1

INTRODUCTION

The Emperor Gaius, otherwise known by his nickname Caligula (‘little boot’), came to power at the age of 24 in March ad 37, only the second man to inherit the principate. By January ad 41 he had been assassinated. For someone whose reign was so short he has certainly achieved notoriety. The name Caligula is synonymous with vice, depravity and even insanity. He was the standard example of the archetypal tyrant to his literary contemporary Lucius Annaeus Seneca. And that is how posterity has remembered him. But is there really historical evidence to support such a tradition? This work intends a reappraisal of Gaius by not only investigating his policy at home and abroad in the four years of his reign but also by comparing and contrasting this with those of his immediate predecessors and successors. His reign is too short to be treated in isolation. Only by searching for consistency of government with regard to Roman policy at the time can his reign be fully evaluated. Did Gaius diverge from Augustan precedent? Did he innovate in his domestic government or foreign policy, and if so were such actions successful? Did his successors continue his work?

By studying Gaius in this wider context, and by concentrating on his government, taking a more rigorously political approach, light will be shed on the value and consequence of his reign.

It is essential to investigate Gaius' government, and his relations with the various strata of Roman society, in order to understand how his assassination came about after only four years. In other words, who was against Gaius and why?

The principate that Caligula inherited was by no means an old institution. Augustus had spent years perverting the old Republic into a new Empire with a hereditary succession, and it was his sheer reputation and power, his auctoritas, that allowed him to put into practice his new ideas. There were always opponents of such an empire, adherents to the old ‘republican’ means of government, but Augustus’ process of change was both slow and subtle, ending in Tiberius' accession. Tiberius had respected the old order of things, even if his manner did not always make this obvious; he had been a senator and so had friends in the senate on his accession. The ‘republicans’ could have seen hope in their new emperor – the first to inherit the position in Roman history. Tiberius' early government would certainly have appeased such men. However, Tiberius eventually withdrew to Capreae where he stayed from ad 26 until his death. This facilitated the start of a reign of terror headed by Lucius Aelius Sejanus. The interface between the senate and their emperor broke down with Tiberius' absence from Rome; a petrified senate merely rubber-stamped imperial ‘orders’ that originated from the island of Capreae. This in turn aided Sejanus in bringing court cases against his enemies. There were many victims, including Caligula's mother, Agrippina, and brothers, Nero and Drusus.

Eventually Tiberius acted against Sejanus’ rising power and had him executed, which led to a further bloodbath as the city of Rome was purged of his supporters by an emperor paranoid about his own safety. Convictions filled Tiberius' last years, and even some of his friends fell, like Cocceius Nerva. By his death in ad 37 Rome had seen their princeps become more autocratic with every year; this was not Tiberius' wish, but the outcome of the political system, exacerbated by his retirement to Capreae and the paranoia surrounding the maiestas (treason) trials. Much blood had been spilled, and Tiberius' reputation was poor; he was hated by the senatorial class both for the deaths of their peers and for turning their body into a collection of people who merely ratified imperial orders, and by the people for the lack of games and shows provided by his reign. Tiberius had even banished actors altogether. He had, however, managed to maintain the line of succession and Caligula (with the young Gemellus) was to be his heir. Tiberius' rule had been austere and he respected the policies of his predecessor; there was no major attempt at expanding the Roman Empire, and no real innovations in his internal government.

When Caligula came to power his accession was celebrated across the Roman world. The maiestas trials had been put to an end and Rome looked forward to a new start under this new young emperor; on the shoulders of this son of Germanicus rested the hope of many.

2

UPBRINGING AND ACCESSION

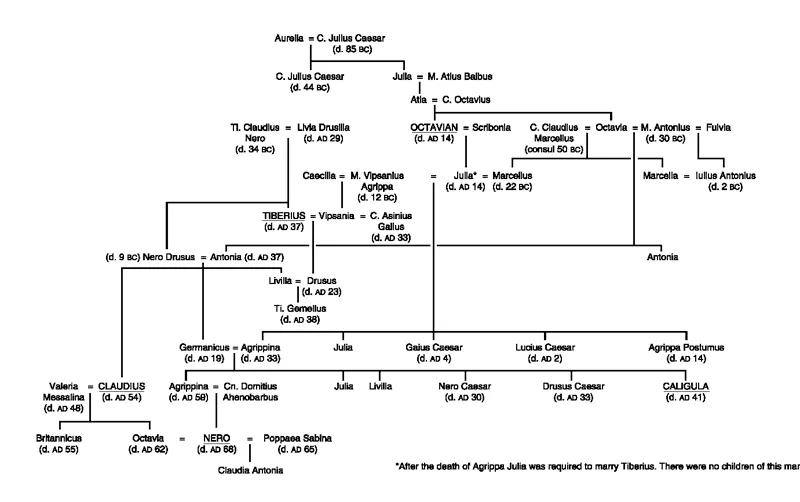

Caligula was born on 31 August ad 12 at Antium (Suet. Calig. 8) to a distinguished family. Through his mother Agrippina the Elder, daughter of Julia, he could trace a direct bloodline to Augustus himself and the powerful Julian family. His father's family were no less distinguished; Caligula was the great-grandson of Livia, the strong Claudian wife of Augustus. He was a true Julio-Claudian, born directly into the imperial family.

In ad 14 he accompanied his mother and father, the popular Germanicus, to the Rhine where they would remain until ad 17.

Germanicus had inherited that title from Drusus who had crushed the Germans in 12–9 BC and reached the Elbe, and Caligula would be entitled to use it himself. Germanicus, sent there by Augustus, had instantly to deal with the death of the latter and the mutiny that followed on the Rhine. The accounts show that Germanicus certainly had trouble in putting it down. The soldiers saw the death of Augustus as a perfect time to complain about various conditions of service, and this got out of hand. Although the sources claim they offered Germanicus their services in obtaining the principate for himself, the following events make this unlikely. Regardless, Germanicus was loyal to the new emperor Tiberius. The tradition has it that Germanicus could not quell the rebellion, and that it was the sight of his wife Agrippina the Elder, with her retinue and son Caligula, leaving the camp to seek solace with the tribe of the Treveri, that is supposed to have shamed the troops into subservience. Germanicus then let the men butcher the ringleaders of the mutiny and planned action in Germany to keep them busy. Whether Agrippina and Caligula were really involved in quietening the trouble is irrelevant; the anecdote shows the popularity of Caligula with the men. Moreover, Agrippina dressed Gaius in soldiers’ boots (which is how he got his nickname) and even had him called Caesar Caligula when in camp. She clearly contrived to endear Gaius to the men.

Figure 1 Stemma of the Julio-Claudian family

Germanicus then crossed the Rhine in a punitive expedition in order to raise the morale of his troops. After a modest success, where he was able to reach the scene of the Varus defeat and raise a funeral mound to the dead, the Roman legions were almost ambushed by Arminius and had to retreat, which caused severe panic back at camp. Another anecdote has Agrippina stopping the bridge over the Rhine being destroyed by those worried by fear of losing the camp; this move made sure Germanicus and his men were not cut off and massacred. Tacitus would then have us believe she gave out clothes and shouted words of encouragement to the returning troops. Again, the reliability of the story is not too important; the sources play Caligula's mother up as a strong woman, level headed and loyal to her husband. The fact that she was actually with her husband on the Rhine backs this up. In ad 16 Germanicus attacked again, this time with a fleet. On its return a storm wrecked a large part of it; this would be his last action in Germany before Tiberius called him back to Rome for a triumph.

In ad 17 Germanicus enjoyed his huge triumph, and sitting in the chariot with him as he passed the adoring public was Caligula, almost 5 years old. This must have been one of his earliest, and most poignant, memories. Germanicus’ exploits in Germany have not been seen as massive successes by modern scholars, but this did not affect his popularity with the Roman people and he secured for himself, and his children, a good reputation with the legions on the Rhine. However exaggerated the stories of Agrippina's role in the events are, she certainly contrived to make her son popular with the legions.

At 5 years old Gaius accompanied his parents on a new endeavour, this time to the East, where Germanicus was asked to settle the Armenian issue with Parthia. On the way they experienced huge displays of love from provincials as Caligula went on this grand tour. He even gave his first speech at Assos in ad 18 at 5 years old. Germanicus settled the dispute in Armenia by agreeing to the kingship of Zeno (Artaxias) and incorporated both Cappadocia and Commagene into the Empire. Germanicus died in ad 19 at 33 years of age amid rumours of foul play; this event set off a chain reaction that would see an obsessed Agrippina battle with Tiberius until it killed her. Germanicus’ death at the height of his popularity, and amongst rumours that it was at the hands of Piso, who had been sent East by Tiberius, was key in establishing the legend and ensuring that his popularity would live on after him. The mini-biography of Germanicus at the beginning of Suetonius’ Life of Caligula shows the extent of his popularity and renown.

