- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intermodal Freight Transport

About this book

This book provides an introduction to the whole concept of intermodal freight transport, the means of delivering goods using two or more transport modes, recounting both European experience and UK developments and reporting on the extensive political influences on this form of transport. This is placed into context with reference to developments in North America and Asia.

Detailed explanations are given of the road and rail vehicles, the loading units and the transfer equipment used in such operations. In particular, the role of the Channel Tunnel in the development of long-haul combined transport operations between the UK and Europe is considered.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & Landscaping1

What Is Intermodal Freight Transport?

Intermodal freight transport, as previously outlined in the Preface, is the concept of utilizing two or more ‘suitable’ modes, in combination, to form an integrated transport chain aimed at achieving operationally efficient and cost-effective delivery of goods in an environmentally sustainable manner from their point of origin to their final destination.

While some freight movements may use, and justify the use of, a number of different transport modes, such as road, rail or inland waterway or either shortor deep-sea shipping, thus making them multimodal operations, in the majority of instances efficient movements are invariably achieved by the use of just two modes: most commonly road haulage collection and final delivery journeys combined with a railfreight trunk-haul journey, what is known as a ‘combined road–rail’ operation. However, where operational circumstances dictate or a feasible alternative option is available, road haulage or rail freighting may be combined instead with an inland waterway journey via river or canal, or with a short-sea shipping (SSS) operation, typically a coastal or a cross-Channel sailing. Combined transport operations involving either road haulage or rail freight in conjunction with deep-sea container services or with an airfreight operation also feature in intermodal and multimodal scenarios, albeit the latter occurring in only a relatively small number of instances and small scale in terms of the freight volumes shipped.

The word ‘suitable’ in the context used above may have a number of alternative connotations. It is possible in a given set of circumstances that cost alone will determine the choice of mode or modes, but frequently other considerations are decisive. For instance, operational practicalities like frequency of service, speed of delivery, the availability of special handling facilities, the ability to meet particular packaging requirements, security considerations or the sheer volumes of freight to be moved may be the determining factors, or indeed it may be that a number of these various service ‘pluses’, in combination, produce the ideal solution. But other less tangible issues may also enter the equation such as the need to follow corporate environmental policies or to assuage a shipper’s social conscience.

Freighting by one of the intermodal or multimodal combinations mentioned above is the alternative, of course, to consigning loads for the whole of their journey by a single mode, as is the case with some 62 per cent of domestic freight moved in Great Britain (according to the Department for Transports’ (DfTs’), Transport Statistics for Great Britain – 2004 , publication) for example, which is transported by road. It is a fact that the haulage of goods by road from their source direct to their final destination remains the preferred method in the majority of cases, and it is this preference which those individuals, corporate bodies, and government departments alike who champion the cause of intermodal transport are trying to break down.

Since by far the largest proportion of freight traffic commences and ends its journey on the back of a lorry, intermodalism is principally understood to mean the use of an alternative mode to undertake the middle, long-haul, or trunk, leg of the journey. Typically this involves trans-shipping the unitized load from a lorry at a railhead, inland waterway terminal, or at a seaport, for onward shipment by rail, inland waterway barge, sea-going ship, and then trans-shipping it back again onto a lorry for the final delivery of the leg to the customer; that is, the consignee. In some instances, as we shall see later, it is not just the unitized load that is trans-shipped, but the whole road vehicle, or at least its semi-trailer, which is loaded aboard a rail freight wagon, an inland waterway barge, a short-sea vessel, invariably a roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) ferry ship, or an ocean-going ship for onward transportation.

No matter what the particular freighting arrangement is, the essence of the whole operation is to utilize the key characteristics of each individual transport mode to its best advantage. The lorry has the benefits of immediacy and flexibility in its favour plus the ability to affect collections and deliveries of goods from locations that have no rail sidings or waterway quays for loading. Rail freighting offers a lower-cost alternative for multiple loads carried over longer transits and a much less-polluting effect on the environment, as does barge traffic shipped on the navigable rivers, and canals of inland waterway networks. Thus road haulage in any combination with either rail freighting, inland waterway, short-sea, or coastal shipping may prove to be the most viable option, both economically and operationally. But in certain cases, particularly where no RO-RO vehicle ferry service, road or rail tunnel facility exists, shipping by container vessel may be necessary, and especially for trans-global freight movements.

