![]()

1.

INTRODUCTION

One is apt to think that a culture is more attached to its values than to its forms, that these can be easily modifed, abandoned, taken up again; that only meaning is deeply rooted. This is to… ignore the fact that most people cling to ways of seeing, saying, doing and thinking more than to what is seen, to what is thought, said or done…

A whole history of the formal in the twentieth century remains to be done: attempting to measure it as a power of transformation, drawing it out as a force for innovation and locus of thought, beyond the images or the “formalism” behind which some people try to hide from it.

–Michel Foucault

PROLOGUE: INFERNAL RETURNS

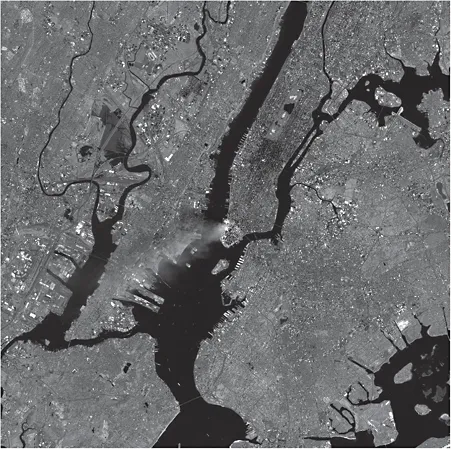

On a late summer morning at the dawn of a new millennium, the identity between architecture and the body returned with a sound like thunder. And then it was doubled. The trauma of the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center was so effective in part because it evoked the relationship between architecture and our sense of embodiment. Just the day before, such an identity between buildings and bodies seemed a quaint myth in our age of transnational dot-com capital. Yet, between the impacts and the Towers’ smoky absence, an intimate psychical identification seems to have been made across the buildings and those who watched from a safe distance or via telepresence. In the following days, the Towers’ destruction was represented as a wound, a personal one for many, but also as a symbolic injury to the collective political body of the nation and even to the nebulous body of culture dubbed “civilization.”

The World Trade Center was a complex object for such projections. On the one hand, the Towers were proportioned like colossal Doric columns, long celebrated as recalling the standing body. The points of impact appeared like gashes in the taut steel and glass skin; the doubling of the event stretched the instant of shock into a televised duration replayed repeatedly. On the other hand, the edifice was exactly the sort of modernist architecture often criticized as dehumanizing and scaleless. Indeed, before the attack, Minoru Yamasaki’s towers served as icons not for the body but for modern architecture’s inhuman abstraction. Their vast size and generic blankness seemed symbolic of globalization’s incompatibility with humanism and humanistic environments. Upon the building’s completion, Lewis Mumford criticized the complex as an example of technocratic megalomania. Not only did the design not reflect the human body, it embodied the forces of unchecked modernity that, Mumford decried, were “eviscerating the living tissue of every great city.”1 The Towers were, in short, seen themselves as weapons and invaders attacking the body of the city and the cosmopolitan body politic born from the womb of the metropolis.

Of course, such identifications only tentatively rely on the forms of the object. Indeed, the identification formed on September 11th seemed to have been not a symbolic identification with a thing so much a desire for such at the very moments of its impossibility. Slavoj Žižek has suggested that part of the shock of the event lay in familiar phantasmagoric Hollywood images of destruction being suddenly rendered really Real. The Towers, Žižek suggests, were peculiar symbols of the disembodied hyper reality of global finance.2 Perhaps in a similar way, the physiognomy of the Towers foreshadowed the day’s unrepresentable events. Their abstract physique did not signal simply a lack of a body-building identification but rather shrouded the void that underlay all such metaphorical constructions. In their twinned blankness, they stood like vast brackets in an urban field, at once holding open and cloaking the dissolution of architecture’s capacity to articulate subjects’ relationship to a collective Reality.3 This gap was revealed as the buildings’ apparent monolithic stability was replaced by punctures that transformed the buildings’ bulk into seemingly paper-thin lace curtains. Indeed, their steel lattice and truss structure, as it turns out, was integral to the way they withstood the initial impact and the dynamics of their collapse roughly an hour later. The void that was bracketed became apparent in those minutes. The symbolic relation of architecture to our body or sense of embodiment was not something remembered so much as experienced as already lost. No wonder images of the Towers in television shows and movies were digitally removed so quickly afterwards.

This is also evidenced by the popular reaction against the initial proposals for rebuilding the site as yet another generic global simulacra. There was a moment when architecture’s role in articulating collective desire seemed to matter again. Donald Trump’s counter-proposal to construct a precise imitation of the World Trade Center Towers–but fortified–was impossible for the same but inverted reason in that it would have created a double bracket, converting the events into simulations. Or, think of the popularity of Daniel Libeskind’s “Memory Foundation” master plan. His original proposal for One World Trade Center consisted of a 1776-foot angular shard with an offset spire that aped the physiognomy of the Statue of Liberty. The other buildings were to have mirrored this first building as progressively smaller fragments. In this all-too-literal proposal, the two lost towers were to have been reconstituted as an echo of an architectural colossus, a body sown together out of pieces, a kitsch Frankenstein monster, not a monument for the victims so much as the simulacral monumentalization of America’s bewilderment within the “desert of the Real” suddenly made apparent in lower Manhattan.

