This is a test

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Myth into Art is a comparative study of mythological narrative in Greek poetry and the visual arts. Thirty of the major myths are surveyed, focusing on Homer, lyric poetry and Attic tragedy. On the artistic side, the emphasis is on Athenian and South Italian vases. The book offers undergraduate students an introduction both to mythology and to the use of visual sources in the study of Greek myth.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Myth Into Art by H. A. Shapiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia antigua. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

THE WORLD OF GREEK MYTH

What we call mythology was, for the Greeks, the early history of their own people. They saw themselves in a direct line of descent from men of the Heroic Age, a period that modern archeological research would identify with the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1400–1200 B.C. Those heroes were, in turn, never more than two or three generations removed from that of the Olympian gods. Thus the gods, the heroes, and the “historical” Greeks of the Classical age formed, in their own view, one long continuum, albeit disturbed by periodic movements of peoples, invasions, colonization and the like. No wonder Hesiod, the Boeotian poet of the early seventh century, could complain that his own era, the Iron Age, was by far the worst in man’s history. For once men and gods had mingled freely with one another and were part of one extended family; but in Hesiod’s time, the gods seemed remote and uncaring, leaving man to eke out a miserable existence on his own.

In those hard times one of the Greeks’ few remaining pleasures was the memory of that earlier time, the many tales of heroes and gods that had been passed down over the long centuries conventionally known as the “Dark Age.” Only a generation or two before Hesiod, the poet we know as Homer had shaped some of these stories into a definitive form, as the Iliad and Odyssey. Even though these two epics cover only a fraction of the whole corpus of heroic saga, their most lasting impact was in creating a unified vision of the Heroic Age, of the nature of the gods and heroes, their relationship to one another, of fundamental issues of life and death.

At the divine level, Homer defined a pantheon presided over by Zeus, the “father of gods and men.” It is itself an extended family, with most of its members either Zeus’ siblings (sisters Demeter and Hera, also his wife; brothers Poseidon and Hades) or his various offspring (Athena, Apollo and Artemis, Ares, Hermes, Aphrodite). The intermarrying of gods and mortals is a practice well illustrated in Homer, through their offspring: Aeneas, son of Aphrodite by the Trojan noble Anchises; Sarpedon, the Lycian prince and son of Zeus; Achilles, son of the sea goddess Thetis by the Thessalian hero Peleus; and many others. The offspring all belong to the race of heroes, who, in the last analysis, despite their “godlike” qualities, are defined by their mortality. Because it is the fact of death that separates the heroes from gods, which in the end makes them so much more interesting, many of the myths turn on the motif of the death of a hero. Even when a story celebrates the prowess of a hero in his prime, this is usually demonstrated at the cost of another’s life.

Within the narrow focus of his two poems, Homer also managed to delineate one of the key aspects of Greek myth, its geographical dimension. The Greek army at Troy includes heroes from the whole length and breadth of the Greek mainland and the Aegean islands. The Trojan allies number several from Asia Minor with close ties to Greece through immigration and intermarriage. These are all summarized in the great Catalog of Ships in Book 2 of the Iliad. Greece is a small country in the modern world, but in antiquity the Greeks perceived an endless variety in the geography of their homeland and felt a powerful sense of identification with a native place. For them there were no “Greek” heroes, but Argive, Theban, Athenian, Corinthian, Cretan heroes, and so on, including the places in the Catalog of Ships that can no longer be located.

It would be left for other poets, who themselves originated in different parts of the Greek world, to gather the tales of heroes of their own city or region. Homer himself, whatever his origin (perhaps the island of Chios, as ancient tradition believed), is remarkably free of geographical attachments and seems to know the royal genealogies and myth history of every region of Greece. The Odyssey, of course, is about one hero from the island of Ithaca, but it is above all a poem of journey and discovery, and as such has a global perspective and a keen awareness of places outside the Greek world entirely (Egypt, Phoenicia). Every hero is localized in a particular place, yet each develops in the course of his career a network of contacts and relations, through common enterprises (the Trojan War, the voyage of the Argo) and travel abroad. It is in the interweaving of the many local traditions, the interconnections and interactions of one royal house with another, that the vast tapestry of Greek myth is created.

THE PLACE OF THE POET

This book is organized around the three principal genres of poetry in Archaic and Classical Greece. To some degree they form a chronological sequence, even if there were periods when more than one was practised. Modern opinion considers that epic poems in hexameter verse may have existed hundreds of years before Homer and circulated in oral form, performed by singers like Demodokos and Phemios in the Odyssey; but for us, epic poetry means primarily the two poems composed by Homer, probably in the second half of the eighth century. Ancient tradition preserves the names of several other epic poets, but none seems to have lived as early as Homer, and their poems, judged already in antiquity the work of inferior imitators of Homer, have not survived. This is a grievous loss, since, apart from the question of literary merit, these epics contained the whole corpus of heroic myths in their earliest organized telling: the Trojan War, both before and after the short excerpt of its tenth year recounted in the Iliad; the homecomings of the Greek heroes from Troy, other than Odysseus; the royal genealogies of Thebes and other major centers; the deeds and adventures of Herakles; and much more. Often visual sources are our best means of reconstructing the contents of these lost epics.

