- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture, Technology and Process

About this book

This new selection of essays follows Chris Abel's previous best selling collection, Architecture and Identity. Drawing upon a wide range of knowledge and disciplines, the author argues that, underlying technological changes in the process of architectural production are fundamental changes in the way we think about machines and the world we live in.

Key topics include: new patterns of urbanism in the fast growing cities of asia pacific; metaphorical extensions of mind and body in cyberspace; the divergent European and North American values shaping Sir Norman Foster's and Frank Gehry's work, and the collaborative work methods and technologies creating the adaptable design pratices of today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General| 1 | ARCHITECTURE IN THE |

CHANGING SCENARIOS

Given the 1997 financial crisis and its aftermath, it is sometimes hard to believe the heady optimism of the preceding years which heralded in what came to be known as the Pacific Age, or the coming Pacific Century. Such optimism was not unfounded, however, and, severe as these problems still are in some places, it is my personal belief as well as that of many other observers that they will eventually pass, possibly sooner rather than later, and that the region will yet fulfil its promise. It is worth reminding ourselves, therefore, what the original excitement was all about.1

Among the first to recognize the new order was the macro-historian Johan Galtung.2 Speaking at a 1981 seminar in Penang, Malaysia, on regional development, Galtung painted a convincing picture of the relative decline of the West against the then rising economic power of Japan and the emergent ‘tiger economies’ of Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore (Fig. 1.1). The following year, at a meeting at the East West Centre in Honolulu, Hawaii, Zenko Suzuki confidently announced:

… the birth of a new civilization which nurtures ideas and creativity precisely because it is so rich in diversity. This is the beginning of the Pacific Age, an age which will open the doors of the 21st century.3

(Macintyre, 1985, p. 11)

In the same year, the British Broadcasting Company lent its own weight to the same thesis, and, looking ahead to the coming century, named it with Mary Goldring's 1982 radio series, The People of the Pacific Century. A BBC television series and book titled The New Pacific4 followed 3 years later.

Also in 1985, William Thompson published his own related book Pacific Shift.5 In it, he charted the sequential evolution of four great civilizations: Riverine (meaning the early Middle Eastern civilization founded between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers); Mediterranean; Atlantic; and Pacific, each identified by a specific technological as well as geographical origin. Thompson argued that the fourth emergent civilization marks a fundamental change, not only of the main direction of North America's trade – from Europe to Asia Pacific – but also of the technological foundations of that trade, from maritime communications to air travel and electronic communications, changing with it the whole basis for cultural exchange.

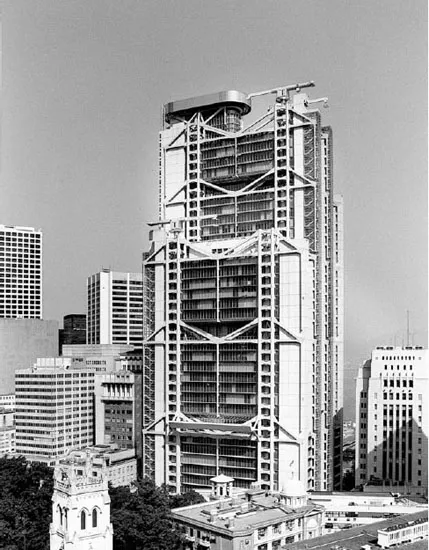

By that time too, the era had also acquired its first built symbol in Norman Foster's innovative Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (Fig. 1.2). Writing on its completion in 1986, I described it as ‘a building for the Pacific Century’.6 It was the very first building of any kind to earn that description. Appropriately sited in the burgeoning city that most clearly defined the meaning of a tiger economy, the Bank encapsulated the confident, forward looking spirit of the times, and still challenges the region's architects and leaders to live up to those aspirations.

The following years brought a steady stream of eulogies on the ‘Asian Miracle’, and its special combination of state patronage and private enterprise. Significantly, in 1996 the UK's then Leader of the Opposition, now Prime Minister Tony Blair, chose Singapore as the preferred site for announcing his own newly forged and related economic policies. It seemed that, after decades if not centuries of hearing that West is best, the East was finally realizing its historical potential – at least in terms that the West could appreciate.

