- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text explores a range of strategies, both institutional and individual, which have been developed by academic and support staff, to foster the kind of atmosphere, facilities and attitudes in relation to learning which support systems.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

BildungSubtopic

Bildung AllgemeinStrategies and Support for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Teaching and Learning

Chapter 8

Can You Teach an Old Dog New Tricks?

Student Induction on an HND Extension Degree

Introduction to the Problem

In common with many other of the new universities, Manchester Metropolitan (MMU) offers students the chance to build upon their Higher National Diploma (HND) qualification and read for a degree. Within the Department of Business and Management Studies at Crewe and Alsager Faculty, there are three linked degrees offering two-year extension programmes. The degrees have the standard MMU Credit Accumulation and Transfer (CATs) structure and are made up of six modules per year. Of these modules, three are common in each year, with the remainder being specific to the degree route. The common modules are taught as mass lectures with smaller tutorial follow-up groups. The routes are BA (Hons) Business, Sport and Recreation, BA (Hons) Business, Leisure and Recreation and the BA (Hons) Business Administration, colloquially known as BABSR, BABLR and BABA. These three degrees recruit approximately 100 students from an internal market of around 300 HND students, plus students from other institutions.

The ‘three degrees’ course team perceived that there was a very different culture in degree work compared to diploma work and so a problem of change would be faced by the ex-HND students. This view was supported by the very first cohort of Business, Sport and Recreation degree students who reported the need for some form of induction programme. This degree recruited its first cohort in 1992/93 while the other two degrees recruited their first cohorts in 1993/94.

The underlying rationale for the induction programme was to encourage students to adopt a more meaning-oriented approach to studying. Staff involved in the programme wished to make the issue of differences in approach between HND studies and degree studies explicit and hence influence students’ habits.

Differences Between Degree and Hnd

As a starting point for planning the induction programme, the course team informally sought the views of colleagues who taught both on diploma and degree routes. Most colleagues reported that the HND is more vocationally oriented than the degree route. However, when pressed, colleagues were unable to point to specific and quantifiable differences between the routes. In an attempt to classify the differences, the structure for analysis of curriculum styles and strategies proposed by Heathcote et al. (1988) was used. The structure proposes four headings:

• Curriculum intentions

• Organization of the curriculum content

• Instructional procedures

• Assessment and grading.

Curriculum intentions

Under this heading it was found that there was little difference between the routes. It is likely that the current pressure to adopt a standard university style for course definitions will lead to even smaller differences in the future.

Organization of the curriculum content

In the early days of the Business Education Council (BEC) and Technical Education Council (TEC) awards there was considerable pressure to move away from traditional ‘subjects’ and integrate curriculum content under a series of key themes. Typical of the pressure was the development of the composite topic ‘Business Environment’. The curricula for the degrees and the HND showed no significant differences in this area. The degrees contained a number of composite modules and similarly the HND contains a number of traditional subject modules.

Instructional procedures

Heathcote et al. (op.cit.) divide this heading into four categories, of which three are appropriate to this discussion:

– The Exposition-Discovery Learning Dimension. Colleagues reported very little difference in the way that the acquisition of curriculum material was achieved on both the degrees and the HND. A common complaint was that pressure of numbers was forcing delivery into the mass lecture mode against the tutors’ wishes.

The Exposition-Discovery Learning Dimension. Colleagues reported very little difference in the way that the acquisition of curriculum material was achieved on both the degrees and the HND. A common complaint was that pressure of numbers was forcing delivery into the mass lecture mode against the tutors’ wishes.

The Expenential-Non-expenential Dimension. It was at this point that the first significant difference emerged. Again tutors provided students with both experiential and non-experiential learning situations. On both routes, the preference of tutors appears to be for experiential learning but there appears to be a difference in emphasis. There is an expectation for degree students that they will bring to any problem a broad background of theoretical knowledge derived from reading round the topic. In the case of HND students, it is usual to expect students to adopt a pragmatic approach to problem-solving in line with the Business and Technical Education Council (BTEC) Common Skills philosophy. The theoretical structures used are normally based upon those identified by the tutors in class and specified reading.

– Teacher Control-Student Control of the Learning Outcome. A further difference is that the degrees place great emphasis on assessments being open-ended so that every student can arrive at their own unique solution. This also occurs on the HND, but there are more occasions when the learning outcome is highly teacher-specified.

Assessment and grading

Under this heading, some more differences emerged. The HND uses both course work and examinations while the degrees are continuously assessed except for the language modules. However, this difference is peculiar to the three degrees within the department. Most other degrees in the faculty include examinations for grading purposes.

The assessment of the curriculum differences, while identifying some possible problem areas, was rather less clear cut than had been expected. The much quoted Vocational orientation’ of HND was not identifiable using the chosen tool.

The only other major difference appeared to be in the initial entry qualifications for the HND compared to three-year degree routes elsewhere in the faculty.

The HND requires one A level or equivalent while two A levels or equivalent is needed for a three-year degree. However, even this distinction was complicated by the small number of students entering HND with two A levels or good Ordinary National Diploma (OND) grades. Anecdotal evidence from colleagues also suggested that there is little difference between the ‘average’ HND student and the ‘average’ degree student. A large part of any difference seems to depend upon the individual student’s motivation and interest in the subject.

The issue of motivation and effort has also been mentioned by the HND students themselves. They often confess to having lacked commitment and effort in their studying at school, and blamed this on their ‘poor’ A level results. Since the induction programme was for ex-HND students entering an extension degree route, it was felt that this issue of students’ commitment and approaches to study might be worth considering.

