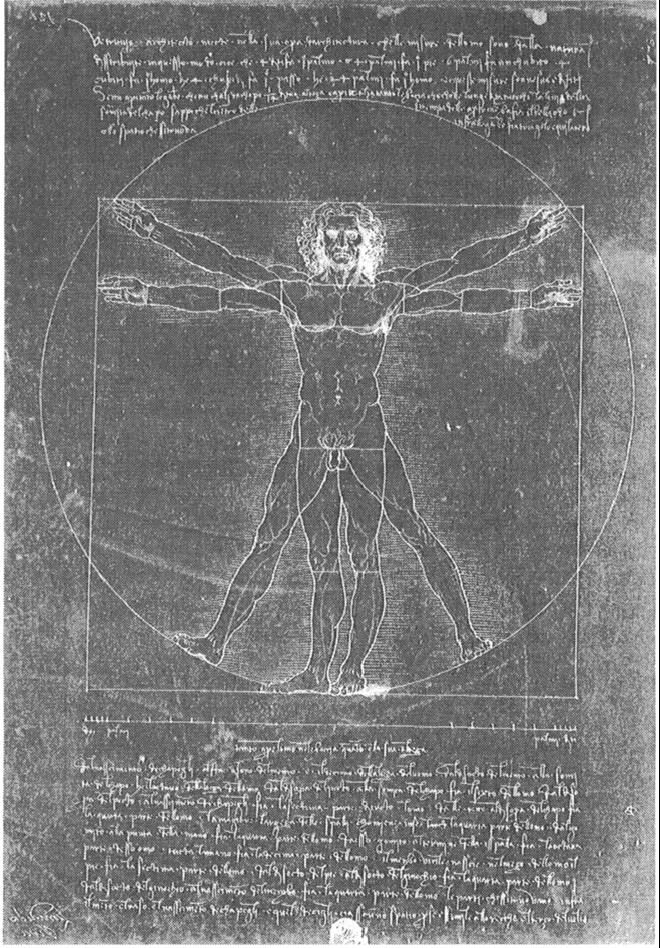

The discipline of art history rests on certain key assumptions, which are indispensable to its normal operations. One of these, presented to every student who ever takes an art history survey course, is the specific concern of this book, namely the thesis of the perfectly expressive human form, It is exemplified by the drawing of Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 3), which has become one of the most reproduced and well-known images in Western art. The male figure is represented twice, once standing, the other with arms and legs extended. In this way, the proportions of this ideal body represent the dimensions of two perfect forms, the circle and the square. Vitruvian Man has become the expression of a belief in the perfect form of the human body that art enacts. In this image, the body and its image are not separate but uniquely together. The body functions, like the circle and the square, as a signifier that exactly expresses its signified. There is no excess, no unexplained dimension or activity, an idea which has recently gained a new currency in certain conservative circles within art history.

However, I shall work from the assumption that the tension between the imperfection of the body in itself and the idealized body in representation is a condition of its representation. The sense of dis-ease which results from such awareness has motivated both art practice and criticism of representations of the body; or bodyscapes, as I shall call them. In his late work, Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud argued that all the sources of unhappiness originate outside the sphere of the ego, which believes itself to be secure and distinct from the ‘outside’. The first point of that outside, and the first cause of unhappiness, is the body: ‘We shall never completely master nature; and our bodily organism, itself a part of that nature, will always remain a transient structure with a limited capacity for adaptation and achievement’ (Freud 1961:33). The first source of bodily dis-ease is its inevitable insufficiency. In her definition of the body, Elizabeth Grosz expands upon Freud’s notion:

By body I understand a concrete, material, animate organization of flesh, organs, nerves, muscles, and skeletal structure which are given a unity, cohesiveness, and organization only through their physical and social inscription as the surface and raw materials of an integrated and cohesive totality. The body is, so to speak, organically/biologically/naturally ‘incomplete’; it is indeterminate, amorphous, a series of uncoordinated potentialities which require social triggering, ordering, and long term ‘administration.’

(Grosz 1992:243)

Figure 3 Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice/ Bridgeman Art Library.

Representations of the body are one means of seeking to complete this inevitably disjunctured entity. The coherence of the represented body is, however, constantly undermined by the very incompleteness these images seek to overcome. The body is the object of whose materiality we are most certain, but the undefinable potential of that inevitably incomplete materiality remains a constant source of unease. In this sense, the body is conceived less as an object than as an area, which gives us a strong sense both of location and dislocation, as the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy observes:

Bodies are not ‘full’, of filled space (space is always full): they are open space, that is to say in one sense, space that is properly spacious rather than spatial, or that which one could perhaps call place. Bodies are places of existence, and there is no existence without place, without there, without a ‘here’, a ‘here it is’ [voici] for the this [ceci]. The body-space is neither full, nor empty, there is no outside nor inside, any more than there are no parts, no totality, no functions, no finality.

(Nancy 1992:16)

The impulse to represent the body in visual culture is located within these contradictions. The dimensions, sources and history of this compulsion to represent the body form the ground for this book.

BODY FRAGMENTS VERSUS UNIVERSAL FORMS

Leonardo himself did not believe that one body alone could signify perfectly without outside assistance, and knew that his natural figure of Man needed to be completed and supplemented with artificial techniques of the body. For example, in describing how to represent gesture, he advised artists to imitate the sign language of the deaf:

The forms of men must have attitudes appropriate to the activities that they engage in, so that when you see them you will understand what they think or say.

This can be done by copying the motions of the dumb, who speak with movements of their hands and eyes and eyebrows and their whole person, in their desire to express that which is in their minds. Do not laugh at me because I propose a teacher without speech to you, who is to teach you an art which he does not know himself, for he will teach you better through facts than will all the other masters through words.1 (Leonardo 1956:105)

Leonardo knew that the visual arts of his day were inevitably silent, and that the forms of the body he depicted in his work did not necessarily create an intelligible story on their own. He thus used the technique of sign language in order to overcome the insufficiency of his representations of the body. It requires, in other words, an assembly of various fragments of bodily attributes to create one functioning bodyscape—even Vitruvian Man has a double. He might even be deaf.

In the last ten years, however, there has been a return in art history and criticism towards a Classical ideal of the body. Undoubtedly, part of the motivation of this move has been a desire to escape the seeming cynicism of the contemporary moment, a belief that everything has been done before. Rather than attend to the irony inherent in the postmodern practice of citation, conservative critics have taken this parodic and humorous strategy as the literal expression of a culture without ideas. In the words of British critic Peter Fuller, founding editor of the influential journal Modern Painters, there is ‘a prevailing tendency towards general anaesthesia’. Needless to say, Fuller and his fellow travellers are exempt from this charge, and are alone able to perceive the damage being done by the philistines. Modern Painters under Fuller was well designed and presented, with an acute sense for publicity, and combined a certain ‘common sense’ hostility to contemporary art with a voguish British triumphalism. Unlike many conservative critiques of contemporary art, however, Fuller was not simply against art, but stood for a clear and increasingly influential position. Until his early death in 1992, Fuller embodied the art historical direction of what Stuart Hall has called ‘The Great Moving Right Show’, incarnated by the Thatcher government. In the late 1970s Fuller challenged John Berger for the role of leading Marxist art critic, only at once to undergo a crisis of committment and to reemerge, like his model John Ruskin, as a Tory of the old school. He now believed that conservatism meant an opposition to all things modern, whether political or artistic, and a defence of tradition. Fuller was as opposed to Margaret Thatcher, whom he saw as a radical, as he was to his one-time colleagues on the Left. He uniquely compared the Marxist John Berger and Tory cabinet minister Norman Tebbit as similarly anaesthetic critics. Fuller equated Tebbit’s comparison of tabloid newspaper pin-ups with old master painting and Berger’s discussion of the nude in Ways of Seeing (1972).2

Fuller pursued a very English and very corporeal line in his conversion to what he called moral criticism. In an earlier flirtation with pyschoanalysis, Fuller rediscovered the human figure as a means of reviving the arts. He approvingly quoted the nineteenth-century art historian Walter Copland Perry on the Venus de Milo: ‘The figure is ideal in the highest sense of the word: it is a form which transcends all our experience, which has no prototype or equal in the actual world, and beyond which no effort of the imagination can rise’ (Fuller 1988a:15).Although this Platonic reading of the human figure had long been a staple of aesthetics, it struck Fuller as having remarkable potential: ‘Since men and women at all times and in all places…possess roughly the same physical and sensory potentialities, it may be possible to identify a necessary (though not a sufficient) component common to all ‘good’ sculpture which is not subject to significant historical determination or cultural variation’ (Fuller 1988a:20). This idealist position overlooks the fact that it is precisely through the differences between our roughly similar constitutions from which culture gains its meaning. In the modern period in particular, those differences have been more observed and more instrumental than ever before and cannot be wished away.

