- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Libraries and Learning Resource Centres

About this book

Libraries and Learning Resource Centres is a comprehensive reference text examining the changing role and design of library buildings. Critical evaluations of international case studies demonstrate the principles of library design.

Available for the first time in full colour, the second edition of the work focuses particularly on the important question of access and design in public libraries. Updated case studies and technical data allow the professional architect to use the book directly in planning library projects.

Providing guidance on balancing the needs of the collection and the user, Libraries and Learning Resource Centres will be of value to all professional architects involved in library planning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArquitecturaSubtopic

Arquitectura generalPart 1

History of the Library

1

History, Form and Evolution of the Library

How Libraries Evolved

The emergence of the library, as distinct from the museum or picture gallery, did not occur directly as a result of the invention of the printing press but as a consequence of the growth in rational thought. Most commentators note that the library as we know it first occurred in the Renaissance with the Biblioteca Malatestiana in Casena and Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence. The first from around 1450 and the second a century or so later were libraries rather than bookstores. Earlier notable libraries such as the one at Wells Cathedral and the Ptolemy Library in Alexandria (which contained perhaps half a million scrolls) were depositories of written material with only a casual distribution of reading space for scholars.

To be a library in the modern sense, there needs to be a collection of books, clear access to the study material and a well-designed arrangement of seats and tables for readers. This last requirement implies a satisfactory level of light, a functional plan with a logical structure of bookstore, bookshelves, study space and corridors, and a level of control over the use and management of the space. A library, therefore, is a controlled environment designed for the benefit of both book and reader. Against this criterion, the modern library emerged not in antiquity but on the back of the growth of European rationalist thought from the sixteenth century onwards.

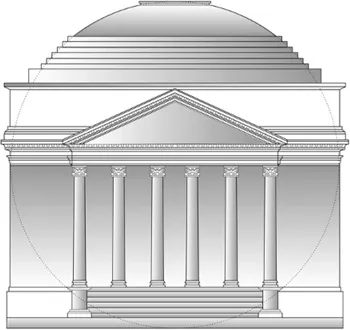

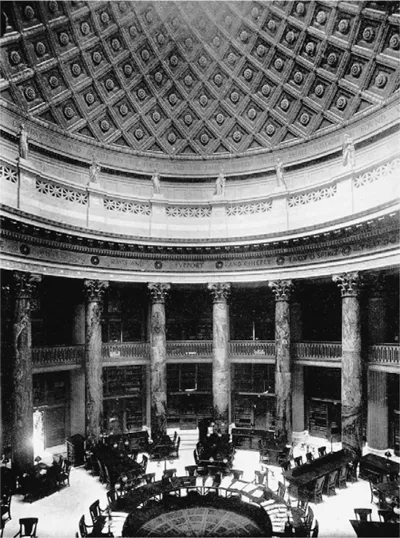

The great flowering of the library as a recognizable building type occurred in the eighteenth century. It was then that the library emerged with its own taxonomy of forms, functions and details. An early example is the Wolfenbüttel Library in Berlin (1710), with its elliptical reading room set symmetrically within a ‘golden section’ plan. This library also was one of the first free-standing libraries (as opposed to a library as a wing in a larger composition as in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, 1610). It had the authority of formal composition which marked the presence of the library in countless cities for two centuries. Dome and cube – the former as reading room, the latter as bookshelf accommodation – became the elemental architecture language for the library. The dome, usually surrounded by high-level windows formed in the circumference of the cylinder as it pierced the cube, allowed even light to filter down upon the reader. Those in the reading room could also (as in the former Reading Room at the British Museum in London) ponder upon their material within a volume designed for intellectual reflection.

The eighteenth century plan had a large area for book storage within a semi-basement. The position allowed books and journals to be delivered easily at road level, temperature and humidity could be controlled more readily than at high level and, by elevating the public to a first floor approach, the entrance could be grandly marked architecturally.

