This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Religion and Society in Early Modern England is a thorough sourcebook covering interplay between religion, politics, society, and popular culture in the Tudor and Stuart periods.

It covers the crucial topics of the Reformation through narratives, reports, literary works, orthodox and unorthodox religious writing, institutional church documents, and parliamentary proceedings. Helpful introductions put each of the sources in context and make this an accessible student text.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Religion and Society in Early Modern England by David Cressy, Lori Anne Ferrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

II

THE ESTABLISHED CHURCH

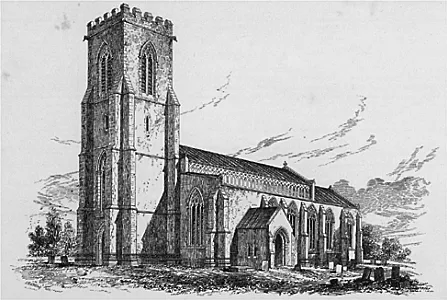

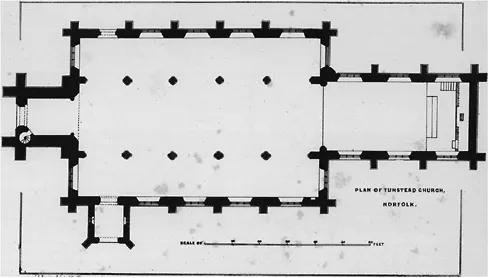

11 VIEW AND PLAN OF TUNSTEAD CHURCH, NORFOLK

The church was usually the largest and most substantial building in any parish. It dominated the community, both physically and spiritually. By the time of the reformation most English parish churches were already hundreds of years old. Parishioners adapted the space to changing liturgical needs. The church yard was consecrated ground, used for burials and also sometimes for recreation. The church porch, on the south side, served a variety of purposes, from meeting place to school-room, and weddings were performed there before the reformation. The tower held bells and served as a look-out, and also stored ladders, weapons, and fire-fighting equipment.

Inside the church parishioners assembled in the nave for weekly worship. Most sat on benches or stools, but wealthier parishioners paid for enclosed pews. Separate seating for men and women was common, and parishioners often arranged themselves by wealth and status. The eastern end of the church, called the chancel, belonged to the minister. Before the reformation the priest officiated before the east-end altar. Tudor Protestants replaced the stone altar with a moveable communion table, usually set longways in the chancel. Ceremonialists in the 1630s often enclosed this sanctuary with wooden rails, raised it with steps, and repositioned the table in the altar position. How parishioners conducted themselves during services, and where they sat or kneeled, were recurrent sources of controversy.

Every church had a stone font for baptisms, usually at the west end or near the south door. Preachers delivered sermons and read announcements from the pulpit, a raised and enclosed speaking platform most commonly on the north-east side of the nave. Many parishes also provided their minister with a reading desk for routine services. A locked parish chest held documents, registers, and money.

Source: Raphael and J. Arthur Brandon, Parish Churches: Being Perspective Views of English Ecclesiastical Structures (2 vols, 1851), vol. 2, illustrations facing pp. 15, 17.

Tunstead Church, Norfolk (exterior view)

Tunstead Church, Norfolk (plan)

12 THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER, 1559

Under Edward VI, Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer and other scholars transformed the Roman missal, breviary, graduale and ordinale into an English liturgy. The prayer book of 1549 was a cautiously reformed document, printed under the aegis of parliament and enforced by the first Act of Uniformity. A more radically Protestant prayer book followed in 1552, but was soon repealed by Queen Mary upon her accession. The Elizabethan prayer book of 1559 was essentially the version of 1552, with some notable exceptions that rendered it more conservative. The Book of Common Prayer familiarized generations of English worshippers to an idiosyncratic form of Protestantism that was reformed in doctrine but traditional in liturgy.

Source: William Keatinge Clay (ed.), Liturgical Services: Liturgies and Occasional Forms of Prayer Set Forth in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, Parker Society (Cambridge, 1868), pp. 33–8, 180–238; Joseph Ketley (ed.), ‘Black Rubric’ from The Two Liturgies, AD 1549, and AD 1552, Parker Society (Cambridge, 1864), p. 283.