As this book will show, there are politically motivated policy moves within the European Union (EU) to find ways of switching as much freight as possible from road onto the rail, and to a lesser extent onto the waterway, networks. This is seen as a beneficial antidote to the adverse impact of heavy lorries on traffic flows both on motorways and in urban areas, although the latter is something of a misconception since heavy lorries will still be required to serve many road–rail terminals, and the substantial numbers of freight originators and recipients located in urban areas who are not rail connected (e.g. most small businesses and High Street retail outlets). The European Commission (EC) talks of the ‘complementary’ qualities of road and rail transport, and it is this aspect of complementarity that it believes to be the key to transport policy for the future. However, we should not overlook the keen interest now being shown in Brussels (i.e. in the EC’s Directorate-General for Energy and Transport – DG VII) in revitalizing the role of inland waterway and short-sea and coastal shipping, as we shall see in greater detail in Chapter 8.

Also to be gained from a modal switch are perceived social benefits, such as reduced air pollution, resulting from fewer heavy lorries, the theoretical saving in road accidents – according to the European Commission’s Community Road Accident Database (CARE), there were some 40 000 road accident deaths in the 15 Member State-EU in 2002 costing 160 billion euros (£115 billion at the November 2004 currency exchange rate) – and the separation of freight movements from a ‘people’ environment, which roads substantially are and rail, largely, is not.

The economic concept of road–rail combined transport is that it keeps the expensive element of the road haulage operation, namely the operation of the road vehicle tractive unit and the driver, fully utilized on short-haul, road-borne collections and deliveries, for which it is ideally suited and sufficiently flexible to go anywhere at any time to suit individual requirements, while the less expensive part of the operation, namely the loaded semi-trailer, swap body, or container, is sent unaccompanied on the long-haul leg of the journey by rail. Given that the rail-haul leg is long enough to justify the switch from road (generally it needs to be at least 500 kilometres, although new thinking suggests that short-distance intermodalism becomes viable for distances in excess of only around 200 kilometres), this produces benefits by way of savings in journey time, reduced consumption of carbon fuel, less pollution from exhaust emissions, reduced heavy traffic flows on motorways, and, theoretically, fewer road accidents. The road haulier benefits from not having his truck and driver missing for hours, if not days, on end, pounding up and down the roads of the UK or across Europe to meet customer deadlines, and incurring wear and tear, damage, driver subsistence costs, plus the well-known risks of penalty for speeding, traffic, and other law infringements. Given the right combination of circumstances, the goods transported on the long haul by rail rather than by road will be at their destination sooner since trains, unlike truck drivers, are not obliged by law to park up en-route for a statutory night or weekend rest period.

The essence of efficient intermodal transport lies in the use of a unit-load system capable of transfer between road, rail, and other transport modes, and which allows for the collection of consignments by, for example, a road vehicle followed by a trunk-haul journey by rail or waterway and a final road-borne delivery without trans-shipment or repacking of the load itself. Standard loading units take the form of either road-going semi-trailers conforming to standard dimensions and designed to be piggybacked aboard rail wagons, or more commonly, swap bodies and shipping containers built to international (ISO) standards which are fully interchangeable between a variety of road vehicle combinations, rail wagons, river and canal barges, and sea-going ships. In all circumstances the load remains intact and secure within the loading unit which is lifted or transferred by purpose-built equipment onto a rail wagon, a canal barge, or into the hold of a ship and then back to a road vehicle at the end of the trunk-haul leg of the journey.