In ad 20, at 7 years old, Caligula accompanied his mother and the ashes of his father back to Italy. Again, they were received everywhere by a huge crowd, this time in mourning.

Neither Tiberius nor Livia attended the funeral. Germanicus’ popularity across the Empire was huge; the rightful heir to the unpopular Tiberius had died and Agrippina was to do her utmost to make sure one of her sons would receive what she saw as Germanicus’ by right. She had witnessed how a headstrong Livia had schemed and managed against all odds to procure the principate for her son Tiberius, and she seemed obsessed with doing the same.

From Germanicus’ death onwards Rome seemed to become divided between the supporters of Agrippina, who used the popularity of Germanicus to her advantage, and the supporters of the praetorian prefect Sejanus. Tiberius and Agrippina openly quarrelled anyway, and this was exacerbated by Sejanus’ attempts to remove Agrippina's family from the succession. This developed into treason trials and the convictions of Agrippina's friends as she continued to provoke the princeps. In ad 24 the names of Gaius' older brothers were included in the annual oath of allegiance for Tiberius, possibly at Agrippina's instigation. This would be entirely in keeping with her actions to ensure the popularity of Gaius with the Rhine legions and led to severe reproach from Tiberius and more convictions for her supporters.

In ad 27 Tiberius left for Capreae and a 15-year-old Caligula moved in with his great-grandmother Livia. There he met the three Thracian princes (Rhoemetalces, Polemo and Cotys) and Herod Agrippa, all of whom would remain his friends and benefit from his later rule. Two years later Livia passed away and Caligula gave the funeral oration. He then moved in with Antonia. Livia has often been seen as a large influence on her son Tiberius, and with her out of the picture it may have been easier for both Sejanus and for Tiberius himself to get their way. In ad 30 Caligula's brother Nero committed suicide; he could not hold his tongue about his views on the emperor, a trait he undoubtedly picked up from his mother. In the year ad 31 Caligula was made a priest and at the ceremony there was a show of popularity towards him from the populace. He was then called to Capreae as a man of 18; in the same year Sejanus finally fell, but this did not stop the death of Agrippina and Drusus two years later in ad 33.

Caligula had experienced first hand the power struggle between his mother and Sejanus; he was aware of his popularity, but had not spoken out to aid his family. As a result he had saved his own life; he had luckily been too young to threaten Sejanus during the lifetime of the latter. Gaius would stay on Capreae with Tiberius until his accession in ad 37. On that island he would have been privy to the ravings of Tiberius, and seen the continuation of the maiestas trials. In fact, for most of his life these would have been a common occurrence. He saw the reign of Tiberius descend into more bloodshed and become more autocratic as the emperor retired to Capreae. One man was even accused of plotting against the young Gaius. Having no doubt been convinced by his mother of his birthright to rule, and being acutely aware of his own popularity, it must have come as no major surprise when Tiberius named him joint heir with Gemellus in ad 35.

Caligula had, however, no experience of governing; the extent of his education in this respect was being made quaestor for ad 33.

He had no formal training or major experience of the senate. He had been given no commands in the field, such as those given to Gaius and Lucius by Augustus. Instead he had been indoctrinated by an ambitious mother of the importance of his own family and their right to rule; he had been convinced of his own nobility; he had witnessed the autocracy of Tiberius' later years.

On 16 March ad 37 Tiberius died and Gaius acceded to the throne as a 24-year-old unknown; all he had was the popularity of his family and the reputation of Germanicus to introduce him to the Roman world. This family was very important to him, and would be honoured and used as a political tool throughout his reign.

The accession was a smooth one. Macro and his praetorian guard immediately swore allegiance to Gaius, and he sent word to the legions around the Empire to do the same. Two days later the senate followed suit; they were unlikely to go against the army, and they had no reason yet to dislike Gaius. Gaius accompanied the body of Tiberius from Misenum to Rome and did not arrive in the city until 28 March. The journey to the capital saw joyous crowds greeting the emperor and offering sacrifices to him; Caligula was used to such receptions by now. The people of Italy were ecstatic at the replacement of Tiberius.