Preface

There was never any thing by the wit of man so well devised, or so sure established, which in continuance of time hath not been corrupted, as (among other things) it may plainly appear by the common prayers in the church, commonly called divine service. The first original and ground whereof, if a man would search out by the ancient fathers, he shall find that the same was not ordained but of a good purpose and for a great advancement of godliness. For they so ordered the matter that all the whole Bible, or the greatest part thereof, should be read over once in the year, intending thereby that the clergy, and specially such as were ministers of the congregation, should, by often reading and meditation of God’s word, be stirred up to godliness themselves, and be more able to exhort other by wholesome doctrine, and to confute them that were adversaries to the truth. And further, that the people by daily hearing of holy scripture read in the church should continually profit more and more in the knowledge of God and be the more inflamed with the love of his true religion. But these many years past this godly and decent order of the ancient fathers hath been so altered, broken, and neglected by planting in uncertain stories, legends, responds, verses, vain repetitions, commemorations and synodals that commonly when any book of the Bible was begun, before three or four chapters were read out, all the rest are unread. And in this sort the book of Isaiah was begun in Advent and the book of Genesis in Septuagesima, but they were only begun and never read through. After a like sort were other books of Holy Scripture used. And moreover, whereas St Paul would have such language spoken to the people in the church as they might understand and have profit by hearing the same, the service in this Church of England these many years hath been read in Latin to the people, which they understood not, so that they have heard with their ears only, and their hearts, spirit, and mind have not been edified thereby. And furthermore, notwithstanding that the ancient fathers have divided the psalms into seven portions whereof every one was called a nocturn, now of late time a few of them have been daily said and oft repeated, and the rest utterly omitted. Moreover, the number and hardness of the rules called the pie and the manifold changings of the service was the cause that to turn the book only was so hard and intricate a matter that many times there was more business to find out what should be read than to read it when it was found out.

These inconveniences therefore considered, here is set forth such an order whereby the same shall be redressed. And for a readiness in this matter, here is drawn out a calendar for that purpose, which is plain and easy to be understanden, wherein, so much as may be, the reading of Holy Scriptures is so set forth that all things shall be done in order without breaking one piece thereof from another. For this cause be cut off anthems, responds, invitatories, and such like things as did break the continual course of the reading of the scripture. Yet because there is no remedy but that of necessity there must be some rules, therefore certain rules are here set forth, which as they be few in number so they be plain and easy to be understanden. So that here you have an order for prayer, as touching the reading of Holy Scripture, much agreeable to the mind and purpose of the old fathers, and a great deal more profitable and commodious than that which of late was used. It is more profitable because here are left out many things whereof some be untrue, some uncertain, some vain and superstitious, and is ordained nothing to be read but the very pure word of God, the Holy Scriptures, or that which is evidently grounded upon the same, and that in such a language and order as is most easy and plain for the understanding, both of the readers and hearers. It is also more commodious, both for the shortness thereof and for the plainness of the order, and for that the rules be few and easy. Furthermore, by this order the curates shall need none other books for their public service but this book and the Bible, by the means whereof the people shall not be at so great charge for books as in time past they have been.

And where heretofore there hath been great diversity in saying and singing in churches within this realm, some following Salisbury use, some Hereford use, some the use of Bangor, some of York, and some of Lincoln, now from henceforth all the whole realm shall have but one use. And if any would judge this way more painful because that all things must be read upon the book whereas before by the reason of so often repetition they could say many things by heart, if those men will weigh their labour with the profit and knowledge which daily they shall obtain by reading upon the book, they will not refuse the pain in consideration of the great profit that shall ensue thereof.

And for as much as nothing can almost be so plainly set forth but doubts may rise in the use and practicing of the same, to appease all such diversity (if any arise) and for the resolution of all doubts concerning the manner how to understand, do, and execute the things contained in this book, the parties that so doubt, or diversely take anything shall alway resort to the bishop of the diocese, who by his discretion shall take order for the quieting and appeasing of the same so that the same order be not contrary to anything contained in this book. And if the bishop of the diocese be in any doubt, then may he send for the resolution thereof unto the archbishop.

Though it be appointed in the afore written preface that all things shall be read and sung in the church in the English tongue, to the end that the congregation may be thereby edified, yet it is not meant but when men say morning and evening prayer privately, they may say the same in any language that they themselves do understand.

And all priests and deacons shall be bound to say daily the morning and evening prayer, either privately or openly, except they be letted by preaching, studying of divinity, or by some other urgent cause.

And the curate that ministereth in every parish church, or chapel, being at home and not being otherwise reasonably letted, shall say the same in the parish church or chapel where he ministereth and shall toll a bell thereto a convenient time before he begin, that such as be disposed may come to hear God’s word and to pray with him.

Of ceremonies, why some be abolished and some retained

The word ‘ceremonies’ refers to the liturgical practices (as distinguished from theological beliefs) outlined in The Book of Common Prayer. This section remained virtually unaltered from ...

Table of contents

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- I TRADITION AND CHANGE: THE OLD RELIGION AND THE NEW

- II THE ESTABLISHED CHURCH

- III RELIGIOUS CULTURE AND RELIGIOUS CONTEST IN ELIZABETHAN ENGLAND

- IV THE JACOBEAN CHURCH

- V CEREMONIALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS

- VI RELIGIOUS REVOLUTION

- CHRONOLOGY

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX