![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

TECHNICAL STUDY

Part 1

Introduction

1 The warehouse as part of the distribution system

2 The project team

An introduction to the problems of designing storage buildings, and the role of the project team.

1 The warehouse as part of the distribution system

1.01 Industrial stores are not usually designed to earn profits. Costs incurred are reflected in the production or distribution accounts, and are ultimately passed on to the consumer. Thus as the design of a warehouse affects handling and storage costs, which help to fix commodity prices, the architect or designer bears considerable responsibility to the public. For this reason, a warehouse should be considered as part of the total supply chain and distribution system from the outset. In many warehouses the operator has asked a consultant to develop a brief orientated towards mechanical handling at the expense of the efficiency of the distribution system; several of these are virtually redundant after only a few years’ service (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 In many warehouses the operator has asked a consultant to develop a brief oriented towards mechanical handling at the expense of the distribution system.

1.02 It is therefore in the client’s interest that multidisciplinary expertise should be used in a total system approach; architects, with their inherent knowledge of planning in three dimensions, paired with expert supply chain and materials handling consultants are best placed to evaluate and select storage systems matched to the buildings surrounding them. Consultants should be retained from the outset to examine the economics and flow patterns of the supply chain and distribution system. This responds to the user’s manufacturing and marketing potential, working in parallel with, and contributing to, the architect’s investigation into the best storage arrangement and building type for the required through-puts: it also considers, in relation to the product’s packaging, the potential for mechanical handling and the effects of future change.

Warehouse design

1.03 There are no hard and fast rules for warehouse design; policy decisions depend on type of product, the speed that it will pass through the warehouse, the type of outlet and consumer market being served and the distance of travel involved. For example, there are conflicting opinions about whether storage facilities should be centralized. Two very large household names in the retail trade, one in pharmaceuticals, the other in groceries, have similar outlet patterns but employ different distribution systems. One has a central factory and uses several redistribution centres around the country, operated by contractors. The other employs 13 main bulk storage warehouses, all but three operated by third party contractors, with all ‘own label’ manufacture and processing outsourced: advanced point of sale-driven computer reordering drives mechanized replenishment and automated sorting for delivery to individual retail outlets.

1.04 Although this decision is usually based on supply chain operations and market research, and is the client’s responsibility, the pattern can be seriously affected by other factors. The form and unit size in which the product reaches the store is a prime consideration. This will increasingly be influenced by issues such as ‘sustainability’, environmental and energy issues, production cost and marketing considerations, without sufficient regard for the storage medium. By understanding the product and its handling properties, design teams can feed back useful data to the client, resulting in a more efficient package, a reduced cost of packaging materials and higher efficiency of storage and handling systems.

1.05 Good examples of this approach are companies which add value to suppliers’ contracts and impose detailed packaging specifications, including size, shape and materials, and supply the handling crates: this has enabled them to cut warehousing and handling costs considerably. It is possible to take a supplier to court for breach of contract for unacceptable packaging. Specifications for Internet auctions for major supply contracts include detailed logistics information of this type.

1.06 Equally, transport should be considered as a flexible system, integrated with the warehouse by employing dimensionally co-ordinated unit loads. Even some newly built installations which are considered well planned have cramped loading bays which choke in peak conditions (the company forgot that suppliers’ vehicles were larger than their own, and only provided very constricted manoeuvring space). In the handbook, data have been included on vehicle types and sizes to aid designers planning for transport.

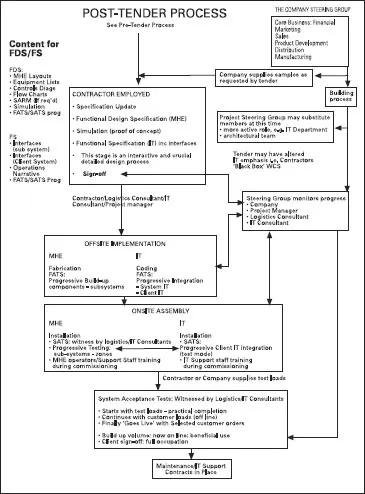

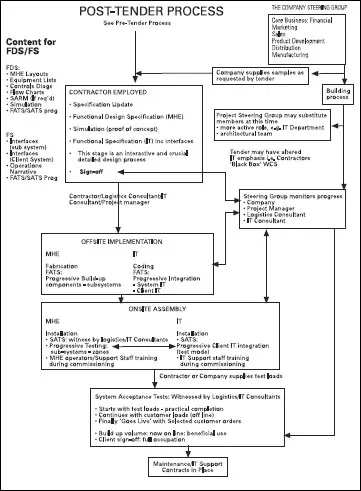

1.07 The architect’s opportunity in this very competitive field should therefore be the co-ordination of these systems, keeping an overall view of the project and its part in the total manufacturing and distribution system. Figure 1.2a/b sets out a typical project sequence for a state of the art retail distribution warehouse including a product sorter, divided into two principal stages: before and after the appointment of the implementation contractor. There are many ways of organizing major capital projects, such as design and build and construction management, the selection of which are outside the scope of this publication. These diagrams illustrate a typical process sequence with the parties, controls and approvals involved at each stage.

2 The project team

2.01 The design of such a complex building as a warehouse, combining building fabric and sophisticated plant, can only be carried out by a team. Many equipment manufacturers offer package deals, especially for complicated installations such as automated high-bay warehouses. Though very knowledgeable in equipment, they are not concerned with other factors outside this sphere. Professional involvement is therefore vital to protect the client. Each specialist member of the team must keep the others constantly aware of the effect which various decisions will have on the project.

Members of the team

2.02 There is no single form for a project team, but the skeleton team outlined here is a useful guide. Size and complexity of a project will obviously govern the content. The part that each member of the team plays in the development of different zones will be discussed more fully in specialist sections of the handbook. The project team should include:

Basic members

Multidisciplinary leader (opportunity for architects)

Representative from client’s management:1 the project ‘champion’

Structural engineer

Quantity surveyor/cost consultant

Mechanical services engineer

Electrical engineer

Public health engineer

Accountant/business consultant1

Supply chain consultant

Mechanical handling consultant

Mechanical handling engineer

Representative of the insurance company involved.

These naturally group into say six specialist multidisciplined consultants

Team members passing through at various stages

Distribution manager1

Existing warehouse manager(s)

Future warehouse manager1

Transport manager1

Works Council including union shop stewards1

Warehouseman/operatives/drivers selected from the floor1 (Figure 1.3).

Local authority representatives, i.e. building inspector, factory inspector, fire officer, etc.

Figure 1.2a The pre-tender process.

Figure 1.2b The post-tender process.

2.03 No project team, however well organized, can o...