This is a test

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

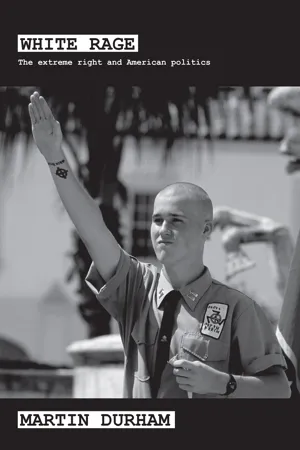

White Rage examines the development of the modern American extreme right and American politics from the 1950s to the present day. It explores the full panoply of extreme right groups, from the remnants of the Ku Klux Klan to skinhead groups and from the militia groups to neo-nazis.

In developing its argument the book:

- discusses the American extreme right in the context of the Oklahoma City bombing, 9/11 and the Bush administration;

- explores the American extreme right's divisions and its pursuit of alliances;

- analyses the movement's hostilities to other racial groups.

Written in a moment of crisis for the leading extreme right groups, this original study challenges the frequent equation of the extreme right with other sections of the American right. It is a movement whose development and future will be of interest to anyone concerned with race relations and social conflict in modern America.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access White Rage by Martin Durham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Before Brown

There is no one moment that the modern extreme right came into existence. But the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision on Brown v. Board of Education is crucial. In deciding to rule that segregation in schools was unconstitutional, the Court not only struck a death-blow against the way in which the white South had organized relations between the races. It was crucial to the rise of the Civil Rights Movement. It was central to the future of both the Democratic and Republican parties. It was key too for the extreme right.

Defined by the centrality they gave to race, extreme rightists could not but react vitriolically to a Supreme Court decision that ruled that whites and blacks should no longer be educated separately. Within five years, not only had the oldest racist organization, the Ku Klux Klan, revived but new extreme right groupings had emerged. In the years that followed other groupings have sprung up, and in the following chapters we will be examining a wide range of organizations. We will be exploring the strategies they have forged and the issues they have taken up, and will argue that it is not only the organizational landscape of the extreme right that has changed since Brown. In important ways, how it sees the new order of the future and how it proposes to get there is new. But it is not wholly so. It has inherited much from the extreme right of earlier years. In this chapter, we will be particularly concerned with organizations and issues of the earlier decades of the twentieth century. But we also need to go back further, and it is to the original Ku Klux Klan that we should first turn.

The Klan first emerged in the aftermath of the American Civil War. Created in Pulaski, Tennessee, it was set up as a social club by a group of former Confederate soldiers. Named after the Greek for circle (kyklos) and the Scottish word, clan, the club initially dressed up in hoods and cloaks and carried out pranks. But politics soon intruded. The victorious Union had not only ended slavery but was now engaged in an attempt to remake Southern society. Just as with the Brown decision almost a century later, Reconstruction led to widespread white resistance, and the Klan rapidly became a vigilante body. Hooded night riders attacked ‘impudent negroes and negro-loving whites’, inflicting beatings and carrying out murders. In 1867 the Klan was organized into an ‘Invisible Empire’, in which each state was led by a Grand Dragon and the role of emperor was taken by a Grand Wizard. Its campaign of terror was not without dangers for the organization, and in 1869 the Grand Wizard, General Nathan Bedford Forrest, declared that in some localities the Klan was being ‘perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes’. He decreed that ‘the masks and robes of the Order’ should be destroyed. Klan activity, however, continued. In 1871 Congress passed legislation forbidding ‘two or more persons’ from going in disguise to deprive others of their rights. Mass trials resulted in the conviction of many Klansmen, and the organization effectively ceased to exist. But Northern enthusiasm for Reconstruction also passed away, and by the end of the century Southern blacks were disenfranchised, while a rigid system of segregation ensured that in education, hotels, public transport and much else the two races were kept apart.1

The Klan declared that its ‘fundamental objective’ was ‘the MAINTENANCE OF THE SUPREMACY OF THE WHITE RACE’, and the segregation that came to define the South assumed that whites were a more advanced race.2 In the North, a more informal segregation kept white and black apart. But here, other conflicts took on importance.