For in the nineteenth century, biologists such as Lamarck and later Darwin reversed traditional notions of divine creation in favour of an evolutionary schema of the development of human, animal and plant species. Rather than being considered an unchanging copy of divine perfection, the human body now had to be considered as one evolving species among many. As long as human superiority was considered divinely ordained, there was no need to insist upon the perfection of human corporality, but now such idealism had to refute or evade evolutionism. Initially, the destabilizing effects of evolutionism were offset by the older thesis of polygenism, that is, the notion that the human species was not one, but composed of several distinct and incommensurable races. Darwin’s 1859 treatise, The Origin of Species, insisted instead that evolution had taken place within one unitary human race over a span of time that far exceeded the Biblical chronology. The inference was both that Linnaeus’ eighteenth-century division of humanity into European, African, Asian and American races was incorrect and that the human body had not ceased to change, nor would it in the future. Statistical reseach confirmed that the individual body is not a constant but changes rapidly in response to social conditions. The average height of French military conscripts was 1.65m in 1880, 1.68 by 1940, 1.70 by 1960 and 1.72 by 1974 (Dagognet 1992:169) The modern body is not universal or divine but regularly changes. This average conceals a much wider range of difference between social classes. Indeed, Social Darwinists such as Herbert Spencer used such ideas to restore traditional notions of essential differences between races and classes, whose origin was not now simply biological, but the biological reflected through the social. In 1886, Lord Brabazon informed his readers of another world beyond that of the middle class:

Let the reader walk through the wretched streets…of the Eastern or Southern districts of London…. [S]hould he be of average height, he will find himself a head taller than those around him; he will see on all sides pale faces, stunted figures, debilitated forms and narrow chests. Surely this ought not to be.

(Steadman Jones 1971:308)

Brabazon’s proposed solution to the problem was biological imperialism via the relocation of the diseased masses in the colonies. His guiding principle was that the body not only changes but can be changed. Whereas Darwin had left the engine of evolution to nature, Spencer and the other Social Darwinists believed that they could direct evolution to their own desired ends. The consequences of these beliefs were both dramatic and tragic, leading to eugenics and extermination camps on the one hand; and the genuine achievement of modern medicine in preventing and curing disease on the other.

Fuller’s aesthetics depended upon the latest variant of such cross-fertilization between biology and social policy, the sociobiology espoused by E.O.Wilson. Sociobiology argues that social inequalities, such as the differences between men and women in modern societies, are the consequence of irrefutable biological differences and are thus natural. In this view, evolution takes place only within strictly contained parameters, rather than affecting the entire species, returning sociobiologists to the theories of Linnaeus. Despite the widespread condemnation of these ideas as scientifically unsound, sociobiologists hold that human behaviour can only be understood as a response to inherited genetic dictates. In the words of Richard Dawkins, a biologist whose writings have achieved considerable popular success, ‘the genes are the immortals… individuals and groups are like clouds in the sky or dust-storms in the desert’ (Shilling 1993:48–53). Fuller adapted this position into an new aesthetic which held that modernity was not simply ugly but contrary to our biology. He quoted Wilson: ‘Is the mind predisposed to life on the savanna, such that beauty in some fashion can be said to lie in the genes of the beholder?’ Fuller’s answer was in the affirmative, leading him to assert that modern architecture was antipathetical to our ‘natural’ desire for the curved form: ‘the anger in the human soul rises up against the tower blocks’ (Fuller 1988b: 233). It is similarly clear that this biological sense of the aesthetic is felt more profoundly by some than others. Ironically enough, given its assertion of humanity’s African origins, a sociobiological aesthetic is the return of white supremacism in disguise.

Fuller’s position was symptomatic of a new direction among conservative groups in contemporary art and politics in both the United States and the United Kingdom. The ultra-Conservative political position Fuller occupied has now crystallized into a die-hard block on the right wing of the Conservative party in the British House of Commons, united by a hatred for foreigners in general and Europe in particular. In the United States, Senator Jesse Helms led an assault on the National Endowment for the Arts, which articulated a sense of rage in conservative circles that the human body was being ‘violated’ by artists. Under the Reagan/Bush administration sociobiology gained respectability in government. One Bush appointee, Frederick K.Goodwin, instigated a furore in February 1992, when he advised a meeting of the National Health Advisory Council that inner city violence could well be understood with reference to the behaviour of primates: ‘Now one could say that if some of the loss of social structure in this society, and particularly within the high impact inner city areas, has removed some of the civilizing evolutionary things that we have built up and that maybe it isn’t just the careless use of the word when people call certain areas of certain cities jungles, that maybe we have gone back to what might be mos natural, without all of the social controls that we have imposed upon ourselves re as a civilization over the thousands of years in our own evolution.’ Goodwin was evidently referring to those parts of American cities in which African-Americans or Latinos are in the majority, rather than the white suburbs. His argument blend a Freudian sense of civilization as a restriction on instinctual behaviour, with the eugenic belief that in the unnatural environment created by humanity, evolutio no longer functions ‘correctly’, that is to say, by promoting the survival of thn fittest. These arguments have not been heard in the political mainstream since th e active eugenic policy of sterilization and extermination of the ‘unfit’ in Hitler’s Third Reich.