Such systems provide greater flexibility for the customer, who may be either the consignor or the consignee, by allowing goods to be loaded or unloaded at his premises in the conventional manner without changing the current practices applied to his domestic or local traffic. It also assures his piece of mind if, having seen his freight securely stowed and sealed in an intermodal-loading unit, he knows that it will not be disturbed again until it reaches its final destination, unless it is to comprise part of a groupage load. The principal benefits of unit-load intermodalism is that it can provide:

- lower transit costs over long journeys;

- potentially faster delivery times in certain circumstances (these obviously need to be individually assessed for particular cases);

- a reduction in road congestion (a major beneficial factor in these modern times);

- a more environmentally acceptable solution to congestion and related problems (such as the emission of noise and fumes, the damage caused to the built environment by vibration and so on);

- reduced consumption of fossil fuels since the long-haul section of the route is more fuel efficient;

- safer transit for some dangerous products.

1.1 The background to intermodalism

The practice of transferring road trailers and road-borne containers onto rail wagon for trunk haulage has existed since the earliest days of rail. The hardware has obviously changed over the years and today’s domestic and international journeys are much longer than the domestic operations of yesteryear, but the basic principles remain the same. Simple wooden box containers, used even in the days of horse-drawn transport, have given way to the latest form of steel shipping container and swap body built to international (ISO) strength and dimensional standards, while road-hauled semi-trailers have developed from simple two-wheeled affairs with ‘cart-like’ springing – as drawn by the well-known railway ‘turn-on-a-sixpence’ three-wheeled Scammell mechanical horse – into high-capacity multiaxle, sophisticatedly-suspended units. In fact, present-day articulated semi-trailers are highly sophisticated pieces of equipment, cushioned with air suspension and equipped with airbrakes, and capable of safely carrying a 30-odd tonne laden ISO container or swap body within the current legal maximum vehicle gross weight limit of 44 tonnes and at the maximum permitted speed; namely 56 miles per hour (mph) for speed-limited heavy trucks. The parallel development of technically sophisticated lifting and transfer equipment enables these loading units and semi-trailers to be transferred rapidly and efficiently from road to rail or barge for long-haul transport, and back again for final delivery.

Intermodal road–rail transport as we know, today it has been widely and successfully employed in mainland Europe for many years; especially notable, for example, being the French Novatrans ‘Kangaroo’ system for the piggyback carriage on rail of unaccompanied road-going semi-trailers and the similar German Kombiverkehr system in which swap bodies, piggyback semi-trailers, and complete road vehicles are also carried by rail on what is known as a rolling motorway system.

1.2 The impact of the Channel Tunnel

It is useful to consider here the impact of the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France, which opened in May 1994, on the longer-haul potential of UK–Europe intermodal freighting. Eurotunnel, the Tunnel operator, originally estimated that it would carry around 400 000 heavy goods vehicles annually on its drive-on/off freight shuttle service, a target which, in 2003, it significantly exceeded with 1 284 875 trucks being carried – in fact, capturing some 40 per cent of the total cross-Channel driver-accompanied freight traffic market. By September 2003 Eurotunnel was operating up to seven freight shuttles each way every hour during peak periods. However, these carryings have somewhat diminished since these figures were published with a 4 per cent reduction in truck shuttles reported for the third-quarter of 2004 and a 2 per cent loss of market share.

Besides this lorry traffic, substantial volumes of rail-borne inter-Continental swap body and container traffic passes through the Tunnel from inland freight terminals in the UK to international destinations via Europe’s 241 000-kilometre rail networks. In 2003 this amounted to 1 743 686 tonnes; albeit this tonnage was some 40 per cent less than its carryings in 1999 and lower than for both 1998 and 1997, largely due to its slow recovery from the widely publicized problems of 2002 caused by the influx of illegal immigrants into the UK who were stowing away on the freight trains from the French side of the Tunnel, resulting in many service cancellations. Encouragingly, however, by November 2004, Eurotunnel had reported a 7-percent increase in its rail-freight carryings through the Tunnel.