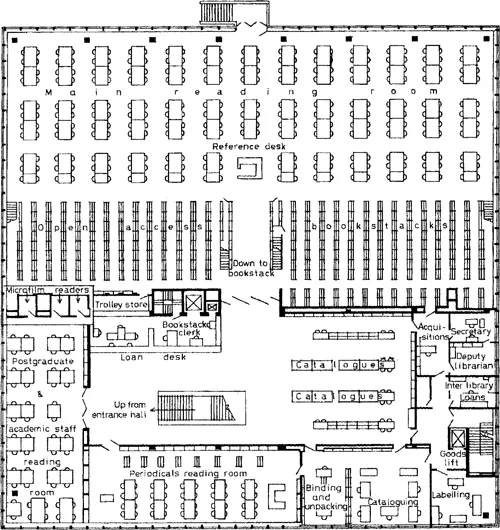

The plan, evolved and perfected through the eighteenth century, remained largely unaltered until the early twentieth century. A few changes occurred such as the introduction of cast-iron construction (notably at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, 1868), greater sophistication in the control of temperature and humidity (with early air-conditioning in some pioneering American libraries at the turn of the century) and improved security of the stock; but fundamental change had to wait until the 1930s. Then the old dependencies of plan and section were rejected – the modern library introduced fluid space for more fluid functions. The formal repertoire of recognizable forms, inside and out, gave way to new unfamiliar arrangements. The dominance of the reading room became eroded, the division between book storage on shelves and in store became less certain, and the library became more open and egalitarian in spirit. More recently, even the primary role of the book has been questioned. New technologies in the form of computer-based data and electronic images have changed the old assumptions again. As the library material becomes more freely available via information technology (IT), the library itself has begun to adapt to fresh arrangements of space and new inventions of form. Whereas it was once an exclusive and often private building type, over some 500 years the library has become a truly public building with genuine social space and community purpose.

Example of a dome and cube library at the University of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson, 1819. (Brian Edwards)

In some ways, the library’s fortune has followed closely that of the museum. Both building types share a common root and there was not much difference in the architectural arrangement between the Renaissance art gallery and that of the library. Both were long, evenly lit buildings with wall niches for books, sculpture or paintings. Often the library sat above the museum in a wing of a larger building. In both cases, the user stood or perched on a high seat as a spectator of the collection. Construction technology did not then allow for wide span buildings, so the column and wall bay became the unit of display. Sitting down did not occur in libraries until the sixteenth century and in museums until the nineteenth century.

The common root of library, art gallery and museum owes something to the nature of patronage. Art collecting and book collecting depended upon a sense of history; both were revised and made systematic by the Renaissance. Paintings, bronze statues and leather-bound hand-written books were trophies to be displayed. Collecting is the common basis of both library and museum buildings; use of the collection for study purposes tended to occur later. In some ways it was the growth in education in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries which split apart the library and museum as building types. Education certainly was behind the development of the library as an essential aid to higher learning. The book became less an object of treasure and more an object of use. It was this change in the status of the book, coupled with the expanding use of the printing press, which led to the removal of chains from many civic and university libraries.

Education too played a large part in forging the separation of the library from the cultural precinct of the museum and gallery. The formal repertoire of the library was developed in the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge and in the universities of Paris, Milan and Glasgow. The library, initially built as a wing in a college, matured in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century into a self-contained building. With physical separateness went architectural ambition; the library became a building to be viewed in the round. The Radcliffe Camera in Oxford by James Gibbs (1740) is a notable example. The museum, however, did not reach such heights of architectural distinctiveness for another century. Without the impetus of higher education to propel the building type forward, the museum stagnated architecturally. It remained a gallery-type building – a sequence of rooms leading to further rooms on a rather dull circuit. Where the circle interrupted the order of the rectangle, it was to form small sculpture courts (e.g. the National Gallery of Scotland, 1845). Without the impetus of the universities, and then of the civic authorities, the museum was not able to develop architecturally as fully as the library at least until the nineteenth century. When the museum did evolve architecturally, it was the correspondence between space and light which, like the library, led to innovation.

