![]()

Chapter 1

Politics in an Age of Manufactured Images

In his Politics (1995), Aristotle wrote that humankind is created to live in the political state. Despite the many years that have since passed, this statement is still valid and has inspired many theoreticians and practitioners studying the life of people under many social systems. However, it has been modified many times in order to keep it up to date with the changing picture of humankind’s conditions. In social psychology, the statement was popularized by Elliot Aronson (1992), who coined the notion of man as a social animal. Sociology, and particularly sociology of politics, treats an individual as, to use Seymour M. Lipset’s (1981) term, homo politicus. These concepts point to a person fulfilling his or her goals and desires only when he or she belongs to a group, namely society. Therefore, by belonging to such a group, he or she should also obey the rules and standards that exist there.

Democracy is currently the main form of people’s organization of themselves within state structures in the world. Despite its common criticism, this system is spreading across the world and is becoming the final destination for many societies under authoritarian power (see Huntington, 1991). According to Robert A. Dahl (2000), in order to exist and develop, every modern democracy needs the following six institutions:

1. Elected representatives. They constitute the parliament elected by citizens, and their major task is to control the government’s decisions.

2. Free, honest, and frequent elections. People are neither forced to participate in such elections nor are they forced to elect a given person or political party.

3. Freedom of speech. Citizens have the right and absolute freedom to express their political views without fear of punishment. They can criticize their representatives, government, or system.

4. Access to various sources of information. Citizens have the right to seek political information from many different sources, independent of the power or other monopolies present.

5. Freedom of association. Citizens, if they wish, should have a chance to establish independent associations and organizations, including political parties and interest groups.

6. Inclusive citizenship. This means that no adult having the citizenship of a given country may be deprived of the rights that others enjoy and that are essential for democratic institutions.

Participants in political life are most interested in the first two democratic institutions mentioned by Dahl (2000): elected representatives and free, frequent, and honest elections. These two elements of democracy are the main areas of research involving citizens’ voting behaviors and ways of influencing these behaviors through political marketing.

The interest in citizens’ voting behaviors is influenced by very practical motives: What do I need to do to win in the elections? How do I speak so that people can understand me and support me? What do I say in order to make people vote for me? To whom should I speak—to everybody or only to “selected” groups? Why do people vote the way they do? Why do they support this particular party? Many questions can be asked, but getting convincing answers to them is much harder.

An interesting phenomenon of modern civilization is the development of marketing methods for influencing voting behaviors, which stress the importance of creating a particular image of a fragment of political reality in voters’ minds in order to shape it as freely as possible. The evolution of this branch of science has been quite long and has required the development of a viewpoint that would embrace an idealistic philosophy. The philosophical roots of modern political marketing can then be found in the Kantian epistemological theory, from which the currently used term cognitive sciences is derived.

The most important element of this practice is cognitive psychology, through which one can understand the techniques of influencing voter behavior. Therefore, before presenting the cognitive foundations of modern methods of political persuasions, one should take a brief look at the evolution of the views leading to modern research on forming politicians’ and political parties’ images.

DECLINE OF SOCIAL CLEAVAGE VOTING

The oldest studies on voting behaviors are represented by the sociological approach also called the sociostructural method. As its starting point, it takes the assumption that one’s main reason for voting is one’s sense of belonging to a social community. Examples of such communities may include ethnic, religious, or professional groups, or a social class, all of which point to the collective character of voting behaviors. In other words, it is individuals who vote, but their preferences are determined by their belonging to a given group.

The pioneer studies in this area are represented by panel discussions conducted by American academics from the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University and directed by Paul F. Lazarsfeld (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, Gaudet, 1944; Berelson, Lazarsfeld, McPhee, 1954). The first study was conducted in Erie County (Ohio) during the presidential elections in 1940, when Franklin D. Roosevelt (Democratic Party) and Wendell Wilkie (Republican Party) were competing. A second series of the studies was conducted during the presidential elections in 1948 in the town of Elmira (New York), when Harry Truman (Democratic Party) and Thomas Dewey (Republican Party) were competing. Despite the fact that Lazarsfeld is known as a sociologist, his main academic interest was the field of political marketing (see Chaffee, Hochheimer, 1985). Such interests determined his approach to analyzing voting behaviors as a specific type of consumer decision. However, the major conclusions that Lazarsfeld’s team reached was that supporting a given presidential candidate is a group process, consisting of the following: common preferences in families; similar voting decisions among friends, colleagues, and neighbors; the strong influence of opinion leaders; and little influence of the mass media.