The extensive literature on the topic (eg, Entwistle and Ramsden, 1983; Richardson, 1990; Gibbs, 1992) suggests that students are likely to adopt one of two, or possibly three, approaches to studying. The meaning approach, in which the student has the intention to understand and internalize the material, is considered to be the most appropriate and desirable for undergraduates (Gow and Kember, 1990). The reproducing approach, where the student has the intention to get by with as little understanding as possible, is considered to be undesirable. A third possibility, the strategic approach, is postulated by Entwistle (op. cit.), but disputed by Richardson (op. cit.). Whether the adoption of a meaning approach is beneficial to the student’s grading performance is still a matter of debate and will probably depend upon the form of assessment used. Ely (1992) found that a meaning approach was beneficial, while Beckwith (1991) took the opposite view.

As part of a different investigation, the Richardson version of Entwistle’s Approaches to Study Inventory (ASI) had been completed by a number of both first- and second-year HND students in October 1992. It was also completed by the new intake to the extension degrees in October 1994. As was expected the results for the two groups were similar for all the constructs and the differences were not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The general picture was of fairly low scores on the meaning approach and high scores on the reproducing approach. Hidden within these figures were a number of individuals with high meaning scores, but who also had relatively high reproducing scores.

On the basis of these two sets of ASI scores, and the Business, Sport and Recreation degree’s end of year evaluation, the ‘three degrees’ team identified the following as the requirements of the induction programme for ex-HND students:

• organizational issues – this includes the way the course operates, assessment, course regulations, the personal tutor system, personal issues like time management and the personal portfolio;

• study skills – the need to adopt more effective study habits than were exhibited on HND;

• course philosophy – the courses were designed round the image of the ‘reflective practitioner’ or Capability’ concept where the student takes responsibility for their own learning. This is somewhat different to the paternalism of the HND.

The First Induction Programme

Approach

The first induction programme was designed and prepared by a small group comprising the course leaders, the HND common skills coordinator, and two other staff. The student representatives from the previous year’s Sports degree were consulted before the group had a brainstorming session to derive the initial programme. The draft was then circulated to the whole team for comments and volunteers to staff the programme were requested. Following this, the final programme was decided upon. It was not considered necessary to organize a formal induction for the level three Sports group.

Structure

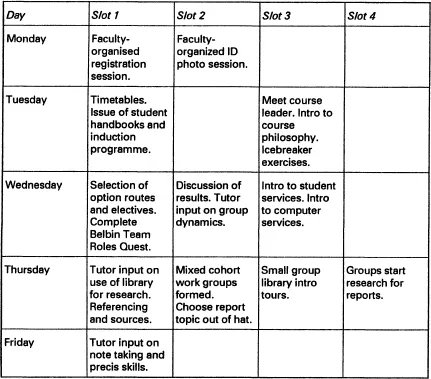

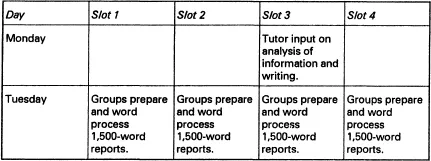

The faculty requires all the students to register, and to be introduced to student and computer services and the libraries before they are released to course-specific inductions. The necessity to comply with these requirements and the number of issues that needed to be included in our specific induction programme could not be accommodated in a single week. In addition, the research into student learning has shown (Entwistle and Ramsden op.cit.) that too pressurized an environment will lead students to fall back into a surface approach to learning. A two-week induction programme was therefore scheduled. This allowed a reasonable amount of self-managed time to be included.

Content

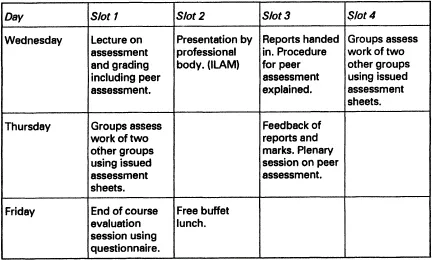

As mentioned earlier, the programme was intended to try to encourage students to adopt a more meaning approach to studying as well as making explicit the course philosophy. A major element in this philosophy is to encourage students to take an active role in the process of assessment. With this in mind, a session on the process of assessment and grading and an exercise in peer assessment was scheduled.

Table 8.1 Induction Programme 1 – Week One

Table 8.2 Induction Programme 1 – Week Two

Evaluation

Following the induction programme, the team undertook an evaluation exercise using student questionnaires; the results can be seen in Appendix 1. Overall the team were disappointed that the students were so critical of the programme. Reflecting on this, the team came up with the following observations:

• The induction programme lacked pace and there was too much free time.

• Students perceived that they were ‘old hands’ and therefore had little to learn about ‘studenting’ skills. Many students showed a lack of commitment to the induction programme.

• A number of the staff perceived the programme as the course leaders’ problem’ and hence gave it a low priority. Some even did not turn up for their timetabled sessions.

• There was dissatisfaction with the teaching accommodation.

• The use of peer assessment was a failure.

• The level three students felt that they needed an induction programme too.

• The careers service felt that students were not utilizing opportunities for summer placements or job search assistance.

The Second Induction

Approach

Taking on board these observations the course leaders felt that the approach to the following year’s induction needed to be radically different. Abandoning the induction programme altogether was not a viable option, but the evaluation highlighted serious deficiencies that needed to be rectified. Consequently the approach to the second induction programme was rather different.

First the course leaders arranged an informal meeting with the student representatives for the three courses away from the university campus. The aim of this meeting was wider than induction. It was felt important to explore the perceptions of the course and those issues that were important from the perspectives of both students and staff. Issues that were discussed included the role and responsibilities of student repr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Section one: Systems and Structures to Enable Student Learning

- Section Two: Strategies and Support for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Teaching and Learning

- Conclusions

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Enabling Student Learning by Sally Brown,Gina Wisker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildung Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.