- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Luxor And Its Temples

About this book

First published in 2005. This work, while aimed at a general audience, is by no means a dreary introductory textbook. Blackman perceptively answers the reader's most pressing questions about life in ancient Thebes, providing not only an informative text but also an engaging story. Topics covered include life in ancient Luxor, how Thebes became the capital of Egypt, poems, songs and romances, and great kings in time of war.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

LUXOR AND ITS TEMPLES

CHAPTER I

LIFE IN ANCIENT LUXOR

THE first question that anybody would ask who wanted to know something of the life led by the ancient inhabitants of Luxor—or Thebes as it was called by the Greek and Latin writers-would in all probability be : “What sort of houses did they live in ?” So I propose to begin the first chapter of this book by giving as briefly as possible what will, I hope, be a satisfactory answer to this by no means unintelligent question.

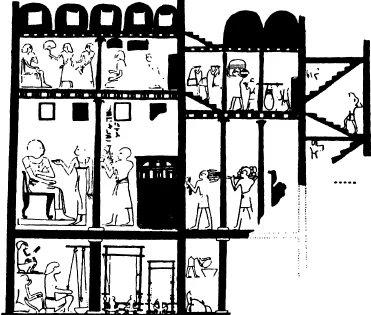

Excavations have shown us that an Egyptian town presented much the same appearance in ancient as in modern times. There were the same narrow streets and the same sort of houses, the latter constructed of mud-brick, sometimes whitewashed or colour-washed, and consisting, in the case of well-to-do folk, of a ground floor and one or two upper stories. A painting in the tomb chapel of a certain Theban royal scribe named Ḏḥutnūfer, who flourished some time about the year 1450 B.C., depicts just such a two-storied house, that of the royal scribe himself (see Fig. 1). It will be seen that flights of stairs lead from one floor to another and on to the flat roof, where, as at the present day, are placed domed granaries made of mud. No doubt, then as now, alongside of the granaries was stacked the household fuel—bundles of brushwood and maize-stalks and cakes of cow-dung. The roof in ancient, no less than in modern, Egypt was the women’s favourite resort, the place where they not only gathered to gossip and enjoy the air, but also to do a great deal of their work, spinning, sewing, and even cooking.

The ground floor of Ḏḥutnūfer’s house, it will be seen, is given up to the kitchen, and also to workrooms, where men and women are engaged in spinning and weaving. These workpeople are either members of Ḏḥutnūfer’s household, or else that individual let out the greater part of the ground floor of his house to a weaver, who used the rooms as his business premises.

On the first floor were Ḏḥutnūfer’s own apartments, where he also received his friends. The women’s quarters, as in a modern Egyptian house, occupied the top floor. It will be noted that the actual rooms shown by the artist are of fine dimensions, the ceilings being supported on columns, doubtless made of wood.

Fig. 1.—Ḏḥutnūfer’s House.

(After “Ancient Egypt,” iii. By the courtesy of Professor Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie.)

In respect of its furnishing and decoration, such a house as that of Ḏḥutnūfer would, though less magnificent, have been very much like one of the larger mansions now to be described.

The excavations of the Egypt Exploration Society and the Deutsche Orient - Gesellschaft at El-Amarna have laid bare the remains of some once splendid houses, doubtless similar to those that belonged to the great nobles and officials of ancient Luxor, and resembling in many respects the dwellings of the great pashas and beys of to-day. Such houses stood each in the midst of an enclosure, often covering a large area, surrounded by high, sometimes crenellated, walls of crude brick (see Fig. 4). To this enclosure admittance was gained from the street by an imposing gateway, outside which, on a couple of low brick benches, sat a small group of servants, whose business it was to supervise the ingress and egress of members of the household and of clients, and to attend to the wants of visitors. Such a group of servants is regularly to be seen sitting beside the entrance to a pasha’s residence in modern Cairo.

In one corner of the enclosure were the great man’s stables, cowsheds, storehouses, and granaries—for wealth in those days consisted not in money but in produce—and close to them the quarters of the male servants. In an entirely different part of the grounds was the residence of the wife’s female attendants and those ladies who found favour with the master of the house, but did not hold the privileged status of wife. It was to such ladies, no doubt, who, however, occupied a recognized position in the household, that the euphemistic title of “sisters” was assigned.

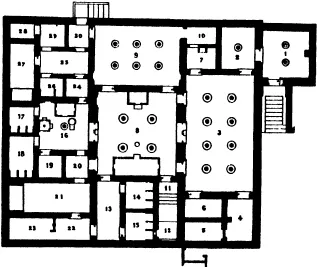

The actual mansion—a ground plan of a typical El-Amarna house appears as Fig. 2—stood in the middle of the enclosure, and a flight of shallow steps led up to the front door. On the ground floor were a number of fine rooms, the ceilings, painted bright blue, resting upon wooden columns, which were also painted in gay colours. The walls of these apartments were white, except for a painted frieze, which generally took the form of floral garlands or festoons, a bunch of dead waterfowl being occasionally represented hanging head downwards between each pair of festoons, a foretaste of the still-life pictures of the seventeenth century Dutch painters ! Sometimes, too, the wall-space of these rooms was broken by a painted recess, or a couple of such recesses, resembling somewhat the ḳibleh in a mosque, and perhaps serving a religious as well as a decorative purpose.

