eBook - ePub

Understanding Unemployment

New Perspectives on Active Labour Market Policies

This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book argues that unemployment is symptomatic of an inherently inefficient labour market founded on structured inequalities of locality, sex, race and age. It provides a multidisciplinary explanation of why unemployment has been a continuing crisis, suitable for students in many disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Understanding Unemployment by Eithne Mclaughlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

TOWARDS ACTIVE LABOUR MARKET POLICIES: AN OVERVIEW

Eithne McLaughlin

A CRISIS OF UNEMPLOYMENT?

By the late 1980s, unemployment was becoming a forgotten policy issue in Britain. This was not because there was little unemployment, but because unemployment had been redefined as a residual and individualized problem, for which the enterprising free-market Thatcher administration had no direct responsibility. There was, then, no crisis. This book aims to provide a well-informed, easily understandable and up-to-date explanation of why unemployment has been a continuing crisis for the British and Northern Irish economies, as well as for the many people, adults and children, who have had to experience the effects of unemployment. In this and subsequent chapters the emphasis is on an analysis of the structure of unemployment, and through that the identification of a responsible set of policies which could address this long-running crisis. The purpose of this first chapter is to provide an overview of the analyses in the context of a critique of approaches to unemployment in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Unemployment levels

Is unemployment still the most serious economic problem facing the UK? One way of answering this question is to compare unemployment levels over time and between countries. Unlike the United States, though in common with many European countries, Britain had found it possible to achieve low unemployment rates for long periods of time since 1945. For most of the period unemployment was substantially below 5 per cent, reaching a low of just over 1 per cent in the mid-1950s. In the 1960s and the 1970s unemployment did tend to rise but it was a slow process. As Jackman (Chapter 3) asks, if in the twenty-five years after the Second World War, the unemployment rate in Britain was generally less than 2 per cent, why is it 8.5 per cent and rising in 1991? Why, too, did unemployment rise faster in the UK than in other European countries? In the early 1990s, for example, unemployment in the UK rose by 31 per cent, compared with an increase of 4 per cent for France and a drop of 13 per cent in (West) Germany (Eurostat, July 1991).

Why too has UK unemployment tended to stick, that is, not to fall back once a new peak has been reached? Both White (Chapter 2) and Jackman (Chapter 3) discuss the reasons for the ‘sticky’ nature of British unemployment. White points to a higher level of wage rigidity in Britain combined with a reliance on a more unqualified and low qualified work-force compared with our European counterparts. Jackman, too, points to the inflexibility of structural skill imbalances and the minimal influence of unemployment levels on wage determination. This perspective is very different to the one espoused by the Conservative administrations of 1979 onwards, a point which will be taken up further in the next section.

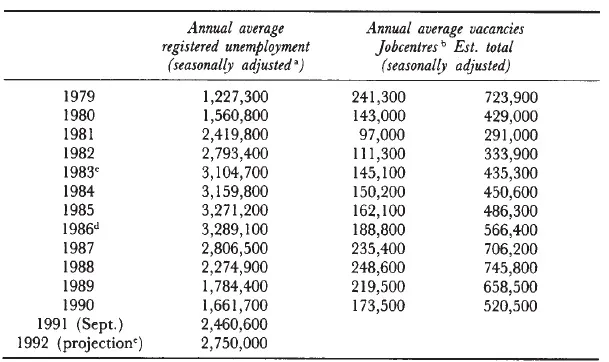

What of unemployment levels in the future? Table 1.1 shows registered unemployment levels in the UK between 1979 and 1991 together with a projection for 1992. Even the decrease in registered unemployment in 1988– 90 only brought unemployment levels down to 1980/1 levels, themselves historically high. There is little evidence to sustain a belief that unemployment will fall below 2 million by the mid-1990s (National Westminster Bank forecast, May 1991) and some forecasters argue that it will be considerably higher. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research's quarterly review in May 1991 predicted that registered unemployment would rise to 2.75 million by mid-1992 and remain at 2.5 million or above for the rest of the century. In comparative terms, across the EC, by 1992, only Spain, Ireland and the former East Germany are expected to have higher unemployment than the UK.

As Table 1.1 also shows, vacancy levels fell sharply in 1990 and this fall is likely to continue. Although inflation fell to around 4 per cent by the end of 1991/beginning of 1992, this has been accompanied by falls in manufacturing investment of 15 per cent in 1991 and an anticipated 7 per cent in 1992. For the first time since records began, manufacturing firms employ fewer than 5 million people (4,945,000 in Jan. 1991, Dept of Employment Gazette).

Measuring unemployment

In fact, the full extent of both current and future unemployment is not well measured by the data in Table 1.1. The definition and measurement of unemployment has been a contentious issue throughout the 1979–91 period. Registered unemployment as shown in Table 1.1 includes only those receiving social security benefits by virtue of their unemployed status. Therefore this method of measuring unemployment is more dependent on social security regulations and entitlements than on unemployment per se.

