- 418 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Early Professional Development for Teachers

About this book

Early Professional Development has recently been recognized throughout the UK as a key area for improving the quality of teaching and learning in schools. All teachers need support to move from novice to expert. Set out here is a range of articles to help them achieve that goal. Included are practical strategies for investigating classrooms, ideas about teaching and learning, and key debates concerning professional development, all selected with the aim of moving classroom practice forward. This book offers teachers the opportunity to explore the latest debates on professional development as well as providing practical tips for use in the classroom, and is a rich resource for those teachers committed to developing their teaching for the benefit of their pupils.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1

Teaching Early Professional Development: The Context

Teaching Early Professional Development: The Context

Chapter 1

Teacher Early Professional Development: The Context

Introduction

I was teaching about lenses, and I had taken my rather boisterous group of 14-year-old pupils outside on a sunny summer day to see whether they could scorch bits of scrap paper with a convex lens by focusing the sun’s rays. They had a good time, marvelled at the bright spot formed, asked interesting and pertinent questions and, after a while, we went back inside. We talked about how their ideas about refraction, covered in the previous lesson, applied to this shaped glass block known as a lens. As I turned round from the diagram we were jointly constructing on the board to continue the discussion with the class grouped near me around the front, I spotted the Deputy Head Teacher who had just come in and was leaning silently against the back wall. I finished off the diagram, concluded the discussion and wound up the lesson. The pupils left. ‘I came in earlier but it was like the Marie Celeste,’ he said. ‘We were outside,’ I replied. ‘Yes. That lot can be difficult, but if you can get them out, back and settled, there can’t be much wrong. Well done.’ ‘Thanks,’ I replied. He had watched me teach for about twenty minutes; it was the summer term and his only visit. That was it. I had just been assessed and passed my probationary year.

That story is true. It was how one of the authors passed an early and, in many ways, the most important ‘rite of passage’ as a new teacher in the mid-1970s. It was a successful personal outcome for the teacher in question but a totally unsatisfactory professional experience. Although the school was large and boasted its own ‘professional tutor’, the support and advice for new teachers was random, general and without any criteria for assessment other than ‘seems to survive’. Moreover, as no one knew any teacher’s individual needs, there was no continuity between receiving Qualified Teacher Status (QTS), the programme set up for the ‘probationary year’ and any strategy for further professional development. Except for certain exceptional schools and LEAs, the above tale of benevolent neglect was not an unusual experience at the time. Many of the current senior managers in schools will have been inducted into the teaching profession in a similar ad hoc way. Although the story, for that teacher, has a happy ending, life was not so sweet for a colleague who started at the same school at the same time. He failed his probation, and in the extension period struggled to restore credibility lost in the eyes of both staff and pupils. He eventually left the profession altogether. So much more could have been done to help both of these novice teachers, including the one considered ‘successful’, in the crucial early years of their careers.

How has the situation changed? In this chapter we will look at the current context for teacher Early Professional Development (EPD) at the start of the twenty-first century. We will consider the nature of the skills, knowledge and understanding needed by teachers and the practicalities of establishing activities to help them to develop professionally in the hectic environment of schools.

The Context of EPD

In 1972 the James Report launched the idea of the triple-I. Education and training for teachers was described as falling into three cycles, initial, induction and INSET. The notion of a continuum of professional development has, until now, remained a professional ideal. The journey is worth re-visiting.

By the 1980s, many initial teacher education courses could be described as taking a ‘knapsack approach’ to course content. The view was that new teachers were unlikely to get access to further information and support once they started teaching full time. Consequently, they should be introduced to a whole range of issues, techniques and information to stuff into their knapsack for future use. It was almost as if Higher Education Institutions (HEI) were attempting to cram a lifetime of learning into one short period, with little thought as to whether this was an effective model for teacher professional development. Schools, for their part, saw new teachers (including student teachers) as the carriers of new ideas and techniques. In the early to mid-1990s this ‘us and them’ view of teacher development – HEIs do the training, schools allow them to practise on their pupils – gave way to a ‘partnership’ model. In this model, the time spent in schools considerably increased and supervising teachers took on an active training role as ‘mentors’ (DFE, 1992). In most cases, in addition to coaching and support, this included assessment of practical teaching and sometimes of more knowledge-based aspects of the course (Bridges, 1993; Maynard and Furlong, 1993). In 1998, for England and Wales, the government set out the requirements for what should be covered in initial teacher education (DfEE, 1998). Although criticised for its ‘technical skills’ approach to teaching, the government circular did make clear what school/HEI partnerships should include in its teacher education curriculum. The school’s full role in initial teacher training was confirmed as a foundation stone of the new regulations.