Hesiod is today also reckoned an epic poet, because he shared the dactylic hexameter of Homeric verse, although the subject and the structure of his poetry are quite unhomeric. There is, however, another reason why the ancients often referred to Hesiod and Homer in the same breath. Although written later, Hesiod’s Theogony can be read as “background” to Homer’s Iliad: that is, the Iliad describes a particular moment in the history of the cosmos, when Zeus and his family, from their home on Mt. Olympos, observe and control the destiny of mankind; from Hesiod we learn that this was not always so, but that Zeus is actually the youngest in a long line of divine rulers, his struggle to establish himself in power echoing that of many mortal kings. It was only with the combination of Homer and Hesiod that later Greeks could orient themselves with respect to the cosmos and their place in it.

The seventh and sixth centuries were the “Lyric Age of Greece,” as A.R. Burn dubbed it, because poets in all parts of the Greek world experimented with new forms and new metres, but usually setting their songs to the music of the lyre. All these poets were conscious of standing in the shadow of Homer, and some sought to avoid the comparison by writing short, intensely personal or occasional poetry far removed from the epic tradition. Others, however, recognized the creative possibilities of recasting epic material in various ways—for example, by detaching a single heroic episode from its epic context and elaborating it into a self-contained poem. Perhaps the most successful of these poets was Stesichoros, from Sicilian Himera, for whom many substantial works on a wide range of heroes are attested and one, on Herakles and Geryon, partially preserved on papyrus.

Among the last poets of the Lyric Age were Pindar and Bacchylides, both commissioned to write occasional verse for athletic victors and religious festivals. For Pindar, Homer and the Epic Cycle were far enough in the past that he could distance himself and even question their authority when the received version conflicted with his own vision of gods and heroes. Thus began a dialog between the Classical Greeks and their own heroic past that kept the myths alive and insured their continuing relevance in everyday life.

From the second quarter of the fifth century, that dialog was carried on primarily through the medium of tragic drama. In Athens itself this meant productions in the Theatre of Dionysos that extended the performance of poetry from small private occasions or religious sanctuaries with a limited audience to civic events accessible to all the citizenry; not only that, but the visual dimension of actors in performance must have given the old tales an immediacy that no Archaic poet/singer could match.

The three tragedians whose work (or a fraction of it) survives, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, each handled the conventions of drama in different ways. However, each in his own way used heroic myth as a vehicle for reflecting on the most pressing issues of his day: political, social, religious. Nor did they ever shy away from treating a subject that had already been dramatized by another playwright, for they recognized that each myth was open to multiple interpretations. Although we do not have the epics preserved from which they drew their material, we can infer that they seldom regarded these as fixed or sacrosanct; rather, the process of mythmaking was as alive and vigorous in the fifth century as in Homer’s own time.

THE PLACE OF THE ARTIST

The early development of the figural arts in Greece followed a trajectory parallel to that of heroic saga. In the Late Bronze Age, as the tales of heroes were first being shaped, painters of large frescoes and clay vases were thriving in artistic centers from Mainland Greece to Crete and the Cyclades, even on Cyprus. Many of their ambitious compositions look like illustrations of pre-Homeric epic and have been interpreted as such in recent years (Fig. 1). But with the collapse of Mycenaean civilization in the twelfth century B.C., this art-form disappeared, and even on decorated pottery no human figure would appear for several hundred years. The rediscovery of a figural style, on monumental funeral vases in the middle of the eighth century, corresponds exactly with the period when Homer would have been starting to gather the old stories into the ‘rediscovered’ medium of epic verse.

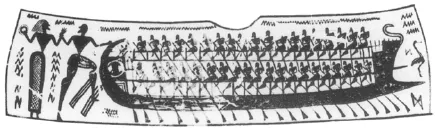

The question whether any of the so-called Late Geometric vase-painters, working in the second half of the eighth century, set out to represent specific heroic myths is a hotly debated one. There can be no question that many of their compositions are ‘narrative,’ in that they tell a story; however, the means at the painter’s disposal did not allow him to be as specific as the modern iconographer would like. Probably these scenes presented no problems of interpretation for the contemporary viewer. So, for example, the scene on a Late Geometric bowl (Fig. 2), of a man and woman embarking on a big oared ship, looks unquestionably like a heroic subject and not one drawn from everyday life. However, whether it represents Paris taking Helen on board to set sail for Troy, or Theseus leading Ariadne away from Crete, or yet another mythological couple, is, at least to our eyes, left open.