As I watched that day’s events from London, a few lines from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness reverberated with the images on my television screen:

I had first encountered this passage through Anthony Vidler’s book The Architectural Uncanny, and (on a day that had begun for me like any other around that time, with research for what would become this book) I could not help but feel an uneasy sense of repetition.5 Sartre was speaking, of course, about World War II and the age of intercontinental nuclear warfare and not of the different geo-strategic space of the twenty-first century. Nevertheless, once again, our “manageable instruments”–from the planes to the television media, to the cell phone that first brought the news to me within the British Library, to the internet and even information infrastructures used by the terrorists and global capital alike–were converted into weapons against the metaphorical body of the World Trade Center, which also served as a synecdoche for an entire nation and as a metonymy for global capital. Once again, architecture participated in disassembling symbolic structures.

Moreover, this dynamic of disassembly seems to have been mobilized in reverse in the subsequent “war on terror.” The attacks on the crystalline geometries in New York (and revealingly, far less the lumpen Pentagon) are portrayed as attacks on the edifice of “western civilization.” Meanwhile, the outsiders are presented as nomads hiding in the caves of Tora Bora or in holes under the Iraqi desert. Reversing Aristotle’s claim that the construction of cities is a crucial demarcation of culture, this representation of a lack of architecture becomes one mechanism to convert their representation as human subjects into less-than-human “enemies,” or even as, “collateral damage,” that is roughly equivalent to buildings. Likewise, holding detainees in cages at Guantánamo Bay, a placeless spot removed from any nation’s domestic space, is one small way of repeating the Bush administration’s rhetoric that such “illegal combatants” are not members of any body politic and therefore not protected by either social contracts (constitutional protection and international treatise) or human rights. Bentham’s Panopticon may have been architecture for disciplining the criminal subject (as Foucault argued) through an apparatus of vision, but the prisoners of Guantánamo are presented as undeserving of legal representation via architectural orthopedic correction. To echo Judith Butler’s arguments in Precarious Life, withholding architecture from these other bodies helps to absolve our complicity with the violence done to these persons, guilty, innocent or in the wrong place at the wrong time.6 This dynamic is also at work domestically since the attacks on the World Trade Center provided the mechanism for advancing what Giorgio Agamben has called a “state of exception” that suspends legal structures of the collective body politic in favor of control over the “bare life” of individual bodies.7 What bodies are being adapted through these tools of power, what subjects are we fashioning through these “manageable instruments”?

THE BODY OF ARCHITECTURAL KNOWLEDGE

This book is not about those events, but its time frame is bracketed by the war chronicled by Sartre and the hyper-Orwellian “war on terror” inaugurated in 2001. This book is about the relationship between architectural form, the body, subjectivity and epistemology in the last half-century of architectural theory and design. Or rather, I examine the role of that which architects call “the body” in articulating the relationship between architectural form and

architectural ideas of subjectivity. I am, therefore, also concerned with the spaces and dynamics of projection through which objects of knowledge and concepts are formulated. I hope that this theoretical examination operates as a partial history of the present, a moment when the very concepts of the body, order and subjectivity all promise to be radically transformed by digital technology, new organizations of power, and when the traditional objects and ordering of architectural knowledge seem in crisis or even eclipsed.

My primary site of examination is the sudden, and heretofore unexplained, re-appearance of the human figure in mid-twentieth-century architecture and its relationship to recent interest in the body in reference to issues of post-humanism, digital technology, globalization and science. There are several reasons why I locate my inquiries around this apparent backwater of modern architectural history. First, histories of modern architecture have overlooked the discourse around the human figure prevalent between the late 1940s and the early 1960s in many parts of Europe and America. A few articles exist, but these are often very specific or idiosyncratic; still others, which often seek to continue this discourse, are theoretically regressive. Accounts in broader historical texts are absent or cursory. Even Le Corbusier’s Modulor, the most famous representative of this discourse, has received relatively little attention in accounts of his œuvre. Yet, even today, many books are published each year claiming some correspondence between design, the human body, natural forms and geometric proportioning system such as the Golden Section and Fibonacci series.8 Secondly, there has been a renewed interest among progressive architects in early-twentieth-century arguments for the geometric ordering of natural bodies, such as found in D’Arcy Thomson’s On Growth and Form. To understand what might be at stake in such arguments, it seems useful to examine a historical discourse that referred to similar or even the same referents as a way of ordering architecture. Fourth, architectural discussions of the body, humanism and post-humanism frequently refer to the mid-century discourses on proportion, but rarely in detail or as a straw-man. This book, in contrast, attempts to map a partial preconscious topology of contemporary architectural thought, seeing the modern discourses of proportion not as a backwater but as a hinge to current issues.

Lastly, while the mid-century interest in the body is usually presented as a return to...