The consequence of these developments during the closing years of the last century has been far reaching. Setting aside the controversy that has surrounded the movement of many aspects of initial teacher education and training from higher education to schools, particularly in relation to funding, workload and consistency, the major impact has been the recognition of schools as sites for professional learning. Partnership with HEIs in initial teacher training has meant a generation of teachers has been trained in mentoring skills. These skills in classroom observation, assessment, debriefing and target setting against standards are directly transferable to supporting colleagues in general.

Other regulations have drawn explicitly on this newly developed school-based expertise. The restoration of formal induction in England and Wales (DfEE, 1999) (a probationary period or formal induction was retained in Northern Ireland and Scotland) requires that newly qualified teachers receive appropriate levels of support from teacher colleagues. Teachers now enter the profession with a ‘career entry profile’ to form the basis of early professional development in the induction year. At a stroke a proper connection, based on individual learning needs, has been made between initial teacher training and induction. Elsewhere in the UK, the development of a coherent framework for teacher professional development has gone one stage further. In Northern Ireland, the initial, induction and EPD years were brought together in a common competence framework (DoE, 1998) which took the view that stuffing all expectations into the initial teacher education ‘knapsack’ was also not a sensible strategy. And now in England, Wales and Scotland too, an expectation of teacher continuing professional development will be put in place (DfEE, 2001; SEED, McCrone Report, 2000).

As yet there is no coherent framework that seamlessly supports a teacher through career-long professional development, from novice to expert teacher, from classroom teacher to subject leader to school leader (see Chapter 7 for a fuller explanation). But the signs are that coherence, entitlement and support are back on the professional development agenda, along with schools and classrooms as the site for professional learning and learning from each other as part of teacher professionalism. It seems likely that we are about to see the realisation of the James Report’s thirty-year-old professional ideal.

In this context, it is clear that early professional development, for many years the underdeveloped part of career-long teacher learning, needs to move centre stage. A focus on early professional development must be prioritised if teachers are to move swiftly towards expertise.

Teacher Skills, Knowledge and Understanding

What do successful teachers do? What knowledge and understanding do they draw upon? In what ways is an ‘expert’ different from a ‘novice’? Chapters 3, 16 and 17 explore these questions in detail.

Any group of experienced teachers can come up with a set of competences that describe what effective teachers should be able to do. They might be rather idiosyncratic and context specific, but for the group of teachers involved, they would be their view of ‘what teachers do’. For example, one academic published in 1995 a checklist for evaluation of initial teaching skills, setting out 143 questions to be asked when assessing a student teacher (see Williams, 1995). It is unsurprising that national governments should seek to identify the set of knowledge, understanding and skills that describe effective teaching. And once established as a consensus view, use these descriptors as the basis for a rational approach to planned professional development from novice to expert. However, the different UK government officials drawing up such lists took a different view of the role of a teacher and consequently different parts of the UK have different types of standards. Also, as the standards were set out at different times, there are certain mismatches. Teachers are expected to improve throughout their career, but the clear framework for progression they might look for is absent. Ann Shelton Mayes looks at this issue in Chapter 7.

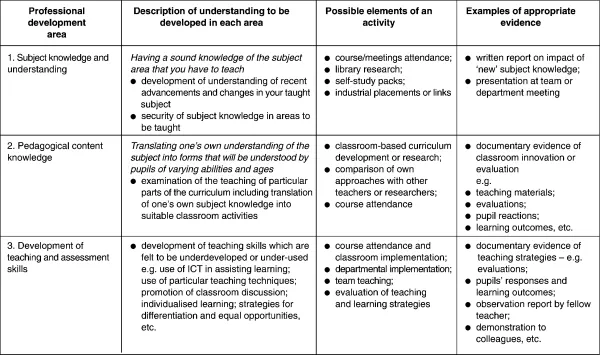

We may hope that the continual revision of standards will eventually lead to a rational framework for continued professional learning. But in the interim, there are thousands of teachers who complete induction each year and wish to focus on their own professional development. They need supportive frameworks for personal progress that help them aim towards excellence. Of course, in Northern Ireland such a framework already exists, at least in relation to the beginning years of early professional development. Elsewhere, in the UK, it has been the teacher associations who have focused on this neglected area for teacher professional development. The Association for Science Education (ASE), in particular, drew up a framework for Continuing Professional Development which classifies seven areas for development. The seven areas form a ‘professional development matrix’:

- Subject knowledge and understanding

- Pedagogical content knowledge

- Development of teaching and assessment skills

- Understanding teaching and learning

- The wider curriculum and other changes affecting teaching

- Management skills: managing people

- Management skills: managing yourself and your professional development.