The question, then, is not when Greek artists first depicted heroic stories, but how they developed the narrative technique of making these stories immediately recognizable and increasingly complex, within the confines of the pot surface (since large-scale wall-painting seems not to have been re-invented until well into the sixth century). Here the seventh century, in spite of the impoverished state of our evidence, appears to have made all the most important advances. The first, perhaps, was simply the choice of subjects that, thanks to one or two basic narrative or iconographic elements, could be rendered with utter specificity. Thus, the simple combination of a human giant and a man or men driving a stake into his eye (see Figs. 30–32) could only be the blinding of Polyphemos. A second major advance of the Orientalizing style of the seventh century over the Geometric was the creation of a language of gesture and facial expression that greatly enriches the narrative. The figure of Klytaimestra as she witnesses the murder of her paramour Aegisthus (see Fig. 95) speaks volumes to those who know the story. Third, the seventh-century artist, capitalizing on the rapid spread of the alphabet throughout the Greek world, recognized its practical application in labeling his figures to make them readily identifiable. Where the subject is perfectly clear even without inscriptions, as in the suicide of Ajax (see Fig. 106), we can only think that the painter added them either to show off his own literacy or to appeal to a certain kind of clientele.

Figure 1 Shipwreck and landing party. Fresco fragment from Akrotiri, Thera. Athens, National Museum. Ca. 1450. After S.A.Immerwahr, Aegean Painting in the Bronze Age (University Park/London, 1989) pl. 27.

Figure 2 The abduction of Helen by Paris (?). Late Geometric bowl from Thebes. London, British Museum 1899.2–19.1. Ca. 750–700. After K.Schefold, Frühgriechische Sagenbilder (Munich, 1964) pl. 5c.

By the sixth century, we may assume that a great deal of epic poetry, by Homer and others, was circulating in oral form and, increasingly, in written form as well. We have evidence, for example, that ‘authentic’ texts of Homer were brought to or edited in Athens in the time of the Peisistratid tyrants (560–510). There were, in addition, the itinerant poets, like Stesichoros, performing their work at public events in the major religious and urban centers. Artists therefore had easy access to a wide range of material, and this is reflected in a veritable explosion of mythological representations from the early years of the sixth century. Although Corinthian vase-painters had rivaled Athenian in both quality and narrative sophistication (cf. Fig. 106), various market factors drove Corinthian wares into decline by the mid-sixth century, leaving Attic black-figure as our primary corpus of mythological scenes for the High Archaic period. These were also the years of the development of architectural sculpture as a medium of complex narrative. The continuous Ionic friezes of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, for example, are at times strikingly reminiscent of the Homeric vision of the Olympian gods.

The invention of the red-figure technique in Athens ca. 530–525 did not mark a sharp break in subject-matter, especially since black-figure continued in intensive production for another two generations. It is, nevertheless, astonishing how close a correlation exists in many cases between subject-matter and technique; that is, there are scenes that never made the transition to early red-figure (e.g. Herakles and Nessos, see Figs. 110–113) or were first introduced by the early generations of red-figure painters (e.g. Sarpedon, see Figs. 12 and 13).

There is barely a single mythological subject that can be said to enjoy continuous popularity in Attic vase-painting from early black-figure to late red-figure. The painters’ repertoire was constantly in flux, partly in response to outside stimuli, such as new literary works (e.g. the Theseus cycle, see Figs. 76 and 77) or, later on, dramatic performances (cf. Fig. 102), but partly also reflecting the internal dynamics of an art-form. At a certain point, some subjects had simply run their course—for example, the many animal and monster combats of Herakles that lost their appeal by the end of the sixth century (e.g. Geryon, see Figs. 46–51). The imagery of Greek myth never constituted a religious dogma, in the way that Christian iconography did, and could thus be much freer in both its choice of subject and mode of representation. The average Greek did not need pictures of the gods and heroes, as medieval or Renaissance man needed images of Christ and the Virgin. The painted vases that are the main subject of this book were mainly used in a purely secular and domestic context, most of them at the symposium, or drinking-party. If the Greek chose to surround himself with these images, then it was more for esthetic than religious reasons.

The red-figure pottery industry, like the city of Athens as a whole, was dealt a tremendous blow by the long years of struggle and ultimate defeat in the Peloponnesian War. Politically, the city recovered remarkably fast, but the potters and painters did not, and in the first half of the fourth century their craft died a slow and (to our eyes) painful death; but as early as the 430s some Athenians had set up shop in the colonies of Southern Italy and planted the seeds of a thriving industry in red-figure vase production that would continue nearly to the end of the fourth century. Its major centers were in the areas of Taranto (Apulian), Metaponto (Lucanian), and Capua (Campanian). Although, after this first generation of immigrants, the great majority of South Italian painters probably never set foot in Greece, it is a testimony to the strength and endurance of Greek tradition, in colonies established in some cases over 300 years previously, that mythological representations now reach a new high point of originality and fidelity to literary sources. Often these scenes can be recognized as responses to productions of Attic tragedies that were, for these Greek cities in the west, one of the primary direct links with their cultural heritage.

In the Hellenistic Age—after Alexander the Great and beyond the ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: EPIC

- 3: LYRIC

- 4: DRAMA

- BIBLIOGRAPHY