Before the Civil War, nativist organizations had emerged, declaring that the United States was a Protestant nation. Catholic immigrants were accused of taking jobs and adhering to a religion which was antagonistic to liberty. But nativism was not solely opposed to Catholics. It privileged ‘Anglo-Saxons’ over ‘the dregs of foreign populations’ it saw as threatening America, and was as capable of being turned on non-Catholic Europeans as it was on Chinese or Japanese. Having declined with the rise of the conflict between North and South, nativism revived in the 1880s, but by then hostility to ‘Dago and Pole, Hun and Slav’ was not only accompanied by hostility to Orientals, it was coming to be joined by yet another antagonism, anti-Semitism.3

As with opposition to Catholic immigration, opposition to the entry of Jews revolved in large part around rivalry for jobs and for housing. It had a religious element too, focused on the belief that the Jews were Christ-killers. But it had a distinctive economic component, centred on the belief that it was Jews that controlled the centres of finance, and it was this conviction that showed itself in a movement that appealed particularly to beleaguered farmers in the late nineteenth century, Populism.

This movement had a number of different faces, and historians have disputed the degree to which it was affected by anti-Semitism. What is clear, however, is that at least some of Populism’s attacks on international finance were suffused with images of the Jew as exploiter. One writer, Ignatius Donnelly, was not only the author of much of the People’s Party’s 1892 platform but had shortly earlier written a novel vividly depicting Jewish oppression of American farmers. Other accounts of the depradations of Jewish bankers appeared from Populist publicists, and one account of the 1896 Populist convention commented that one of its most striking characteristics was ‘the extraordinary hatred of the Jewish race’.4 As we shall see, attacks on Jewish bankers would be crucial to the later extreme right. But so would other antagonisms. In the early twentieth century, opposition to immigration intensified. It was, however, going through important changes. In part, this was linked with the rise of eugenics, the claim that in a world in which nations were increasingly in conflict, the greatest danger was the failure to reproduce of the ‘fit’ and the multiplication of the ‘unfit’. For some eugenicists, the most important conflict was between white nations and ‘the rising tide of color’. But there was anxiety about divisions among white nations too, and for writers such as Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, those of Nordic stock stood higher than other Europeans. Earlier immigration restrictionists had claimed that America was Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. The new restrictionism was racial, but exactly who would be counted as within the favoured race was still uncertain. Nor was race the only antagonism that we should consider.5

Already in the 1880s, opposition to labour militancy had been connected with opposition to immigration. Nativism and anti-socialism came together dramatically during the First World War. Ultra-patriotic groupings denounced socialists as disloyal. The attack was aimed at both German- Americans and Russian Jews, and in the immediate aftermath of the war, the attorney general declared that 90 per cent of extreme left activity was ‘traceable to aliens’. The so-called Red Scare that resulted, in which large numbers of leftists were detained and some deported, was short-lived.6 But anti-socialism had achieved a centrality in American politics, and for some this would give new impetus to anti-Semitism.

By then, however, the very danger that socialism seemed to pose had been transformed. In 1917, it achieved power in Russia. Communist parties sprang up across the Western world (and beyond) while in Russia itself a bitter civil war raged between revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries. The counter-revolutionaries lost, but in fleeing to other countries, some of them brought with them a remarkable forgery, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Apparently created by Tsarist police agents in France in the 1890s, the Protocols claimed to be the minutes of a meeting of the international Jewish conspiracy. The spread of Marxism, it claimed, had been deliberately encouraged by Jews. They controlled the press, and thanks to their control of gold, an economic crisis could be created which would throw vast numbers onto the streets. The resulting mobs would attack ‘those whom, in the simplicity of their ignorance, they have envied from their cradles’. Just as with the French Revolution, the people would stumble around, seeking new leaders. Ultimately, in place of the different nation states, a world government would be created, at whose head would be the ‘King-Despot of the blood of Zion, whom we are preparing for the world’.7

To those susceptible to its appeal, the Protocols appeared to explain not only the events of the nineteenth century but the twentieth, and among those it influenced was the leading car manufacturer, Henry Ford. In the early 1920s in a series of articles in his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, the notion of a Jewish conspiracy was used to explain post-war developments. Suggestive popular music, decadent plays, ‘the menace of the Movies’, were all attributable to Jewish influence. American Jewish money had helped to bring about the Russian Revolution, just as Jews were involved in Bolshevik activity inside America. They were central too to the creation of the Federal Reserve, which instead of being government-owned had led to ‘a banking aristocracy’. Many of these articles were brought together in a four-volume collection, The International Jew, and it was in this form that it passed onto later generations of anti-Semites.8

