This is a test

- 116 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is about children with dyspraxia: developmental co-ordination disorders (DCD) and what teachers and other professionals can do to promote their learning and their social inclusion in a mainstream setting. The author addresses issues which affect access to the curriculum in Key Stages 1-4 and offers strategies to support children which have proved effective to experienced practitioners and can be managed in a group or class context. A key component of the book is an understanding of the emotional and social needs of children with dyspraxia.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Inclusion for Children with Dyspraxia by kate Ripley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

An Introduction to Praxis

Children who are identified as having difficulties with movement control are increasingly recognised as children with special educational needs. Some of these children will be at the extreme end of the normal distribution for motor skills: opposite to that of a Michael Owen/Denise Lewis and any of our other sporting icons. Others may have diagnosed medical conditions such as lax ligaments, low muscle tone or dyspraxia. Changes in attitude and understanding during the past decade have resulted in a new awareness of the effects that motor impairment may have on learning, self-esteem and social/emotional development.

These guidelines have been compiled to help teachers to understand more about the difficulties that children with motor-skill problems experience in school. The guidelines address the social implications as well as the associated learning difficulties and include some strategies to support children through the key stages.

Praxis

‘Praxis’ is a Greek word which is used to describe the learned ability to plan and to carry out sequences of coordinated movements in order to achieve an objective. ‘Dys’ is the Greek prefix ‘bad’ so dyspraxia literally means bad Praxis.

A child with difficulties in learning skills such as eating with a spoon, speaking clearly, doing up buttons, riding on a bike or handwriting may be described as dyspraxic. The movements which are involved in these activities are all skilled movements which are learned and voluntary, i.e. under the conscious control of the individual who carries them out.

Developmental Dyspraxia is found in children who have no significant difficulties when assessed using standard neurological examinations but who show signs of an impaired performance of skilled movements. Developmental Dyspraxia refers to difficulties which are associated with the development of coordination and the organisation of movement.

Praxis is learned behaviour but it also has a biological component. The sequence of motor development is predetermined by innate biological factors that occur across all social, cultural, ethnic and racial boundaries (Gallahue 1992), but the learning of motor skills can only progress in the context of continued interaction with the external environment. The early learning of movement skills usually takes place in the context of play.

Alternative terminology

The term ‘Developmental Dyspraxia’ has been selected as the title for the guidelines because dyspraxia has implications for the processing of sensory information as well as for the planning and execution of skilled voluntary movements. There are, however, four terms in common use to describe motor problems, particularly in the USA and Canada and these may appear in the reports from other professionals.

In 1994 the term ‘Development Coordination Disorder’ (DCD) appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV). The characteristics were described as:

- problems with movement and spatial-temporal organisation;

- qualitative differences in movements from peers;

- the presence of co-morbid features which affected a wide range of functioning.

Like Developmental Dyspraxia, the condition was seen as being a chronic, usually permanent, condition in which the impaired motor performance could not be explained by the age or the ability of the child in question. Polatajko et al. (1995) have described DCD as a problem with the execution of motor movements and it is often used synonymously with the term ‘Clumsy Child Syndrome’.

For Sugden and Keogh (1990) a diagnosis of Developmental Dyspraxia should include, as a key feature, problems with the planning or conceptualising of motor acts.

The final term ‘Sensory Integrative Dysfunction’ places the emphasis on the ability to receive and to process information from the senses with accuracy.

There is, as yet, no common agreement about the groups of children (the population) that each of these terms describe (Polatajko et al. 1995). The term ‘Developmental Dyspraxia’ has been the one used in these guidelines because it includes reference to all the three elements which are needed for efficient Praxis.

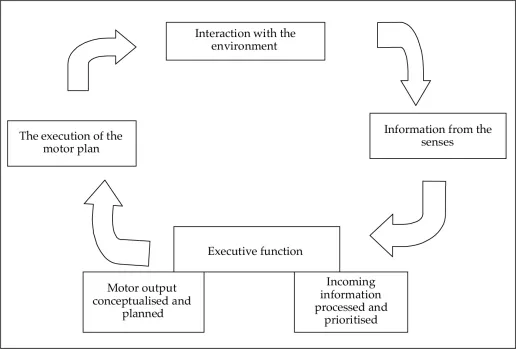

Three elements, as described in the following sections, are needed for efficient Praxis and the term ‘Developmental Dyspraxia’ best relates to all three of these components. They are represented in Figure 1.1.

1. Sensory input and processing

Terms such as ‘Sensory Integrative Dysfunction’ emphasise the receiving of accurate information from the senses, particularly vision, tactile receptors, the vestibular apparatus and the proprioceptive system. The hearing, smell and taste receptors may be relatively less important in the context of Praxis as a child gets older.

Five senses (vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch) are familiar to all, but the vestibular and proprioceptive systems may require some further explanation.