The sociostructural model of voting behaviors therefore assumes that an act of a citizen’s voting is conditioned by their place in social structures. Sociological variables show a united set of interests shaping political coalitions and defining the level of a party’s fit to the needs of various groups of people. The voters are treated not as individuals but as a community of views determined by their social position (social stratification) and acceptance of the same values. Following such assumptions, researchers consider the broadly understood demographic and sociological variables as the main voting-decision determinants (see for example Agnew, 1996; Pattie, Johnston, 1998; Lipset, 1981).

According to the sociostructural perspectives, the goal of each citizen is to recognize their social status. Generally speaking, it may then be said that one’s political activities are to some extent determined the day he or she is born. For example, if a boy is born into a working-class family living in the suburbs of a large industrial town, it is most likely that he will support left-wing programs and parties.

Despite that sociological analyses still play an important role in explaining voting behaviors, it is believed that the assumptions they created were not valid at the moment in which they were formulated. Models based on demographic variables put an emphasis on the continuity and stability of voters’ behaviors. However, they are still unable to explain changes in voters’ preferences (Dalton, Wattenberg, 1993). Many researchers from different countries speak about the end of class divisions and the collapse of the class voting model (Dalton, Wattenberg, 1993; Johnston, Pattie, Allsopp, 1988; Riley, 1988). This model suggests that the working class supports left-wing parties and the middle class supports right-wing parties. However, this trend seems to be disappearing in all democratic party systems, though it can, to some extent, be helpful in predicting citizens’ voting behaviors.

Many scholars directly linked the decline of social cleavage voting to ongoing changes in the nature of Western societies (e.g. Inglehart, 1977; McAllister, Studlar, 1995). Virtually all industrial democracies have shared in the increasing affluence of the postwar economic boom. The embourgeoisement of the working class narrowed the differences in living conditions between class strata and attenuated the importance of class-based political conflict. The growth of the service sector and government employment further reshaped the structure of labor forces, creating new-postindustrial societies. These changes were paralleled by other shifts in the social structure. Modern societies require a more educated labor force and possess the resources to dramatically expand educational access. Changing employment patterns also stimulate increased geographic mobility and urbanization. The traditional closed community life was gradually supplanted by more open and cosmopolitan lifestyles.

Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg (1993) believe that these and other social forces transformed the social composition of the contemporary public from those of the electorates on which sociological models of voting behavior were based. The social class, religious, and community bases of social structure have been altered in equally profound ways.

A detailed analysis of the sociological approach will be presented in Chapter 4.

DECLINE OF PARTISANSHIP AND PARTY IDENTIFICATION

Until recently, partisanship was considered an important element of voting in democratic parties, and the only one in totalitarian countries. However, a number of modern studies on voting preferences conducted in the United States and Europe prove that the importance of voters’ partisanship for voting for a given candidate is systematically decreasing.

In the second half of the twentieth century, researchers studying political behaviors believed that the majority of voters knew whom they were going to support in political elections from the beginning of the campaign. Therefore, they would not be open to any persuasion during the political campaign. The small group of undecided voters turned out to be so minute that, despite their susceptibility to a party’s and candidate’s information policy, their significance was very low. This position, also accepted by party leaders, helped them to determine the concept of the party and of the product in planning their campaign. The concept changed only when the number of undecided voters and those changing their decisions during the campaign increased (see Wattenberg, 1995; Chaffee, Rimal, 1996).

Due to the increasingly visible polarization of the voting market into those decided and undecided, Stephen Chaffee and Rajiv Rimal (1996) presented their dichotomous model, which divides the voters into two major groups: (1) a large segment of those decided, and (2) a smaller but increasing segment of those undecided.

Taking into consideration people’s timing in making their decision to support a particular candidate, one may say that the voters in the first segment made these decisions a long time ago. They have a sense of belonging to a given party, agree with its views, and are therefore resistant to the actions of other parties, although they follow the campaign closely. The voters from the second segment have not made their decisions yet and are therefore more open and susceptible to voting communication. However, one may suspect that their indecisiveness results from their lack of interest in the election, which leads to media voting paradox. It means that even though undecided voters are more prone to the influence of the media, they are not in fact influenced by the media because they either pay no attention to it or disregard political news (Chaffee, Choe, 1980).

