This section presents the theoretical underpinnings of family-centered care in bereavement. We examine the nature of family grief, family systems theory, and models of family therapy, whether delivered in bereavement or for loss experienced by families when a member has a physical or mental illness. We conclude with the ethics of family bereavement care, which are central to every clinical approach.

Sophie was just 15 in 1877 as she lay listlessly on her bed, dying from consumption, the archaic term for tuberculosis. Beside her were her brothers, Edvard, 14, and Andreas (known within the family as Peter), 12; and sisters, Laura, 10, and Inger Marie, 9. Befitting the mournfulness, the children’s father, Christian, and their aunt, Karen, led them in prayer. Early death was not unfamiliar to this family: tuberculosis had laid claim to their mother the very year when Inger Marie was born. Although Christian was a physician, he could not thwart the ravages of nature such as the “white plague” of tuberculosis that afflicted his wife and children. Times were harsh. The Norwegian capital where they lived, Kristiania, later called Oslo, suffered extremely bleak winters. And it would be some years before the discovery of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by Robert Koch in 1882, and another half century before effective treatment became available to prevent a death scene such as this.

Grief in the Family of Edvard Munch

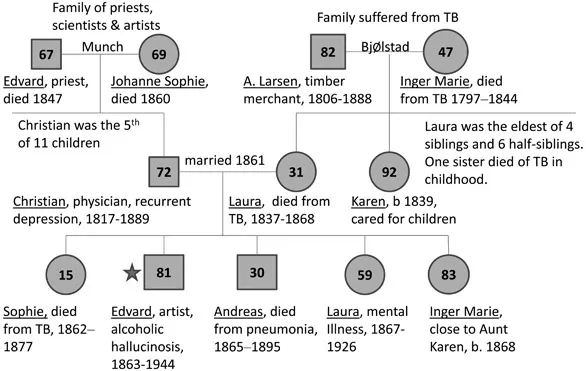

This was the family of the expressionist artist and lithographer Edvard Munch (1863– 1944). He himself was sick for much of his childhood, undoubtedly also afflicted with consumption. To occupy long days spent at home, he learned to draw, sketching medicinal bottles, room interiors, and even Sophie, unwell in her bed. This love of art was bred in the family (see Figure 1.1). His paternal grandfather’s first cousin, Jacob, had been a respected artist, and Edvard’s mother and older sister encouraged his childhood drawing. By age 13, Edvard, who had viewed works by the Norwegian landscape school, was already practicing by copying their paintings.

Edvard’s mother, who had seen one of her sisters die from consumption during childhood, was likewise unwell for much of her married life. Readily fatigued and rendered breathless by short moments of exertion, she sat for extended periods in an armchair by the window. With the birth of each of her four children, her health became more fragile. Expecting that her days were numbered, she wrote her children a letter (now held in the Munch Museum), expressing her love and exhorting them to sustain their faith and trust in God. Munch’s papers include an account of his memory of his dying mother, which one biographer, Sue Prideaux, described as revealing through this period his inner “emotional chaos” (Prideaux, 2005, p. 330, note 318). Edvard’s account, however, was necessarily limited: in accordance with the custom of that era, the children were dispatched to a neighbor’s house while their mother was buried.

Figure 1.1 Genogram of the family of the expressionist artist Edvard Munch * (1863–1944) showing the extent of physical and mental illness, with Munch’s resultant cumulative exposure to death and grief. Edvard’s mother died when he was 5, Sophie when Edvard was 14, Christian when he was 26, and Andreas when he was 32, while his sister Laura was mentally ill for many years.

Munch’s father, Christian, was the son of a priest. Christian’s family had lived in poor parts of rural Norway, where education, particularly the study of history, was highly regarded. So was religion, and the family—which included Christian’s uncle, a bishop and poet—was devout. Christian considered his bouts of unhappiness to be sins of ingratitude for all that God had given him. The death of his wife after just seven years of marriage brought deep grief and worry about how he would care for their five children. Christian became more fervent in his piety and often told the youngsters that their mother was watching over them from heaven. Fortunately, Aunt Karen, his wife’s 29-year-old single sister, was able to move into the family home to help raise the boys and girls.