If Henry Ford’s post-war pronouncements were one influence on the later extreme right, the First World War saw another crucial development. The original Ku Klux Klan had been a Southern insurgency against the spectre of black equality, and in 1915 it was revived. Once again, it arose in the South, and racism was central to its re-emergence. The occasion was the Atlanta premiere of an immensely popular early movie, The Birth of a Nation. The film glorified the Klan, portraying members as heroes for killing a black man whose pursuit of a white girl had caused her to leap to her death. Shortly before, the rape and murder of a 14-year-old factory employee, Mary Phagan, had resulted in the lynching of her Jewish employer, Leo Frank, by a masked group, the Knights of Mary Phagan. Some of its members were among the first members of the Klan. In crucial ways, the new group continued in the traditions of its forebear, declaring its belief in Christianity, ‘White Supremacy’ and the ‘Protection of our Pure American Womanhood’. Other elements, however, were new. Shaped by wartime jingoism, it called for opposition to ‘Foreign Labor Agitators’. It was anti-Semitic too. Bolshevism, the Klan declared, was ‘a Jewish-controlled and Jewish-financed movement’, and Jewish international bankers were seeking to dominate the governments of the world.9

The Klan had changed in other ways. The pope, it declared, was an alien despot, and his church hated America and sought to crush it. The Klan was fiercely opposed too to what it saw as a rising tide of immorality. The country, Klansmen claimed, had entered a ‘corrupt and jazz-made age’, and ‘degrading’ films and ‘filthy fiction’ were undermining America. Most strikingly, while the Klan was bitterly hostile to the integrationist demands of such organizations as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, it did find common ground with another black organization. Briefly large numbers of blacks followed the black nationalism of Marcus Garvey and in the early 1920s the Klan’s Imperial Wizard met with Garvey and declared his admiration for a politics that vigorously opposed integration.10

Although emerging during the war, it was not until afterwards that the Klan massively grew, and its growth extended far beyond the South. In Colorado, it has been claimed, one Denver resident in seven was a member, while in its strongest state, Indiana, some 200,000 gathered in 1923 to hear addresses by the Imperial Wizard and the newly inaugurated Grand Dragon. The Klan revived the hooded terrorism that had been so important in the aftermath of the Civil War, but this time the Klan rooted itself in local communities, organizing widely-attended social events, sending deputations to donate money to churches and taking part in election campaigns. It met with opposition, and the organization itself experienced several splits. In Indiana in 1925 the former Grand Dragon (he had led one of the splits) was sentenced to life imprisonment for the death of a white woman state employee he had sexually assaulted. Support for the Klan fell not only in the state, but nationally. Severely diminished, the organization continued into the 1930s. (In 1931, for instance, members in Dallas, Texas, inflicted a whipping upon two communists who were organizing for racial equality. Later in the decade it was similarly violent towards left-wing union activists). 11 By then, however, the Great Depression had hit, and new organizations had emerged.

The collapse of the American economy in 1929 affected both the countryside and the cities. In rural areas, many farmers faced ruin while in the cities, spiralling unemployment devastated the workforce. In 1932, this crisis brought to power the Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His promises of a New Deal were followed by the massive growth of government intervention. Roosevelt was re-elected to office in 1936 and again in 1940. But if the Depression led to a strengthening of the Democratic Party, it led too to an increase in both trade union militancy and support for the Communist Party. All of these would be crucial in the emergence of a new wave of extreme right organizations. Its anti-Semitism would be aimed at the Roosevelt administration and international finance, its anti-socialism at the spectre of a communist seizure of power. Its debt to Populism would be expressed not only through its hostility to bankers but through its championing of embattled farmers. But there was a new element. The Depression was not a solely American phenomenon. It hit Britain, France and other countries, leading to the growth of both communism and the extreme right. In 1933 in Germany, however, it resulted in the victory of national socialism. In the early 1920s, Mussolini’s fascists had come to power and crushed the Italian left. Where this had had little effect on the American extreme right, Hitler’s victory had a more far-reaching effect.