Throughout the 1980s, new restrictions on social security benefits for unemployed people were introduced at various points (see Chapter 11,

Table 1.1 Unemployment and vacancy levels, 1979–91 UK

Source: Dept of Employment Gazettes

Notes:

a Figures prior to 1982 are estimates of seasonally adjusted unemployment.

b Excluding Community Programme vacancies in GB.

c Figures after April 1983 no longer include some men aged 60 or over who choose not to sign on for work (between April 1983 and August 1983 this reduced the unemployment count by an estimated 161,800).

d Change in compilation of unemployment statistics from February 1986 means that later figures are not directly comparable with pre-1986 figures (this change reduced the total UK count by an estimated 50,000 on average).

e NIESR projection, May 1991.

Notes:

a Figures prior to 1982 are estimates of seasonally adjusted unemployment.

b Excluding Community Programme vacancies in GB.

c Figures after April 1983 no longer include some men aged 60 or over who choose not to sign on for work (between April 1983 and August 1983 this reduced the unemployment count by an estimated 161,800).

d Change in compilation of unemployment statistics from February 1986 means that later figures are not directly comparable with pre-1986 figures (this change reduced the total UK count by an estimated 50,000 on average).

e NIESR projection, May 1991.

and next section). In addition, the claimant count has excluded all those on government-supported training schemes, such as Employment Training and Youth Training. In early 1991, the numbers of people excluded from the claimant count because of participation on training schemes totalled around 610,000.

The cumulative result has been an increasing disparity between the claimant count and more direct measurements of unemployment. So, for example, as Pissarides and Wadsworth (Chapter 4) show, the claimant count and the Labour Force Survey rates of unemployment were very similar in 1979, but by 1989 the two rates had moved apart, with only 68 per cent of unemployed people in the LFS also being claimants. This systematic under counting has made unemployment among certain population groups particularly invisible. Only 40 per cent of unemployed women in the 1986 LFS were also claimants and hence included in the claimant count. The biggest single factor accounting for this under-representation is the lack of independent entitlement to means-tested benefits of unemployed married or cohabiting women. In addition to unregistered unemployment, captured by definitions based on those seeking work rather than those receiving benefits, Metcalf (Chapter 9) points out that there may by a considerable level of what she calls ‘hidden unemployment’. This is caused by the acceptance as legitimate of some, but not other, barriers to employment. These barriers include the constraints of caring for children and disabled adults, low pay and discouragement from job search—the latter two being caused by labour market segmentation and discrimination against women (particularly mothers), ethnic minority groups, older people and people with disabilities.

By the early 1990s, the number of people in either registered or unregistered unemployment in Britain and Northern Ireland probably approached nearly 4 million, after people on government training schemes and married and cohabiting women with no social security entitlements are added to the claimant count. Such a figure clearly demonstrates a continuing crisis of unemployment in Britain and Northern Ireland (see also Gordon 1988). Were the hidden unemployed to be added to this count, the figure could well rise to nearly 10 million, assuming half of those now classified as non-participants but still of working age (see Chapter 9) represent hidden unemployed rather than ‘true’ non-participants.

The cost of unemployment

The cost of this systematic underutilization of the labour force is considerable, resulting in a national output lower than would otherwise be the case, poor returns on public investments in education and training, and of course, income and opportunity inequities between population groups. Registered unemployment alone carries a massive cash price tag. For example, the cost in total public expenditure of 1991 levels of registered unemployment was nearly £21 billion. Interestingly, this figure was arrived at from two very different sources with different perspectives on both the causes of, and the solutions to, unemployment (the Unemployment Unit, September 1991, and the Adam Smith Institute, November 1991). In terms of public expenditure planning, each 100,000 increase in the registered unemployment figure above the 1.75 million forecast in spending plans for 1991 onwards, means the Treasury will have to find an extra £320 million.

It is argued by all the contributors to this book that, without a renewal of government commitment to active labour market intervention, there is little hope of even registered unemployment levels dropping to pre-1979 levels. The implications of continued high levels of unemployment for public expenditure on other areas of concern (such as the health service) are very serious, as are the equality of opportunity and economic welfare implications for women, ethnic minority people, older people and people living in high unemployment areas (an issue discussed later in this chapter). Interpreting these levels of unemployment, and their associated costs, as anything other than a crisis, is only possible by a massive abdication of state responsibility in economic affairs.