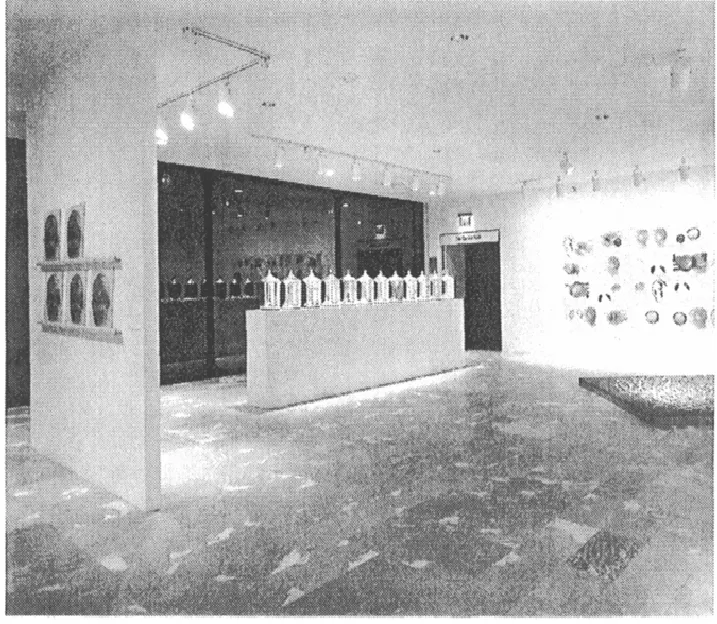

Figure 4 (opposite, top) Kiki Smith, installation view of the exhibition ‘Projects: Kiki Smith’, 10 November 1990–2 January 1991, MoMA, © 1995 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

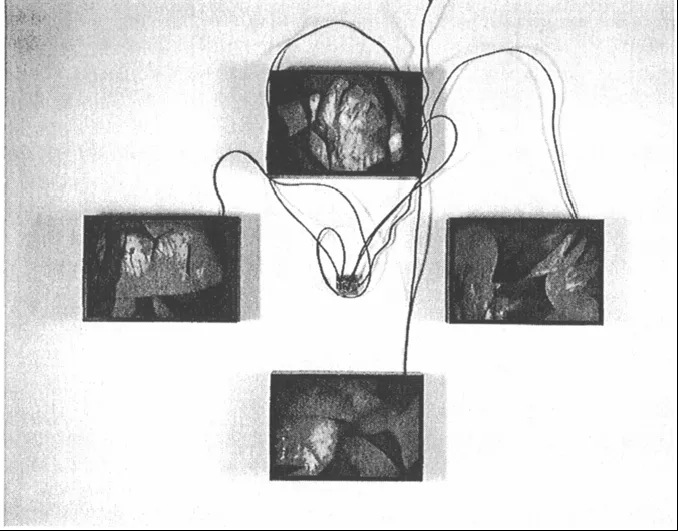

Figure 5 (opposi te, bottom) Kiki Smith with David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (1982–91), four photographic light boxes, photograph courtesy Pace Wildenstein, New York.

Those opposed to such ideas have often stressed that the postmodern body i not an ideal whole but an assemblage of fragments. In the contemporary world, such arguments run, the fragmentation of the body has become a fact of everyday body can be remoulded to any suitable shape. With the appropriate contact lenses, eye colour can be changed to match your clothes. Medical techniques t allow thousands of people to live with someone else’s vital organs replacin their own malfunctioning parts. In less radical fashion, it is common throughoug the West for people to control and change the shape of their bodies by dieting, exercise and body building.

A number of contemporary artists have made the fragmented body the subject of their work, most notably the American sculptor Kiki Smith. Her work has recently been branded ‘controversial’, after the National Endowment for the Arts withdrew funding from an exhibition in Boston, entitled Corporal Politics...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLEPAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: BODYSCAPES

- 2: THE BODY POLITIC

- 3: LIKE A VIRGIN?

- 4: PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE HEART OF DARKNESS

- 5: PAINTING AT THE HEART OF WHITENESS

- EPILOGUE FROM TERMINATOR TO WITNESS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY