![]()

Part One: Building

Dynamic Stability

![]()

Section 1: The High

Performance Organization

![]()

1 ___________________________________

Introduction: towards the high

performance organization

Investors will reward a successful downsizing program, but they place a much higher value on companies that improve their bottom line by increasing revenues.

Pathways to Growth, Mercer Management

Journal, 3, 9 (1994)

In a fast-moving economic climate, organizations in every sector are having to change just to stand still. Against the backdrop of an increasingly volatile global economy, the focus of many business leaders and investors in recent years has become ever more short term. Increased global competition and the effect of customer choice are driving organizations to reinvent themselves and compete on the basis of speed, cost, quality, innovation, flexibility and customer responsiveness. Technology is leading to shorter cycle times, and new working patterns (such as sun-time working and teleworking) have been introduced in response to increasing consumer demands for cheaper, better, faster and round-the-clock availability of quality products and services. In this context, change-as-an-event is being replaced by change-as-the-norm.

The ability to manage continuous change has become the lifeblood of business success. However, it has also become the Achilles Heel for organizations unable to change fast and effectively. Unless an organization can flex in line with the changing needs of its customers and the driving forces in the environment, it soon finds itself out-of-step and forced to implement major ‘transformational’ change.

The challenge of managing change

Given the drivers for business flexibility, organizations need to change in order to remain successful. Change is not something to be managed just when there is a major crisis or when a new chief executive arrives and embarks on an ambitious change initiative, hoping to make his or her mark. Change management is an ongoing challenge and a prerequisite for organizational survival. What makes this a tough challenge is that, despite the sheer volume of change activity undertaken in recent years, the sad fact of the matter is that most organizational change efforts fail. Various reports suggest that 75 per cent of all transformation efforts fail, as do 50–75 per cent of all-re-engineering efforts. In mergers in particular, even those companies that manage to achieve short-term benefits from the integration usually fail to realize the longer-term value potential of the deal. Why should this be so, especially as it might be presumed that business leaders reach their positions on the basis of strong business judgement?

Several factors are known to contribute to failure, including inappropriate business strategies. Decisions can be made too late, based on faulty information, driven by egos or fad, or may simply be the wrong course of action for that time. What is becoming self-evident is that in a fast-moving economic climate, great business strategies alone are no guarantee of long-term success. The strategic planning timeframe has become very short term, with the challenge being less about choosing a strategic direction and more about implementing the latest chosen strategy.

However, most theorists now recognize that the main causes of failure are in the human domain. Change is a profoundly human process, requiring people to change their behaviours if the change effort is to be successful. The most effective change occurs when employees commit to the change effort. Resistance to change is common despite (or perhaps because of) people's familiarity with change. In today's workplace, people are expected to absorb large amounts of change without difficulty. Given the sheer volume of change activity, employees may experience multiple challenges – the need to master new skills, forge new relationships, even develop a new workplace identity. Essentially, managing change is about managing people through change.

In order for successful change to occur, employees need to be willing and able to adapt their behaviours and skills to respond to changing business needs. Organizations need to be ‘dynamically stable’ (Abrahamson, 2000). Ironically, the very process of changing can also destabilize the foundations of future success by destroying the currency on which employee motivation is based – trust. Successive waves of change – restructurings, redundancies, delayerings – have swept through organizations in recent years, leading to a severe erosion of the ‘psychological contract’ – the set of unwritten mutual expectations between employers and their employees. This represents a real threat and risk factor for continued business success since at the heart of the psychological contract is trust, which change research suggests can be a major enabler of change while, conversely, a low trust level is one of the greatest barriers to change.

The old relational contracts of the past, where employees expected continuity of employment and the possibility of promotion in return for unstinting loyalty and hard work, have largely been swept away. Notions of job security and conventional career growth have been replaced by messages about ‘employability’ at a time when many people have experienced increased workloads, uncertainty about pensions and a sense that their employer considers them to be an expendable ‘resource’ rather than a valued contributor.

Consequently, the psychological contract has become more transactional than in the past. Employees are more obviously taking responsibility for managing their own interests, including their career. Employees who believe themselves to be employable elsewhere do not place commitment to any one employer high on the agenda unless that employer offers something the employee values.

Ironically, in the emerging knowledge economy, where skill gaps exist and key employees with marketable skills are hard to find, the power balance is tipping in favour of employees, forcing employers to put the needs of employees higher up their agendas. Recruitment and retention (increasingly referred to as ‘talent management’) are becoming major challenges, and organizations are being driven to develop new and more meaningful relationships with such employees in order to recruit, retain and reap the benefit of the best available talent. I shall argue that it is in an organization's best interests to focus on building a partnership with employees on issues such as careers and work–life balance if the organizations themselves are to survive and thrive in future.

This highlights the paradoxical nature of change: without change an organization is likely to stagnate, yet the way the change process itself is handled can fundamentally undermine the basis of future high performance by damaging or destroying the employment relationship between employers and employees. Another paradox is inherent in the way most organizations function: managers aim to maintain and stabilize operations, rather than change them. For managers at all levels, managing change in ways that retain employee commitment, keep ‘business as usual’ going, yet produce new, value-added ways of operating, is a key challenge.

Attention is therefore shifting instead to building a more sustainable approach to change, based on organizational culture and reflected in management and employee behaviour and practice.

Types of change

Change is not uniform – there are many types of change producing different effects on businesses and their employees. For example, many employees will have experienced incremental change efforts aimed at improving current operations. The use of technology in particular has brought with it the demand for new skills, methods and working hours. Typical changes of this sort are the introduction of new IT systems, outsourcing, the increasing use of contractors, call centres, the introduction of flexible working, and virtual teams. Such changes require people to develop flexible mindsets and the willingness to learn and be able to work effectively in new working patterns and across organizational cultures.

Rather than leading to increased leisure hours, as was predicted decades ago, technology has added to workloads by enabling new working arrangements, the non-stop flow of e-mail traffic, and the removal of barriers of time and place. Work can be, and is often expected to be, carried out anytime, anywhere. At one level people seem to adapt relatively effortlessly to such changes. The sight of business travellers using mobile phones and laptops as they travel, downloading e-mails at every conceivable opportunity, is now commonplace. So too is the endless pressure to perform and, with it, the danger that life can become dangerously skewed towards continuous working patterns.

Many employees will also be familiar with the sorts of transformational changes needed when an organization falls out of step with its environment and needs to regain strategic alignment (sometimes requiring a new business model). Transformational change often tends to be driven by necessity rather than preference. It usually has an air of urgency about it, and can involve major restructuring, replacement of personnel, the selling off of some parts of the business or some other major strategic shift. For employees, such changes can present the challenge of coping with possible trauma during downsizings and readjustments to new working practices and jobs. They can also provide positive boosts to morale if transformation leads to new growth, energy and renewal for the organization and for individuals.

In addition, many employees will have experienced more radical forms of change, such as a merger or acquisition. Such changes force people out of comfort zones. Even employees from the acquiring company may find that the old pecking order is disturbed and that they have to start again to build relationships and re-establish themselves in the new scenario. In the public sector the need for ‘joined up’ delivery is bringing about many types of cross-organizational partnering, rather than full mergers. For some employees, working in strategic alliances, partnerships and joint ventures with other organizations offers unparalleled opportunities for personal development, as well as the challenges of working with ambiguity and retaining good ‘home’ connections while forging new relationships and directions.

What is clear is that change is not neutral in its effects on people. It tends to have an unpredictable impact that is both substantive and emotional. Managing change effectively requires more than an intellectual understanding of the processes involved. It requires, in the jargon of the day, real emotional, political and, some would argue, spiritual intelligence on the part of those leading change.

Change, productivity and performance

Despite the volume of change and the valiant attempts to reorganize to meet marketplace demands in recent years, many organizations find that sustainable business success remains as elusive as ever. In trying to understand why this should be so, we shall explore the link between change, organizational performance and business success. It is possible that, by ‘unblocking’ some of the perceived barriers to high performance, positive change will flow more freely, providing a better platform for business success.

For example, whatever the strategic drivers for change, if we look at the wave upon wave of initiatives of recent years, we are likely to find that change tends to be aimed at achieving immediate synergies and business improvements. Ironically, implementing change for short-term gain has proved the undoing of many a good company. This is largely because a short-term perspective on change tends to result from knee-jerk reactions to business pressures, or to the latest business fad. Constant and multiple change initiatives appear to take their toll on employees and the organizations that employ them. No sooner has one change initiative begun than another one gets under way. There is often little real communication about why change is taking place, and after a while no-one seems to bother to find out if the change is working. In consequence, change-weary employees lose sight of the goal, customer service standards suffer and disgruntled customers go elsewhere.

A law of diminishing returns

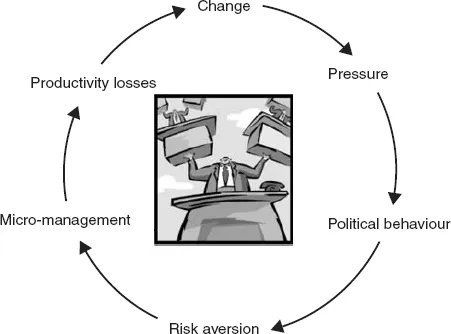

Looked at from an employee perspective, there can often appear to be little coherence between change projects or progress being made as a result of change. Instead, change seems to result in greater pressure on individuals as their workloads increase and targets become ever more stretching. Against a backdrop of uncertainty, company politics become an additional source of pressure as individuals strive to protect their own position. ‘Blame culture’ and scapegoating tend to lead to risk aversion. In such a context, it is hardly surprising that people dislike the increased levels of accountability and seek to pass the buck. Innovation, which requires a degree of risk-taking, seems unlikely in such circumstances.

In turn, managers, frustrated as employees’ lack of accountability, become less likely to delegate. Quite the contrary; they start to take back jobs, interfere and ‘micro-manage’. Rather than increasing productivity, this can actually contribute to productivity losses as work becomes centred on managers. At some point the system gives way and another change initiative begins in order to try and address the problems, so the vicious cycle begins over again. It is perhaps little wonder that so much change effort appears to achieve so little.

Figure 1.1 A law of diminishing retur...