Recent events, fueled by problems in the Japanese economy and culminating in the continuing financial difficulties in parts of Southeast Asia, have served to qualify the heady scenario of untrammelled growth and optimism, leading many observers to wonder whether the Asian Miracle might already be at an end.7 The xenophobic glee with which some Western commentators jumped to this conclusion probably says more about the fragility of Western egos than it does about the fragility of Asian economies. More cautious observers, pointing to the high levels of savings, investment and education in the region, argue that the same enduring factors will ensure future rapid growth, if not at the same rates as before, then at still impressive rates by Western standards. Current problems, they say, arise from questionable investments encouraged by lax lending policies, policies which can and are being changed.8

These more positive assessments are borne out by long-term demographic analyses which suggest that, with the notable exception of ageing Japan, the favourable balance throughout Asia Pacific of young and productive to older and non-productive populations will continue to guarantee expanding economies well into the new century.9 Not least, there is the overwhelming role of China, whose economy continues to grow at a phenomenal rate and is predicted to overtake the US to become the largest in the world in less than two decades.10

If for no other reason, the increasingly vital and turbulent relations between these two giants will ensure the century continues to be called after the ocean which both separates and joins them together.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES

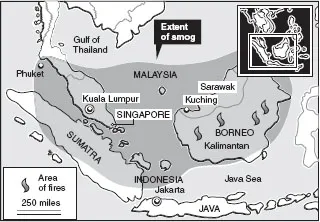

It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that the long-term economic prospects for the region remain buoyant. Far more worrying are the present and future environmental consequences of the same impressive economic performance. And here we have to wonder just what we mean by ‘success’ in conventional economic and development terms. Recently, much of Southeast Asia has lain shrouded in a dense cloud of life-threatening smog, the product of a lethal mixture of forest fires and urban pollution (Fig. 1.3). The fires, which were deliberately started by logging and plantation companies as part of their normal ‘slash and burn’ practices,11 were mainly located in Indonesian Sumatra and Borneo and spread over a total area of 600 000 hectares, or 1.5 million acres – an area roughly equivalent to the entire Malaysian Peninsula. Aside from the ecological disaster, the after-effects of smoke from the fires, coupled in cities like Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta with already high levels of airborne traffic pollution, is likely to affect human health and economic patterns in the region for years to come.12

Extraordinary as the scale of the disaster is, it was easily predicted. From 1982 to 1983, similar fires in Indonesia consumed over 3.5 million hectares of forest in the state of Kalimantan.13 Some years ago on a visit to Kuala Lumpur I witnessed the disastrous effect of further Indonesian fires on that city's air quality. Then as now, the fires were the direct result of the same short-sighted industrial and agricultural practices. Then as now, although the corporations concerned – usually joint ventures between Indonesian and other Southeast Asian companies – were reprimanded, no serious actions were taken against them.14

Environmental disasters are not of course unique to Asia Pacific and it is understandable if Asian leaders, as they have done, should accuse Western leaders and environmentalists of hypocrisy when they come under criticism for such events – especially when such criticism emanates from countries which import the products of the same devastated forests.15 It is understandable perhaps to react in this way, but it is not a sufficient reason for not taking action to prevent events which clearly have such self-destructive consequences.

Paradoxically, the root cause of this and similar environmental disasters is more likely to be found in the cosy alliance between state patronage and private interests which typifies business patterns in Asia Pacific and ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Architecture Technology and Process

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Architecture in the Pacific Century

- 2 Cyberspace in mind

- 3 Technology and process

- 4 Foster and Gehry: one technology; two cultures

- 5 Harry Seidler and the Great Australian Dream

- 6 Mediterranean mix and match

- Appendix I: Biotech Architecture: a manifesto

- Appendix II: Birth of a cybernetic factory

- Notes and Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architecture, Technology and Process by Chris Abel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.