Fig. 2.—Ground Plan of a Mansion at El-Amarna.

(After “Journal of Egyptian Archœology,” viii. By the courtesy of Professor Peet and Messrs. C. L. Woolley and Newton.)

Of the pillared apartments, one generally lay on the north side of the house (Room 3 of the plan) and one on the west side (Room 9), the northern room being a favourite resort in summer and the western in winter. These two rooms had large windows down one wall—the outside wall of the house in either case—filled with stone gratings, which broke up the strong light in an agreeable manner.

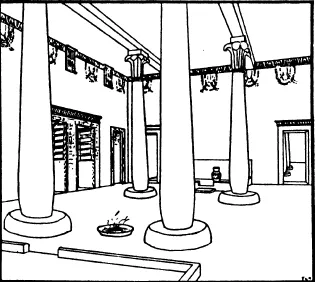

Between these two apartments, the north and west galleries, as they might well be called, lay two other pillared rooms, evidently reception or dining rooms, the one (Room 8) probably intended for the entertainment of guests (see Fig. 3), and the other (Room 16) reserved for the use of the family. In either dining-room there was a dais, on which possibly were placed chairs for the master of the house and for the principal persons among those who partook of a meal in his company. There was also a stone platform, built against one of the walls, with a stone screen at the back, and on this people performed their ablutions, for the ancient Egyptians indulged in a great deal of rather elaborate washing both before meals and at other times. A hollow was cut in the platform to receive the large jar which contained the ablution water. The jar is shown in the adjacent cut (Fig. 3) standing in position.

Fig. 3.—A Pillared Reception Room.

(After “Journal of Egyptian Archœology,” viii. By the courtesy of Professor Peet and Messrs. C. L. Woolley and Newton.)

These two dining-rooms were lit by grated windows set high up in the walls, and their ceilings rose well above the roof of the upper-story rooms, which did not extend above these two apartments. In the dining-room used for guests were a number of doors, including two fine folding doors, admitting to the two pillared galleries, the private dining-room and other rooms, and also to the staircase leading to the upper floor.

In either dining-room there was a receptacle in the floor for the portable hearth or brazier, which, as in the modern Egyptian house, was used in the cold weather, the fuel employed being charcoal.

The rest of the ground floor was taken up by two bedrooms (Rooms 21 and 27)—the bed standing on a low dais in a recess—and a number of smaller rooms. These and the bedrooms had no windows, and light could only have been admitted through the doors and through gratings above the doors. But whatever light managed to get in was intensified by the whitewashed walls. It should be noted that either bedroom had a bathroom and lavatory attached to it (Rooms 22, 23, and 28, 29).

Some of the smaller rooms (Nos. 14, 15, 17, and 18) were certainly store-rooms, being furnished with broad shelves placed on brick supports. The rest may have been used as sleeping apartments by less important members of the household, relatives and confidential servants. The kitchen was a separate building all to itself.

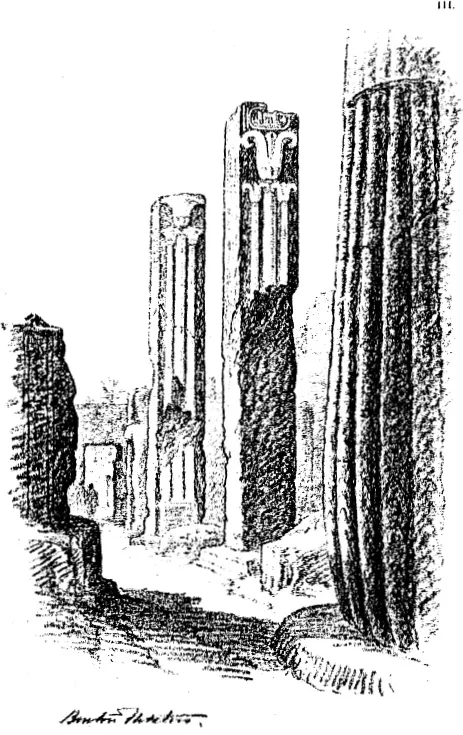

FLORAL COLUMNS, KARNAK.

Erected by Dhutmose III. One showing the papyrus plant of Lower Egypt, and the other the lilies of Upper Egypt. (See p. 58 foll.)

There was at least one upper story, which was probably given up entirely, or in the main, to the women. Certain of the upper rooms were pillared like those downstairs.

Such a house was beautifully though simply furnished. The floors of the principal rooms, which were of unburnt brick or tiles, appear to have been covered with matting, on which brightly coloured rugs or carpets were also sometimes laid. Occasionally such covering was dispensed with and the floor was painted, though never, so it would seem, with the beautiful designs, described in Chapter III., which were employed for the decoration of the floors of the royal palaces.