Macro had the will of Tiberius declared null and void on the grounds of poor health; this way Gemellus had no formal position as joint heir, which Tiberius had bequeathed. It is possible Macro had friends in the senate who helped with this. He was certainly instrumental in the transition of power from Tiberius to Caligula.

Despite the will being declared null and void, Caligula still honoured Tiberius' legacies. The senate then granted Caligula all the powers and titles of Augustus in one block; Caligula only refused the title pater patriae, which sharply contrasted with Tiberius' reluctance to accept the principate altogether. It is believed that the Lex de Imperio Vespasiani, which probably conferred total imperial power, had its origins here. In short, Caligula was the first emperor to be given all the powers that Augustus and Tiberius had collected piecemeal over the years in one block from the outset; he had a free hand to do what he deemed best for the state. The popularity of Gaius' family allowed him to slip into the role of princeps with ease. The whole Roman world celebrated the accession of this completely unknown 24-year-old man, who had no background in politics or government and no experience of warfare. But what would this son of Germanicus do with his ‘absolute power’ (Suet. Calig. 14)?

3

DOMESTIC POLICY

To investigate the government of Gaius over Rome the measures he took, for example his taxes, must be looked at. It is unlikely that the sources would concoct edicts entirely, but we must be aware of the gross exaggerations that surround them; so when both Suetonius and Dio talk of Gaius' move to repeal the censorship laws with regard to certain individual writers we should take this as historical fact, if there is no evidence to the contrary.

Although reports in the ancient sources cannot easily be separated from subsequent interpretations, we must be wary of those interpretations given in the sources, and the evaluative comments found therein, and these must be treated with circumspection.

From Seneca and Philo, through Josephus and Suetonius, and ending with Dio, none of the literary sources had any reason to praise Gaius; they all, however, had an interest in his shortcomings (see Appendix 1).

So, to analyse his policy, its effectiveness, economic viability and popularity with the various strata of Roman society must be investigated fully. Whether it was in any way detrimental to that society, and whether Gaius drastically changed the policies of his predecessors, must be looked at. Where Gaius did bring in new laws, were such changes beneficial to Roman society, government and the economy, and were his innovations maintained by his successors?

FINANCE

The background to evaluating Gaius' government is a financial one; the sources claim Gaius was a bankrupt (Suet. Calig. 37; D.C. 59.2.6). Given the huge treasury Gaius supposedly inherited (either 2,300 or 3,300 million sesterces; D.C. 59.2.6) this is quite a charge, and would signify massive economic incompetence; we must investigate this first, ignoring the subjective claims of the sources that Gaius was a spendthrift and concentrating on the concrete charge that he was a bankrupt. Gaius may have been extravagant, but as long as he could afford to be, and the state did not suffer, there is nothing inherently wrong with this.

The difficulty of evaluating the fiscal policies of the Julio- Claudians, due to the division between the private wealth of the emperor and his income as head of state, has been pointed out. The large inheritance was partly illusory as not only Tiberius' but also Livia’s bequests had to be paid, and donatives had to be given to the soldiers and people.1 Moreover, such a large inheritance would have taken a vast amount of saving on the part of Tiberius, and so we should treat with scepticism the figure of 3,300 million sesterces as given in Dio and now look at the charge of bankruptcy.

The biggest piece of evidence against bankruptcy is that the early reign of Gaius' successor, Claudius, shows distinct affluence: he gave massive donatives, including 15,000 sesterces to each praetorian alone; he returned the fines Gaius had charged dishonest road contractors and even cancelled Gaius' taxes. Furthermore, he undertook expensive military campaigns, namely against Britain and Germany. He clearly had no financial problems in ad 41.

Gaius was still coining in precious metals in January of ad 41, and Claudius continued; this is not the sign of an empty treasury. Gaius supposedly brought in new taxes in late ad 40 to compensate, and these are depicted as ubiquitous and unpopular. Surely, though, these would not have been implemented in time to replenish an empty treasury, even coupled with Gaius' auctions in Gaul.

It is possible the lavish games Gaius put on and his extravagant rule, together with ‘popul...