![]()

PART I

WHO MIGRATES, AND HOW DOES IT AFFECT FAMILY OUTCOMES?

![]()

1

Ties That Bind: Immigration and Immigrant Families in the United States

Rubén G. Rumbaut

Michigan state University

Family unity has and continues to be the cornerstone of immigration policy for the United states. A point of debate ahout generous family unity policies is a concern that family immigrants take rather than contribute economically. Family-hased immigration is allege d to he an inefficient means of selecting workers that contrihutes to a decline in the skill levels of the workforce. Much of this argument misjudges the character of family-hased immigration. Family-connection immigrants are also workers. Immigrants are typically admitted under family reunification provisions who could also qualify in virtually all professional and technical occupations specified in immigration laws. Indirectly, family reunification also admits workers with skills. … More important, however is the economic and social role the family plays in immigrant adaptation. Families ease the considerable social and cultural dislocations caused by immigration and by serving as intermediaries to the host society, enable the newcomer to adapt. Family and household structures are also primary factors in promoting high economic achievement. They are crucial resources in the formation of immigrant businesses, which often revitalize urban neighborhoods and specialized economic sectors. These successful social and economic transitions lay the foundations that are needed if the children of immigrants are to be effective citizen-workers of the next generation.

—Meissner, Hormats, Walker, and Ogata, 1993, pp. 13–14.

There are two families in the world, as one of my grandmothers used to say, the Haves and the Have-nots.

—Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quijotc, (1605–1615: II, 20)

IMMIGRATION and “family values” are in the news these days—indeed, they are hot-button political issues in the presidential campaigns now under way. It is said that there is too much of the former and too little of the latter, but (with rare exceptions) no connection is made between the two. That disconnection reflects in part the relative lack of attention given to children and family in immigration studies; they are topics that belong to the realm of what David Riesman once called underprivileged reality. And yet, the family is perhaps the strategic research site (cf. Merton, 1987) for understanding the dynamics of immigration flows (legal and illegal) and of immigrant adaptation processes as well as long-term consequences for sending and especially for receiving countries, such as the United States. Kinship is also central to understanding U.S. immigration policies and their intended and unintended consequences. Marriage and close family ties, as Meissner et al. (1993) underscored, are the basis for longstanding selection criteria built into U.S. immigration law.

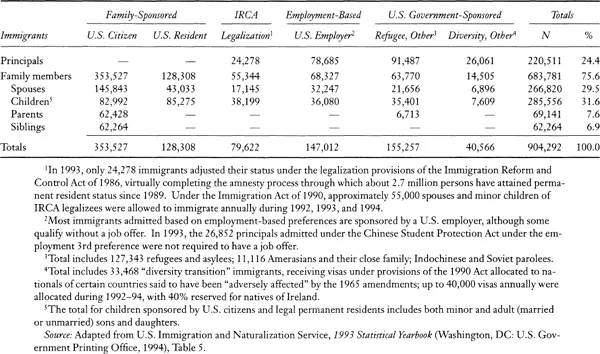

Consider the 904,292 immigrants legally admitted in fiscal 1993, the second year in which the provisions of the Immigration Act of 1990 were fully in effect. Table 1.1 summarizes the main types of categories and sponsorships for all immigrant admissions, including employment-based and diversity transition visas, refugees and asylees, and IRCA (Immigration Reform and Control Act) legalizations and dependents. At the risk of oversimplifying what is a highly complex process, gaining immigrant status generally requires a sponsor who may be a U.S. citizen or legal resident, a U.S. employer, or (especially in the case of refugees) the U.S. government. Of these, the principal route to legal immigration—in over 75% of all cases in 1993—involved a close family tie, a figure that actually understates the pervasiveness of family connections because many of the principals who entered as refugees or through nonfamily preferences already had relatives in the United States. As usual, the largest single mode of legal admission involved a marriage to a U.S. citizen. The 145, 843 spouses of U.S. citizens who were admitted as immigrants in 1993 was the highest total ever recorded, tripling the number of spouses admitted in 1970. Trend data over the past quarter century clearly show as well that immigration via marriage to a U.S. citizen has been growing much more rapidly than that of parents or children of U.S. citizens (INS, 1994). Indeed, despite the variety of qualitative and quantitative restrictions placed on immigrants by dozens of U.S. laws since the late 19th century, the wives (and minor children) of U.S. citizens have never been restricted from immigrating, nor have husbands from Western Hemisphere countries.1 Under current law (the Immigration Act of 1990), as has been the case for three decades, immediate relatives of adult U.S. citizens (i.e., spouses, children, and parents) may enter without any limitation. (The best quantitative analysis of marriage and family ties in U.S. legal immigration flows remains that of Jassod & Rosenzweig, 1990; on marriage and kinship networks among undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Central America, see Chavez, 1992; Massey & Espinosa, 1995.)

TABLE 1.1

Family Connections: Immigrants Admitted by type of Admission and Sponsership 1993

Immigration to the United States is largely a family affair and probably will remain so for the future, regardless of the reforms and restrictions that are currently making their way through the legislative process in Congress and may soon become U.S. law. In the late 1980s the backlog for immigrant visas was such that, for some preference categories, the waiting line for applicants from main sending countries like Mexico and the Philippines extended to 10, 15, and even 20 years (cf. Rumbaut, 1991b). Susan Forbes Martin of the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform recently estimated that if someone applies from the Philippines today, it could take, preposterously, up to 43 years to obtain a visa! Simply eliminating the legal eligibility of close family members to immigrate may have the unintended result of creating new pressures and motives for illegal immigration. As Massey and Espinosa (1995) showed in a compelling analysis of determinants of migration from Mexico to the United States, reducing the supply of legal visas does not affect the volume of the migrant stream but simply channels a larger proportion of it into undocumented status.

To varying degrees of closeness, the more than 22 million immigrants in the United States today, to which can be added an even larger number of their U.S.-born offspring, are embedded in often intricate webs of family ties, both here and abroad. Such ties form extraordinary transnational linkages and networks that can, by reducing the costs and risks of migration, expand and serve as a conduit to additional and thus potentially self-perpetuating migration. Massey and his colleagues (1994) recently pointed to a stunning statistic (reported in Camp, 1993): By the end of the 1980s, national surveys in Mexico found that about half of adult Mexicans were related to someone living in the United States and that one third of all Mexicans had been to the United States at some point in their lives. By the same token, despite 35 years of hostile relations, it is my guess that perhaps a third of Cuba’s population of 11 million have relatives in the United States and Puerto Rico. The proportion of immigrants in the United States in 1990 who hail from countries in the English–speaking Caribbean, notably from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Belize, and Guyana, already constituted between 10% and 20% of the 1990 populations of their respective countries—a double-digit group to which can also now be added El Salvador (Rumbaut, 1992). Family connections in turn enhance the potential for further “chain” migration, both legal and extralegal. (On the family-reunification immigration multiplier among legal immigrants, see Jasso & Rosenzweig, 1986, 1989, 1990; Arnold, Cariño, Fawcett, & Park, 1989.) A recent report in The New York Times told about the tragic fate of a Chinese family from Chang Le, a town of 650, 000 in Fujian Province that is the source of most illegal Chinese immigration to the United States (which often involves incurring family debts of as much as $30, 000 to pay “snake–heads” [smugglers] for passage to New York City). According to the report, “nearly everyone in Chang Le… seems to have a relative or acquaintance who made the journey in the last five years” (Faison & Lii, 1995).

Such chaining processes often lead to remarkably dense ethnic concentrations in U.S. cities, consisting of entire community segments from places of origin and including extended families and friends, not just compatriots. In some cities in California and elsewhere, the links with particular towns or villages in Mexico go back generations and can be traced to the 1942–1964 Bracero Program or to earlier migration chains (see Alvarez, 1987; Massey, Alarcon, Durand, & Gonzalez, 1987). However, the process can take place very quickly. For instance, when Saigon fell in 1975, there were very few Vietnamese and virtually no Cambodians and Laotians residing in the United States, and in the absence of preexisting family ties, U.S. resettlement policy succeeded initially in its aim to disperse the Indochinese refugee population to all 50 states (“to avoid another Miami,” as one planner put it, referring to the huge concentration of Cuban refugees there). By the early 1980s about a third of arriving refugees already had close relatives in the United States who could serve as sponsors, and another third had more distant relatives, leaving only the remaining third without kinship ties subject to the dispersal policy (Hein, 1995; Rumbaut, 1995b). By 1985, 20% of the small Salvadoran town of Intipucá was already living in the Adams-Morgan section of Washington, DC, and had formed a Club of Intipucá City to assist new arrivals (Schoultz, 1992). Such spatial concentrations of kin and kith serve to provide newcomers with manifold sources of moral, social, cultural, and economic support that are unavailable to immigrants who are more dispersed and help to explain the gravitational pull exerted by places where family and friends of immigrants are concentrated (Portes & Rumbaut, 1996; Rumbaut, 1994b). In the process, as Tilly put it, immigrants create “migration machines: sending networks… articulated with particular receiving networks in which new migrants could find jobs, housing, and sociability” (1990, p. 90).

The import of immigrant family connections goes far beyond their functions for chain (or circular) migration and local support. Remittances (“migra–dollars”) sent by immigrants to family members back home (which, worldwide, according to a United Nations estimate, amounted to $71 billion in 1991, second only to oil sales) link communities across national borders and are vital to the economies of many sending countries.2 Remarkably, the survey of formerly undocumented immigrants who had resided in the United States since 1982 and who applied for legalization under IRCA found that the families of legalized aliens remitted about $1.2 billion to family members and friends outside the U.S. in 1987 alone. This figure represented about 7% of the family income, earned largely from low-wage jobs (INS, 1992). Across the border, one town of only 3, 500 in rural Mexico received over $1 million in U.S. remittances and savings in the year prior to a recent survey there (Massey & Parrado, 1994). Or consider the role of family ties in this other example: a decade and a half ago in Vietnam, ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese refugees were paying 5 to 10 gold pieces ($2, 000 to $4, 000) per adult to cross the South China Sea in flimsy fishing boats—a price well beyond the means of the average Vietnamese. To afford this often required ingenious exchange schemes through kinship networks. For instance, a family in Vietnam planning to escape by boat contacted another that had decided to stay to obtain the necessary gold for the passage; they in turn arranged with family members already in the United States (usually “first wave” refugees) for the relatives of the escaping family to pay an equivalent amount in dollars to the second family’s relatives (Rumbaut, 1991b). Similar exchange arrangements via family branches were developed by Soviet Jewish émigres who had been forbidden to take anything of value with them upon leaving the Soviet Union (Orleck, 1987).

That embeddedness in family, in a web of primary ties of affection, trust, and obligation—or what Bodnar described as “the ligaments of responsibility among kin” (1987, p. 72)—is at once a rich resource and a potential vulnerability. The family is, in Lasch’s (1977) memorable phrase, a “Haven in a Heartless World,” but it can sometimes be its headquarters. Family ties are a source of both positive and negative social capital (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993; see also Bertaux-Wiame, 1993; Coleman, 1988; Fernández-Kelly & Schauffler, 1994; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Tienda, 1980), that is, a resource that inheres not in the individual but in social (familial) relationships that can cut both ways, enabling as well as constraining particular outcomes. Family ties bind—and band, and bond, and bundle. The family is home, a place where, as Elizabeth Stone put it in her engaging study of family stories, “when you have to go there, they have to take you in” (1988, p. 21). It is the crucible of self and socialization, of character, conscience, authority and discipline, of our very names, linking us in a chain of being and meaning. But the family can also become the site for intense, deep-seated conflicts between spouses, siblings, parents, and children. Especially among immigrant families moving from one sociocultural environment to another, gender and generational role dissonance in rapidly changing marital and parent-child relationships can amplify and intensify conflicts and lead to family breakdown (Addams, 1910; Antin, 1912; Berrol, 1995; Child, 1943; Glenn & Yap, 1994; Grasmuck & Pessar, 1991; Handlin, 1951; Hein, 1995; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 1994; Kibria, 1993, 1994; Menjivar, 1996; Min, 1995; Rubin, 1994; Sung, 1987; Thomas & Znaniecki, 1958; Vigil, 1988; Wheeler, 1972). In given circumstances, however, because families are nested in and shaped by larger structural, cultural, and historical contexts, the shared adversity of the migration and subsequent adaptation experiences can motivate the family to close ranks cohesively and productively, honing in social solidarity an adaptive ethos of effort and efficacy and providing fertile soil for often remarkable achievement in the new country (Rumbaut & Rumbaut, 1976; see also Bodnar, 1987; Caplan, Choy, & Whitmore, 1991; Johnson, 1982; Suárez-Orozco, 1989; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 1995).

International migration entails more often than not a radical, engulfing, transformative process that profoundly affects and changes all who attempt it, including individuals, families, and societies. It is no mere coincidence that the words travel and travail share a common etymology (Furnham & Bochner, 1986, p. 63). The shock of such a journey depends to a large extent on the social distance traveled from origin to destination. At one end of the spectrum of migration contexts are the preliterate Hmong peasants from the Laotian highlands, who fled on foot in the aftermath of the Indochina War, crossed a jungle and the Mekong river, and were penned for years in Thai refugee camps before eventually resettling in megalopolitan California or Minnesota. A well–connected cosmopolitan English professional, job offer and visa in hand, who flies business class with ...