(ASE, 2000)

Not only does this define what should be the focus of development for those in the first few years of their teaching career; it recognises the classroom itself as the site for learning and colleagues as key players in supporting professional growth. We look at this below.

Strategies for EPD

One of the first tasks of the newly established General Teaching Council for England was to set out recommendations for Continuing Professional Development for the profession.

The Council believes that an entitlement to learning and development time for every teacher in their second and third years of teaching should be established as a priority. The benefits of new entrants learning from one another and from more experienced colleagues should become one of the norms of professionalism. Entitlement to extended professional development time in the early years of teaching will:

- improve teaching and learning

- support a culture of extended professionalism in schools

- support retention.

The focus for these early years of professional development should be on engaging the individual teacher in reflection and action on pedagogy, the quality of learning, setting targets and high expectations, equal opportunities, planning, assessment and monitoring, curriculum and subject knowledge, and classroom management.

(GTC, 2000)

The ASE has developed a CPD model over a number of years which, in its focus on practical strategies for carrying out professional development activities, addresses the issue of ‘engaging the individual teacher in reflection and action on pedagogy’ in a meaningful way in the day-to-day turmoil of busy schools and classrooms. The model adapts well for teachers of any subject and phase in an early stage of their career.

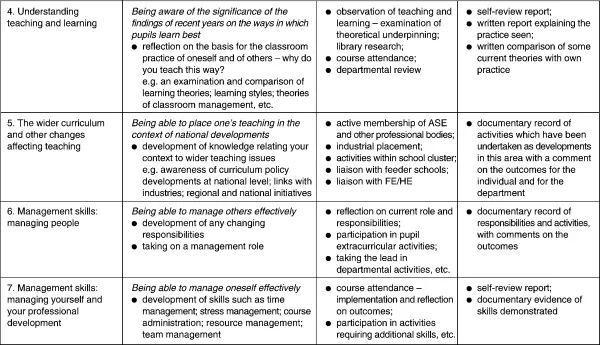

First, a further explanation of the seven aspects of the professional development matrix (adapted from ASE 2000). (See Figure 1.1 on pp. 10-11.)

Figure 1.1 The ASE professional development matrix

1. Subject Knowledge and Understanding

Few would disagree that a sound grasp of subject knowledge is fundamental to good teaching. But, to be truly good, teaching should also demonstrate an enthusiasm for the subject. Pupils and some teachers talk about boring topics. We believe that the problem is often not the topic but the teaching. Enthusiasm cannot be maintained where a teacher is unsure of the material.

Common consequences of unsound subject knowledge are hesitancy in teaching, a lack of direction to the lesson and a lack of clarity in explanation. Over-reliance on books and worksheets as the primary sources of the information for the pupils is another outcome. Having a sound subject knowledge allows us to relax with pupils, ask pertinent and interesting questions which offer an appropriate challenge, respond to a wide range of questions from pupils, react positively to the unexpected and happily confess to not knowing a particular answer. It does not follow that we should all possess the same range of knowledge; although the introduction of the National Curriculum in schools and for ITT (Initial Teacher Training), in core subjects, does mean that we are moving to a position where a common minimum range is expected for primary teachers and secondary teachers of a National Curriculum subject.

In early professional development, we are looking for evidence that subject knowledge has been extended and/or deepened. It is something that all of us have to do and the means by which we can do it are varied. For a teacher in the early years of his or her career preparing to teach a new topic is the most common way of improving your subject understanding. We need to explore ways of maintaining and developing subject knowledge through personal study, learning from colleagues and the use of ICT.

2. Pedagogic Content Knowledge

Subject knowledge is a personal attribute, built up over many years and is being constantly reworked no matter how experienced we are as teachers. Once we feel secure in that understanding, we are then in a position to transform it so that it is appropriate for the level of understanding of a particular group of pupils. This is the key skill of the successful teacher. It is a complex procedure but essential to the teaching task. It involves a range of strategies to manipulate and transform personal understanding of a topic into a fo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Early Professional Development for Teachers

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Section 1: Teaching Early Professional Development: the context

- Section 2: Teaching for Learning

- Section 3: The Classroom Teacher and School-based Research

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Early Professional Development for Teachers by Frank Banks,Ann Shelton Mayes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Counseling in Career Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.