Always addressed by the Norwegian title Tante Karen, she was devoted to the children and brought joy and nurturing into an otherwise sad household. The younger siblings thought of her as their mother, but Sophie and Edvard turned to each other for security and companionship. Because both were ill, they spent extended periods home from school together. Sophie encouraged Edvard’s drawings; their bond became deep and strong.

Sophie’s death was therefore life-impacting for Edvard, who lost in his big sister, his soul mate and maternal imago. At age 14, he understood her decline and witnessed his father’s distress and impotence at her wasting away into death with a hacking cough, fevers, profound weakness, and eventual delirium. This time, Edvard attended the funeral. Even so, his diary remains silent about his feelings, which were repressed for many years. Eventually, his grief was expressed through his painting.

Tuberculosis was not the only affliction that was prominent in the family; so was mental illness. Christian suffered from recurrent bouts of depression, while Edvard’s younger sister, Laura, was hospitalized for an extended sickness involving periods of catatonia, hallucinations, and chronic insanity. Eventually, she died from cancer. In 1895, Edvard’s brother, Peter, succumbed to pneumonia at the young age of 30. The only one of the siblings to marry, Peter left behind a pregnant wife. Munch himself, during his middle age, deteriorated into periods of heavy drinking, necessitating an eight-month hospitalization for alcoholic hallucinosis.

At age 16, Edvard studied engineering at a technical college, learning to draw to scale and in perspective. But by the time Edvard was 18, art won through as his career choice, and he enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design of Kristiania. Although his morbidly pious father continued to provide a small allowance, he harshly condemned Edvard’s drinking binges. More significantly, his father, who deplored the influence of the bohemians upon his son, even destroyed Edvard’s early nude paintings. It was Edvard’s art teacher, Christian Krohg, who nurtured his confidence and affirmed his talent to portray the deep emotional tone of whatever he painted. At age 23, Edvard described in his diary his image of his favorite sister, Sophie, The Sick Child (1886), as his first “soul painting” (Prideaux, 2005, p. 83). His efforts finally paid off when a state scholarship to study art led him, then 26, to move to Paris in 1889. However, his father’s death later that year forced Edvard’s return to Oslo, and thereafter he supported his family. Grief with its deep suffering had returned to his family of origin.

Edvard’s art similarly captured in poignant color the devastating emotions he both witnessed around him and felt personally. Melancholy, sickness, existential angst, and soul pain! Each face and bodily pose on his canvasses depicted the state of mind of those about him. His great 1895 canvas, Death in the Sickroom, portrayed the varied, yet heart-felt responses of his family struggling with loss as death fell, yet again, upon another family member. Their mournfulness was an intensely felt family sorrow.

Munch’s grief was undoubtedly pathological, given its chronicity and impact on his life. Preferring to withdraw from others, he retreated for extended periods. He assuaged his wretchedness with bouts of heavy drinking, whether absinthe, whiskey, or wine. Choosing not to follow the impressionist art of that era, he turned to paint from the soul, reworking for many years his mental images of the death room. Aunt Karen became a loyal and supportive presence, sitting for many hours as the model for his grieving mother figure. His records show that he reworked the painting of The Sick Child numerous times, a pieta of a “dying child and anguished mother” (Prideaux, 2005, p. 86). Munch’s relationship with Tante Karen deepened, and, in later years, he would write to her regularly, share all his concerns, and come to trust her deeply. They exchanged sums of money to help each other through phases of poverty. As Munch eventually became successful, he loyally supported his family.

But family was not Munch’s only source of love. Munch had two romantic loves, Millie and Tulla. Millie was the passionate belle of his early adulthood, appearing in many paintings of love, dancing, jealousy, and the femme fatale. This first relationship broke up consensually. He later fell in love with Tulla and traveled with her to Italy. She sought marriage, but his memories of sickness and the pain of loss from his childhood led him to fear this commitment. Eventually, Tulla tired of his avoidance and chose instead to marry another friend. Humiliated by her decision, Munch turned again to drinking. Fighting with Tulla was sometimes dramatic: during one skirmish, a gun misfired, causing Munch to lose a finger. As he drank more heavily, he became paranoid with auditory hallucinations, necessitating hospitalization for six months in 1908.