MONETARISM AND UNEMPLOYMENT POLICY IN THE 1980s

The 1980s have been characterized by just such an abdication of state responsibility. Twenty years ago, when unemployment rose to approximately one million for the first time since the end of the Second World War, the shock-waves prompted a policy U-turn by the Heath government. In current times, however, government has succeeded in distancing itself politically from responsibility for high unemployment levels. By 1985, unemployment was treble that of 1979, and by 1991, it was double 1979 levels. Manufacturing output was experiencing its second slump and was almost back to its levels of 1979, and the prospects of the UK ever being in the black seemed remote. Yet remarkably, at a fundamental level, the Government has remained unchallenged. A new orthodoxy has gripped what little macro-economic debate remains:

the great traditional goals of economic policy, with the important exception of price stability, are disappearing from view. In particular, growth and unemployment are ceasing to be seen as objectives of policy, but rather as natural events, like hurricanes or snow, which are news, certainly, but which the government can neither predict nor control.(Professor Wynne Godley, ‘Terminal Decay’, New Statesman and Society, 15 March 1991)

Discussing the government's biggest failure—unemployment—has thus become almost taboo, as unemployment is presented as fluctuating like the weather and beyond government control. In 1991, the Chancellor of the Exchequer stated bluntly that rising unemployment was a ‘price worth paying’ for lower inflation. The concept of unemployment paying for price-stability is a critical one; 1980s government policy towards the economy has been dominated by the elevation of price-stability to the (sole) objective of government. In itself, price-stability is a worthy objective, particularly in ageing societies such as Britain where a growing proportion of people have to depend on fixed incomes. However, price-stability is not an end in itself; it must be weighed against the long-term and short-term costs incurred by single-minded pursuit of this objective. Even in the short term, is a 2 per cent fall in inflation worth half a million more people joining the registered unemployment count?

The problem has been that Conservative governments since 1979 have answered yes to this question. The election of the first Thatcher government in 1979 represented a fundamental stepwise shift in economic policy-making on a number of fronts, not least of which was the total abandonment of any kind of commitment to the management of labour demand. This involved the adoption of an exclusively supply-side interpretation of the causes of unemployment. ‘Labour market rigidities’ and ‘barriers to growth’ were identified as trade union power, centralized forms of collective bargaining and pay determination, high wages, generous social security benefits, employment protection legislation, high rates of income tax and an oversized public sector. All of these were held to produce malfunctions and distortions in the market place. The 1985 White Paper Employment: the challenge for the Nation exemplifies this perspective on unemployment.

As Deakin and Wilkinson point out (Chapter 11), it was the adoption of a brand of monetarism from across the Atlantic, based on nineteenth-century theories of how money moves in the economy, which provided the rationale for this approach to unemployment. According to orthodox monetarist economic theory, both wage differentials and unemployment are caused by impediments to the operation of a ‘free’ labour market, originating in the power of organized groups and in the extended regulatory role of the welfare state. The state is seen as contributing to the rigidity of the labour market, through social security programmes which make unemployment attractive by increasing out-of-work incomes (Minford 1986), and by the provision of certain non-cash benefits and services free to all (for example, health care and education), regardless of family and employment status. Similarly the state contributes to the rigidities of labour market organization through individual labour law regulating the contract of employment and through collective labour law supporting trade union rights (Rowley 1986; Hanson and Mather 1989). Taxation, in the form of social charges upon employers and regulation of the contract of employment which inhibits effective bargaining, acts as a disincentive to the creation of jobs by employers.

Employment and unemployment inequalities are then caused by exogenous non-market factors, the key culprits being individual ‘choice’, personal (in)efficiency, excessive labour power and the political intervention of the state. If the labour market was protected from these non-market factors, the market would be free to tend towards equilibrium and, concurrently, equality of exchange between workers and employers as market wage rates fell into line with individual effort and productivity. A programme of deregulation designed to remove market imperfections will therefore offer the most effective policy approach to the labour market. As Deakin (1989) argues, however, evidence which challenges the core tenets of the theory has been excluded and reclassified as ‘non-economic’ thus negating the need for significant modification to the central tenet—that the market allocates labour to its most efficient uses and rewards it accordingly.

It is within this framework that government labour market policy since 1979 becomes explicable, namely abandonment of attempts to regulate the level and nature of labour demand and deregulation of the supply side. This policy had three main thrusts: social security changes, promotion of low-paid work, and deregulation of the employment contract (see Chapter 11). Within the social security field, the 1980s were characterized by cuts in the levels of unemployment benefit relative to wages, lengthening of the qualification period for unemployment benefit, increases in the period of disqualification from benefit following ‘voluntary’ unemployment, widening of the range of jobs claimants were required to look for and accept, provision of proof that claimants were actively seeking work, and removal or reduction of social security rights for young people. Promotion of low-paid work has involved rebates of national insurance contributions for the low-paid and subsidies towards the employment of young people, together with an extension of in-work benefits targeted at the low-paid...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- FIGURES

- Tables

- NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

- Preface And Acknowledgements

- 1 Towards Active Labour Market Policies: An Overview

- 2 Labour Supply And Demand In The Nineties

- 3 An Economy Of Unemployment?

- 4 Unemployment Risks

- 5 The Role Of Employers In The Labour Market

- 6 Psychological Or Material Deprivation: Why Does Unemployment Have Mental Health Consequences?

- 7 Social Security And Labour Market Policy

- 8 Unemployment, Marginal Work And The Black Economy

- 9 Hidden Unemployment And The Labour Market

- 10 Regional And Local Differentials In Labour Demand

- 11 European Integration: The Implications For Uk Policies On Labour Supply And Demand

- Index