These statistics show the Tunnel to have been an important catalyst for increased interest in the development of intermodal services between the UK and Europe. Furthermore, additional encouragement was provided by legislative measures permitting heavier lorries for use in intermodal transport operations. From March 1994, 44-tonne lorries (compared with the previous domestic maximum weight limit of

38 tonnes) were allowed on UK roads, initially for use only in road–rail transport operations to and from rail terminals, subject to specific technical and administrative conditions, but since 1 February 2001

44-tonne vehicles have also been permitted, unconditionally, for general-freight carrying in the UK. This development proved to be a boon for Eurotunnel’s heavy-vehicle carryings since it encouraged greater interest among UK road hauliers in undertaking trans-European operations via the Tunnel. Another boost for Eurotunnel’s market potential share, although not yet, at the end of 2004, reflected in its carryings, was the addition of the 10 new Member States to the EU from May 2004; road hauliers from these countries being permitted to carry freight to and from the UK subject to meeting the necessary EU legal requirements relating to goods vehicle operation.

1.3 Freight transport growth

Continued development of intermodal transport between the UK and Continental Europe is, of course, dependent upon a growing freight transport market throughout the EU, the rest of Western Europe, and the former Eastern Bloc countries – now, largely, part of the EU. The EU expanded from its former 15

Member States in May 2004 with the admission of the 10 so-called ‘accession’ states; namely, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia, and Slovakia – increasing the potential market to some 480 million people – and is due to expand again in 2007 when Bulgaria and Romania expect to be admitted, with Turkey following at some point in the future. There is no doubt that with all these new Member States, the expanded EU will provide colossal opportunities for the development of intermodal freight transport – in October 2003, European Commissioner in charge of transport, Sna Loyola de Palacio, said that goods transport would increase by 36–40 per cent in the next decade and that besides the new infrastructures needed, alternative modes of transport would also have to be developed. Certainly, if she is right, which undoubtedly she is, it would be a frightening prospect if the resultant increase in intra-European trade and consequently its transportation needs were to be funnelled onto the EU’s existing heavily congested road network.

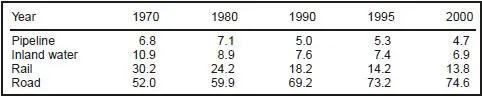

Fig. 1.1 EU Freight transport by mode statistics 1970–2000 (in tonne-kilometres %).

(Source : EU Energy and Transport in Figure 2003, via Internet.)

(Source : EU Energy and Transport in Figure 2003, via Internet.)

We have, of course, already seen significant transport growth within the EU over past years, but it has not been shared equally between modes. While road transport has grown to account for roughly 75 per cent of all intra-Community goods transport activity, in the same period (i.e. 1970–2000) rail transport decreased in relative terms from 30.2 to 13.8 per cent. The inland waterways of Europe, as Figure 1.1 shows, also declined from carryings of 10.9 per cent of traffic to just 6.9 per cent, albeit since 2000 we have begun to see a reversing trend in the fortunes of this mode, while SSS now carries some 40 per cent of all trade within the EU.

The trend towards the growth of road freighting in favour of other modes as shown in the table above continues. In its 2001 White Paper, European Transport Policy for 2010: Time to Decide , the EC predicted that by 2010 heavy goods vehicle traffic will have increased by nearly 50 per cent over its 1998 level. And with the strong economic growth expected in the acceding countries (i.e. the 10 countries ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Front cover captions

- Dedication

- Disclaimer

- List of illustrations

- The Author

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 What Is Intermodal Freight Transport?

- 2 UK and EU Policies for Intermodal Transport

- 3 Intermodal Developments in the UK

- 4 Intermodal Transport in Europe

- 5 Intermodalism in North America and World Markets

- 6 The Road Haulage Role in Intermodalism

- 7 Rail-Freight Operations

- 8 Inland Waterway, Short-Sea, and Coastal Shipping

- 9 Environmental and Economic Issues

- 10 Grant Aid and Government Support

- 11 Intermodal Networks and Freight Interchanges

- 12 Intermodal Road and Rail Vehicles and Maritime Vessels

- 13 Intermodal Loading Units, Transfer Equipment and Satellite Communications

- 14 Carrier Liability in Intermodal Transport

- 15 Intermodal Documentation and Authorizations

- 16 Customs Procedures

- 17 International Carriage of Dangerous Goods

- 18 Safety in Transport

- Glossary of terms

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intermodal Freight Transport by David Lowe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.