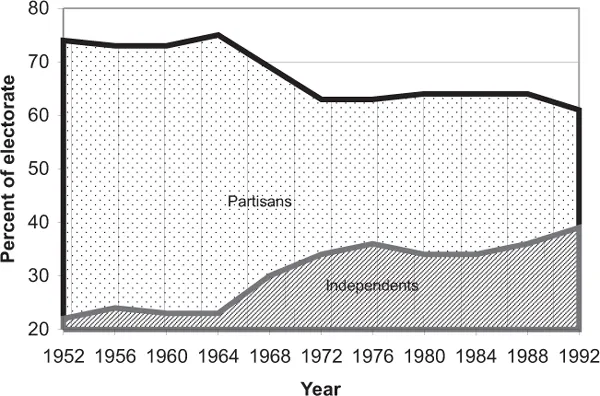

Chaffee and his colleagues believe that since 1950 the power of partisanship has been systematically decreasing and the number of voters making decisions during the campaign has been increasing. This is confirmed by Thomas M. Holbrook’s analyses (1996), presenting in detail the changes in partisanship on the American voting market between 1952 and 1992. They show a systematic decrease in the number of voters identifying themselves with the Democratic or Republican Party and an increase in the number of independent voters. (See Figure 1.1.)

A more detailed study on the formation of the undecided voters segment over several decades was presented by Bernadette Hayes and Ian McAllister (1996) for the voting market in Britain. The authors observe a systematic decrease in voters affiliating themselves with any political party since 1960. Indeed, the loyalty toward the two major British parties, the Conservative Party and the Labour Party, is decreasing. One of the reasons for this is a noticeable increase in domestic and foreign policies’ independence from party ideology. This leads to consistently fewer differences between the opposing parties in key issues of economic policy.

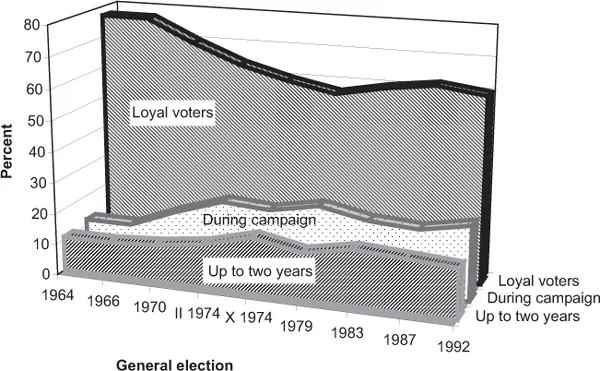

As time goes on, the segment of undecided voters is beginning to be more and more visible. According to Hayes and McAllister (1996), they are called “floating voters,” and are not connected with any party. In order to achieve election success, parties should pay particular attention to such voters and concentrate less on their “permanent,” loyal voters. The dynamics of the formation of voting segments, relative to the decision-making time between 1964 and 1992, is presented in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.1. Changes in partisanship 1952-1992. Source: Adapted from Miller W.E. and the National Election Studies (1994). American National Election Studies Cumulative Data File 1952-1992 [Computer File]. Sixth release. University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer]. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1991.

The figure shows three segments of voters: (1) voters loyal to a given party who made their decision quite early, (2) voters making decisions between general elections over the course of two years, and (3) campaign voters making their decisions only days before the elections.

One can clearly see that the number of loyal voters decreased from 77 percent in 1964 to 60 percent in 1992. On the other hand, the segment of undecided voters is growing very quickly. By 1992, it was already 24 percent of the individuals voting. This figure is important in light of the results of voting competition. One can then understand why, in recent years, so much investment has been made in the development of marketing techniques used during political campaigns. Private advertising agencies also participate in it, focusing on undecided voters. Such investments rapidly increase campaign costs. An estimated nine million pounds was spent on the Conservatives’ campaign in 1987, and although the record seemed unlikely to be broken, five years later it was ten million. A similar situation can be observed with the Labour Party, which in 1987 invested slightly more than four million pounds in its campaign. However, in 1992, its expenses almost tripled, exceeding seven million pounds.

FIGURE 1.2. The time at which voters decide how to vote, 1964-1992. Source: Adapted from Hayes and McAllister (1996).

One should note that Figure 1.2 illustrates changes strikingly similar to the changes one can observe in the United States (see Figure 1.1). It should therefore be stated that the decreasing number of loyal voters is not only the characteristic of the British voting market, but also applies to other democratic states.

Analyzing the research on voting behaviors in different countries, Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg (1993) conclude that partisan ties are disappearing in most modern democracies. They are more and more often accompanied by people voting for a particular person, no matter what party he or she represents. A clear example illustrating these two trends is split-ticket voting, which is taking place more frequently as well. Split-tic...