Figure 1.1 The components of efficient Praxis

The vestibular system

The vestibular receptors are found in the inner ear. The vestibular sense responds to body movement in space and changes in head position. It automatically coordinates the movements of eyes, head and body, is important in maintaining muscle control, coordinating the movements of the two sides of the body and maintaining an upright position relative to gravity.

The information from the vestibular apparatus is projected to the cerebellar area of the brain, which is associated with a range of functions.

Function | Possible difficulties |

1. Learning new movements | Learning new skilled movements will be slower than for most children. |

2. Memory for movement patterns | The movements that we learn slowly and then become automatic, like walking, driving, handwriting, may never achieve the degree of automaticity and, therefore, efficiency that other people achieve. Children may always have to think about the mechanics of handwriting, and use letter and word. Most adults can shut their eyes and write their name efficiently because the motor plan is well established. |

3. Fluency of movements | Movements such as running or the transition between different movements may appear clumsy and dysfluent because the timing is faulty. |

4. Sequencing of movements | Complex actions usually involve a whole sequence of movements which need to be assembled in the correct order, e.g. when performing a dance routine or changing gear ina car. Some people find sequences of movement very hard to achieve. |

5. Control of posture | Children who find it hard to maintain a steady balance and posture may:

|

The proprioceptive system

The proprioceptors are present in the muscles and joints of the body and give us an awareness of our body position. They enable us to guide arm or leg movements without having to monitor every action visually. Thus, proprioception enables us to do familiar actions such as fastening buttons without looking. When proprioception is working efficiently, adjustments are made continually to maintain posture and balance and to adjust to the environment, for example when walking over uneven ground.

The proprioceptive system helps us to develop a body image by giving information about where different parts of our body are positioned relative to the environment. Without a clear image of our own body boundaries, it is hard to develop a spatial awareness of our surroundings.

Children who have difficulties with proprioception may:

- find it hard to know where on their bodies they have been touched unless they have observed the movement;

- find it hard to identify objects that they could recognise visually in a ‘feely bag’ (or for adults, to get out the mobile telephone quickly from a large handbag)

- find it hard to build up the mini-motor plans which we rely on for fastening shoelaces, buttons, while our attention is engaged elsewhere;

- fall frequently in situations such as walking over rough ground or moving from one surface to another;

- show small adjustment movements, particularly of the limbs, in an unconscious attempt to stimulate the proprioceptors in order to get feedback about where parts of their body are in space. This, linked with other postural adjustments because of postural control difficulties, may increase the possibility of an inappropriate AD/HD diagnosis unless a full multidisciplinary assessment is carried out.

The information which has been received from all seven senses has to be interpreted by the brain. The ability to integrate the information from the senses is known as sensory integration. Occupational therapists will often start their treatment of a dyspraxic child by working on sensory input and sensory integration.

2. Motor planning

The second component of Praxis is the ability to plan a coordinated response which may involve movements and movement sequences which have a range of complexity. Children who have difficulties with this planning component have been identified as having Ideational Dyspraxia.

The term describes difficulties with the planning of a sequence of coordinated movements or with actions which involve the manipulation of objects. The individual actions may be carried out competently, e.g. hammering a wooden peg, but the order of the actions may be lost, e.g. failing to put the peg in the hole before hammering. In older children, organising tasks, equipment and their ideas may become a problem.

3. The execution of the motor plan

The third component of efficient Praxis is the execution of the motor plan. Difficulties in this area have been described as Ideo-motor Dyspraxia, and the terms ‘DCD’ or ‘Clumsy Child Syndrome’ emphasise this component of Dyspraxia. Children with Ideo-motor Dyspraxia know what they want to do, but find it hard to execute their action plan. The performance of individual actions may be clumsy, slow, awkward, non-fluent and children may experience particular problems with transition: moving from one action to the next. Everyone has experiences of failing to meet their own expectations about executing a motor plan, whether it is a poor putt or dropping the casserole dish. However, most of us manage a ‘good enough’ performance most of the time.

The development of Praxis

The development of Praxis is a complex process which involves changes in the neural networks in the brain (learning) so that information from the senses ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. An Introduction to Praxis

- 2. The Assessment of Dyspraxia: A Team Approach

- 3. The Role of the Teacher in the Assessment of Developmental Dyspraxia

- 4. The Social and Emotional Implications of Dyspraxia

- 5. Key Issues for Key Stages 1 and 2

- 6. Key Issues for Key Stages 3 and 4

- 7. Case Study Examples of Interventions through Key Stages 1–4

- 8. Activities to Develop Motor Skills and Self-esteem

- Appendix I: Motor Development

- Appendix II: Overview of the Developmental Stages for Achieving Pencil Control

- Appendix III: Handwriting Norms

- Appendix IV: Motor Skills Checklist used for the Esteem Clubs

- Appendix V: Observation Checklists for Motor Skills

- References

- Index