Reading Room, New York University, 1895, designed by McKim, Mead and White. (New York University)

Typical twentieth century library plan. Sheffield University Library, 1958, designed by Gollins, Melvin, Ward and Partners. (D. Insall and Partners)

In the library, the introduction of the central dome allowed daylight to penetrate to the interior. With the museum, the need to display works or walls without the glare of sunlight led to the introduction of large roof lights. This was an innovation which revolutionized the museum in the early nineteenth century, just as it had done to the library a century or more earlier. How differently libraries and galleries organize the relationship between space, study material and light is one key way in which the two building types can be distinguished. Even today with their different demands, it is the environmental servicing of space, as well as the collection, which fashions plan and section.

Libraries and the History of Space

Libraries are essentially collections of study material based upon the written, and increasingly electronic, word. Being collections, they are not unlike other depositories of human artefacts such as the museum and, in the need to display the material, they are not unlike art galleries. They are also similar to museums in their compact between the formal language of the container (in the shape of the building) and the nature of their contents. The integration of material and container allows the library to reflect higher ideals: the status of learning, the importance of the written word and the symbolic celebration of free access to society’s knowledge.

The correspondence between the book and the building flowed from the rational nature of thought in the Enlightenment. The library became a ‘safe, well-lit warehouse’ (Markus, 1993, p. 171) where the readers’ needs became as important as that of the collection. In the nineteenth century, and increasingly since, the text of the building and the text of the books within shared a common ideal. The formal organization of architectural space and the space in the mind liberated by the power of the written word became symbolically united. It is this symbiosis which led to the domed reading room – itself a metaphor for the human brain. The books, inventories, journals, maps and catalogues of the modern library are in this sense merely an enlarged version of the human intellect. Inevitably, the building sought simultaneously to both control the sum of human knowledge within its walls and to celebrate its presence.

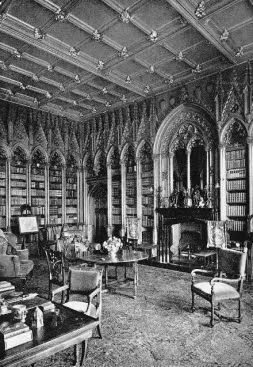

Library at Toddington Manor, Gloucester, designed by Sir Charles Barry in 1829. (Country Life)

It is not sufficient to see the library as a storehouse of knowledge, especially in the age of information technology. It is the delicate relationship between the books and architectural space which defines the library and helps us classify libraries into various categories – national, civic and academic. Reading and accessing knowledge via the computer screen requires a bond of dedicated effort between the book, reader, screen and space. The nature of the space varies according to the type of collection, the nature of the library and the ambition of the reader. Space is therefore essential, but the character of the space is not uniform. The social, cultural, political and educational aspirations of the library and its collection alter the type and the use of space.

In the library, a distinction needs to be drawn between private and semi-private reading. It is sometimes argued that private reading is an inappropriate activity in a public library (Roche, 1979). The library is a place of semi-private reading at best and it follows that total silence is an ideal that cuts across the nature of discourse which the modern library seeks to promote. The library is like a bank: there are the catalogues with details of customer accounts and secured areas with ready currency, but the main activity is at the interface between the customer, bank teller and bank note. The library too exists to encourage production at a similar interface and often the necessary human exchange is via the spoken word.

The University Library in California supports Berkeley’s intellectual vitality and innovative thinking in all departments, for both faculty and students.

The nature of space reflects the type of library, the activity in different functional zones and the needs of the reader working from book, journal or screen. Book and computer screen have quite different environmental needs. Reflected light on the screen impairs the ability to work effectively over a long period: sunlight on the book also creates eye strain (and can fade the printed page). Lighting levels for reading are not the same as for computer-accessed material, while ventilation sta...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 History of the Library

- Part 2 Planning the Library

- Part 3 Technical Issues

- Part 4 Library types

- Part 5 Speculations

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Libraries and Learning Resource Centres by Brian Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.