The more important rooms no doubt contained a number of chairs and stools, the best of these being made of ebony, or other precious woods, inlaid with ivory; or else the wood was overlaid with gold and sometimes inlaid as well with richly coloured glaze plaques. The chairs and stools often had seats woven out of palm-leaves, looking exactly like the cane seats of our modern chairs, and on these were laid cushions covered with leather or some woven material.

People reposed at night on couches, the legs of which, as also the legs of the chairs, were carved in semblance of those of a lion.

Other articles of furniture were boxes and caskets, often elaborately carved, gilded, and inlaid, in which were kept clothing and jewelry.

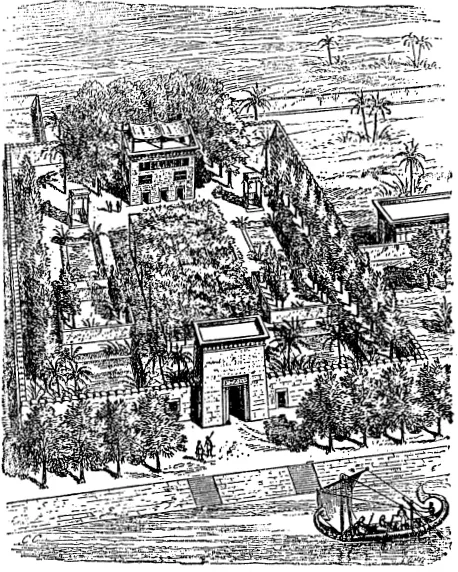

A large portion of the enclosure surrounding a great house was laid out as a formal garden (see Fig. 4). Part of such a garden was often, as in modern Egypt, given up to trellised vines, the remaining space being occupied by ornamental and fruit-bearing trees. There was also generally a pond in the garden, sometimes more than one, overshadowed by clumps of papyrus and other swamp-loving plants and bushes. In the pond itself grew lotus flowers, among which swam duck and other water-fowl, and also all manner of fish.

A love for nature animate and inanimate seems to have been a marked characteristic of the ancient Egyptians. A wealthy man gathered into his garden all the plants and flowers he could obtain; indeed, as we shall see in a subsequent chapter, certain of the Pharaohs brought strange trees, shrubs, and plants from abroad, and planted them in the gardens and parks attached to the royal palaces and the temples. Near the pond or ponds in the garden a gaily painted wooden pavilion was often erected, in which the master of the demesne could sit either alone or accompanied by wife and friends, and unobserved watch the antics of the water-fowl as they swam and dived among the water-lilies, preened their feathers on the bank, or sat in their nests amid the reeds. This love of the Egyptians for nature appears in the floral wall-decorations in their houses, but especially in the paintings and reliefs with which they adorned their tomb-chapels and the royal palaces.

Fig.4.—A House in its Surrounding Grounds.

(After Perrot and Chipiez, “Histoire de l’ Art dans a l’ Antiquité.”)

It was not in his garden only that the Egyptian gentleman practised the cult of the open-air life. Among his favourite pastimes were fishing and fowling, and hunting the hippopotamus, in backwater, swamp, and river, and big-game shooting in the desert.

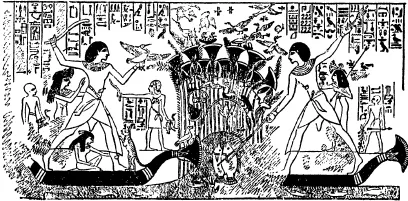

When fishing for sport the ancient Egyptian generally employed a double-bladed harpoon, and the artist, who represented his patron indulging in this form of amusement, always flatteringly shows him, as in Fig. 5, just in the act of hoisting his harpoon out of the water with a great fish transfixed on either blade ! When wielding this formidable-looking weapon the noble or gentle harpooner stood in the middle of a boat made of papyrus reeds cunningly fastened together. He is always depicted accompanied by one or more male attendants, often a son or two as well, and nearly always one or more of his ladies—his wife and a daughter or two. He used a similar boat and was similarly accompanied when he was fowling. Standing in the middle of the frail-looking craft (see Fig. 6), we see him hurling his throw-stick at the cloud of birds hovering above the dense papyrus thickets, which grow down to the water’s edge.

Fig. 5.—Egyptian Gentleman Fowling and Fishing.

(After Wilkinson, “Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians.”)

Sometimes when out for a day’s fowling the ancient s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Table of Dates

- Chapter I Life in Ancient Luxor

- Chapter II How Thebes became the Capital of Egypt

- Chapter III Thebes, the World’s First Monimental City

- Chapter IV Some Great Kings in Time of War

- Chapter V A Famous Queen

- Chapter VI Poems, Songs, and Romances

- Chapter VII Some Funerary Temples

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Luxor And Its Temples by A.M. Blackman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.