Upon recovery, Munch chose a more solitary life. In 1909, he bought an 11-acre property at Ekely, outside of Oslo, where he spent much of his remaining life. He kept many of his paintings, woodcuts, and lithographs. A cherished, sentimental possession was the wicker chair that his sister Sophie had sat in beside her bed. It served as a linking object that he long treasured.

Clearly, Munch experienced much grief throughout his life, which he portrayed so poignantly on his canvasses. Today, as we view these works in art galleries and museums, we recognize that he knew the nature of family grief.

The Theory of Family Grief

Loss, death, and mourning afflict not only each bereaved person, but the pain reverberates among the clan. Too often the clinician focuses on the individual—the patient who presents on that particular day. The bereaved spouse seeks solace; the mother laments the death of her child. It is easy to respond to whoever appeals for help. Yet invariably, the family constitutes the fundamental context in which bereavement occurs (Kissane, 1994). Most importantly, the family influences the pattern of mourning that unfolds through its traditions and pursuit of religious, cultural, and ethnic norms. Family leaders may dictate what to do, when to be stoic, when to shed tears, and how to comfort one another. Curiously, the script that the family follows can be recognized from generation to generation, fostering either compassionate support or avoidant silence, depending on their custom.

In Munch’s family, their Christian religion provided a schema that deemed death to be God’s will, circumstances to be accepted in faith, with hope for a heavenly reunion. The related piety required stoic acceptance and moderated any emotional expression. Moreover, children were to be protected from overt emotional display. They were sent away to save them from witnessing adult distress. The family rallied with loving intent, and a devoted sister like Tante Karen sacrificed her personal future for the sake of her deceased sister’s children. Practicality prevailed! But the empathic support that might permit ready expression and sharing of feelings was replaced by a more rigid oppression and fundamental religious stance that had been accepted across several generations.

The face of the artist, Edvard Munch, is blank across many works of his family gathered around the deathbed. His father prays fervently; his aunt nurses the sick. His younger sisters are disconnected—one saddened with lowered head, the other staring off into the distance. Edvard’s brother awkwardly holds the door, seemingly anxious to escape. Here we see the differential responses within the group, the dominant sense appearing centrifugal, allowing bewilderment and suffering to be privately contained despite the presence of each other. No perception of mutual support can be found in these paintings. Albeit an unconscious process, a pattern of family response style is nonetheless apparent—and the historical data suggest that it is maladaptive.

Edvard’s early grief is complicated with avoidance, chronicity, inertia, and melancholy. He sits alone by the shore, sometimes gazes out the window from a darkened room, and paints self-images accompanied by a skeleton arm. Instead of his family uniting supportively, the outward force drives them into isolation. Edvard suffered ridicule by fellow artists whose canvasses were awash with the color and the beauty of nature. His world was a stark, threatening commentary on the harshness of life, replicating the silence of his family of origin. His realism confronted, frightened, and was unwelcome by non-comprehending critics in his social milieu. His only retreat was to pursue another escape—the carefree attitudes of the bohemians, albeit without healing.

Range of Family Responses

Families are greatly influenced in their response to loss by (1) their culture, its customs and taboos; (2) their immediate experience of the loss (whether anticipated, traumatic, stigmatized, or unexpected); (3) familial traditions that have encoded a pattern of response across the generations (either comforting or avoidant; distorting via blame, idealization, fear, or fatalism; or prolonging via memorialization and “stuck-ness”); and (4) their support network, which either connects or alienates (Kissane, 1994). Although individuals within a family will differ in their emotionality—for instance, mothers may be more expressive than fathers—the family as a whole guides the gestalt of the members’ response style.

It is up to the clinician to interpret how a response style is adaptive, drawing upon the strengths of the family, or how it proves restrictive, hindering healing and resumption of a creative life. The adaptive response promotes mutual support and comfort, with open sharing of thoughts and feelings, and trust in one another’s willingness to listen and help. It is built on a deep level of commitment found in the bonds of the family. The cohesiveness of the family and its ease of communication prevail. In contrast are families that block communication, blame one another, and, in the process, become conflictual, fractured, and distant. These families reveal a dysfunctionality that potentially harms a natural mourning process. Clinicians need to guide the development of management plans and supp...