One was the creation of one of the key groups of the period, the Silver Shirts. Writing in 1934, its founder, William Dudley Pelley, recalled his reaction to a newspaper headline announcing Hitler had become the German chancellor. Some years earlier, he had received a psychic message that when a certain German house-painter came to power, then he should bring ‘the work of the Christ Militia into the open’. Now that prophecy had come to pass, he had launched the Silver Shirts to challenge Jewry’s plan to impose ‘satanic protocolism’ on America.12 Having already gained a following in the late 1920s by his claims of special spiritual powers, the transition to political leader did not represent a break with occultism. Pelley linked the Silver Shirts to ‘Biblical . . . Prophecy’, and part of his criticism of the American economy was that a better economic system had already existed in Atlantis. Other of his arguments, however, were less surprising. The Jews, he declared, controlled international banking. They controlled the Federal Reserve, and they had extended their power into other domains. Now, he declared, they controlled the press, the stage, the cinema and the radio. Pelley called for the establishment of a Christian Commonwealth, in which ‘every native-born citizen of proper racial qualifications’ would be entitled to a minimum income. Above that, the government would judge what every individual was contributing to the economy, and what remuneration they should receive.13 In 1936, declaring his intention to ‘disfranchise the Jews by Constitutional amendment’, Pelley ran for president on his own National Christian Party ticket. The result fell far short of his expectations (he only appeared on the ballot in the state of Washington, where he gained less than 1,600 votes).14

If Pelley was an occultist, two other leading extreme rightists of the period came from very different backgrounds. In the late 1920s, Gerald Winrod was a prominent fundamentalist, battling to defend what he saw as Biblical Christianity against theological liberalism, evolution and immorality. This even involved arguing that Mussolini might be the long predicted Anti- Christ, but the coming to power of Roosevelt drew him towards the extreme right. The New Deal was seen as communist, and while Winrod drew on the Protocols, a more significant development was his championing of an older conspiracy theory. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, counterrevolutionaries had claimed that it had really been brought about by a sinister secret society, the Illuminati. This group had been uncovered by the Prussian authorities and reportedly disbanded before the Revolution. But in fact, counter-revolutionaries claimed, it had survived to overthrow the French monarchy. According to Winrod, Marx’s Communist Manifesto embodied ‘both the principles and the spirit of the Illuminati’ and the real conspirators behind Illuminism and the Russian Revolution were Jewish.15

Yet another variant on the extreme right was to be found in the politics of a Catholic priest and radio broadcaster, Charles Coughlin. Initially a supporter of Roosevelt, in late 1934 he announced the formation of the National Union for Social Justice, which called for the abolition of the Federal Reserve, the payment of a living wage to everyone willing to work and a fair profit for farmers. A fervent opponent of international finance, Coughlin subsequently turned against Roosevelt who, he declared, was ‘engaged in keeping America safe for the plutocrats’. In the 1936 presidential election, as we have seen, Pelley ran against Roosevelt. Coughlin, however, supported a different candidate.16

The Depression had brought a variety of movements into existence. One was the Share Our Wealth Society, which called for limits on wealth so that every family could be paid an annual income. Others supported the Townsend Recovery Plan, which argued that the payment of a monthly pension to senior citizens could bring about the injection of increased purchasing power into the economy. In 1936, Townsend and the former national organizer of the Share Our Wealth Society, Gerald L. K. Smith, joined with Coughlin to create the Union Party. As its presidential candidate it selected Republican congressman William Lemke, who had already sought to introduce legislation to protect farmers from the loss of their farms. Unless Roosevelt stopped flirting with communism, Coughlin announced, ‘the red flag of communism will be raised in this country by 1940’. Despite the following Coughlin and the other components of the Union Party had built up, however, it gained less than 2 per cent of the vote.17

In 1938, Coughlin launched yet another organization, the Christian Front. Greedy capitalism, it claimed, was pushing ‘mistreated workers’ tow...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Before Brown

- 2 American Reich

- 3 Out of the Southland

- 4 Not all Patriots

- 5 Race and religion

- 6 Fighting for women

- 7 A call to arms

- 8 Race and the right

- 9 Out of the 1950s

- Notes

- Bibliography