This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art History: The Basics

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Art History: The Basics is a concise and accessible introduction for the general reader and the undergraduate approaching the history of art for the first time at college or university.

It will give you answers to questions like:

- What is art and art history?

-

- What are the main methodologies used to understand art?

-

- How have ideas about form, sex and gender shaped representation?

-

- What connects art with psychoanalysis, semiotics and Marxism?

-

- How are globalization and postmodernism changing art and art history?

-

Each chapter introduces key ideas, issues and debates in art history, including information on relevant websites and image archives. Fully illustrated with an international range of artistic examples, Art History: The Basics also includes helpful subject summaries, further ideas for reading in each chapter, and a useful glossary for easy reference.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Art History: The Basics by Diana Newall, Grant Pooke, Diana Newall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ART THEORIES AND ART HISTORIES

WHAT IS ART AND WHAT IS ART HISTORY?

I’m delighted to have made an empty plinth that isn’t empty, where the exhibit itself is merely invisible.

(David Hensel 2006)

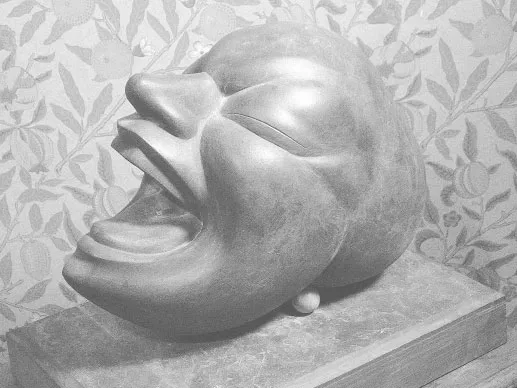

A British artist sends a sculpture to an internationally prestigious and open art exhibition. However, what the selectors actually accept for exhibition is not the jesmonite laughing head, but its slate plinth and bone-shaped wooden rest which had been accidentally separated from the sculpture during handling. The head, One Day Closer to Paradise, 2006 (Figure 1, p. 2), was duly returned to the bemused sculptor. The empty plinth (RA exhibit 1201), subsequently renamed Another Day Closer to Paradise (Figure 2, p. 3), was later auctioned with a donation made to charity. This is not an urban myth, but a widely publicised incident which occurred at the Royal Academy’s 2006 Summer Exhibition (Malvern 2006: 4–5). The artist involved, David Hensel (b. 1945), recalled:

the art world itself seems to be engaged in a cultural performance about our times, a parody about duplicity, marketing tactics, and acquiescence.

Figure 1 One Day Closer to Paradise, David Hensel, 2006, jesmonite, slate and boxwood base,44 × 33 × 22cm, © the artist.

Figure 2 Another Day Closer to Paradise, David Hensel, 2006, slate and boxwood, 44 × 33 × 22cm, © the artist.

Presenting this work in public and watching the reactions has produced many fascinating insights into how the arts work, about the need for understanding the broader picture of the dynamics of culture, and particularly the need to study the history of propaganda and patronage, the pursuit of invisible influence, in parallel to the study of a history of art.

(Letter from David Hensel, 1 December 2006)

Unsympathetic critics and commentators claimed that the treatment of Hensel’s RA submission demonstrated the ‘emperor’s new clothes’ syndrome, although the jury’s selection seemed to suggest just how arbitrary contemporary ideas about art and aesthetics seem to be.

Taking Hensel’s thoughts on his RA submission and its aftermath as a point of departure, we might reasonably ask what we actually mean by art and art history. These are the two central questions around which this primer has been written. This chapter will consider some of the changing ideas about art and its interpretation. What are the origins of art history as an academic discipline and how has it evolved? What is the purpose of art? And how might we characterise some of the developments of recent decades within the academic discipline of art history?

SO WHAT IS ART?

There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.

(Gombrich 1984: 4)

Gombrich’s Delphic observation suggests that art is something which artists do. The various examples used to illustrate this primer – ceramics, constructions, paintings, land art, installations, performance art, photomontage and sculpture – all have aesthetic status. In other words, the label ‘art’ connects very disparate objects, practices and processes.

Recognising this diversity, various categorisations have been made within definitions of visual art (including Fernie 1995: 326). Building on these we might propose a general set of guidelines for understanding what art is thought to be:

• Fine art has traditionally been used to distinguish arts promoted by the academy, including painting, drawing and sculpture, from craft-based arts. The latter typically refers to those works created for a function – such as ceramics, jewellery, textiles, needlework and glass which are still termed decorative arts. This distinction does not apply so strongly in contemporary art making where a wide variety of media are used including, for example, ceramics (Grayson Perry) and embroidery (Tracey Emin). There is, however, still a loose boundary between objects made with a specific function in mind (and therefore where technical and design-related concerns are paramount) and those which are made primarily for display.

• A broader definition of art encompasses those activities which produce works with aesthetic value, including film making, performance and architecture. For example, architecture has always had a close connection to painting, drawing and sculpture, two instances being the classical revival in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the Bauhaus aesthetic of the 1930s which frequently integrated fine art with design, craft and architecture.

• Contemporary definitions of art are not medium specific (as ideas around fine art tended to be) or particularly restrictive about the nature of aesthetic value (as Modernism was – see Chapter 2). These ideas are associated with the Institutional Theory of Art which is probably the most widely used definition. It recognises that art can be a term designated by the artist and by the institutions of the art world, rather than by any external process of validation. On the one hand it provides an expansive framework for understanding diverse art practices, but on the other, it is so broad as to be virtually meaningless. We will return to this in Chapter 7.

However, regardless of categorisation, all definitions of art are mediated through culture, history and language. To understand these differing concepts of art, we need to look at their social and cultural origin.

THE CLASSICAL CONCEPT OF ‘ART’

In a Western context, art understood as a practical, craft-based activity has the longest history. For example, within ancient Greek culture there was no word or concept approximating to our understanding of ‘art’ or ‘artist’. However, the Greek word ‘techne’ denoted a skill or craft and ‘technites’ a craftsman who made objects for particular purposes and occasions (Sörbom 2002: 24). Similarly, within the classical world, examples of craft, such as statues and mosaics, had practical, public and ceremonial roles. The classical sculpture of Zeus, copy after a fifth-century BCE original (Figure 3, p. 7), would have been judged according to the technical standard demonstrated, and by the extent to which it fulfilled the social and civic roles expected of craft. Foremost of these was the belief that the human form should be represented in its most life-like and vital sense as the union of body and soul (Sörbom 2002: 26). The idea that a sculpture or mosaic should be judged on criteria independent of such purposes was alien to the classical concept of craft.

CE and BCE

In response to concerns over the implied Christian bias of BC (before Christ) and AD (anno domini – in the year of our Lord), contemporary scholars sometimes use CE (common era, equivalent to AD) and BCE (before the common era, equivalent to BC) instead.

Within a Western tradition of art, originating from Greek and Roman practice, the categories of art and craft have become familiar within specific contexts, cultures and in relation to particular audiences. Throughout Europe and North America for example, cultural assumptions about what art customarily was were closely linked to the origins and development of the academic subject of art history itself. Of central importance to this were the social institutions such as academies and museums which were established from the late sixteenth century onwards. Collectively, these interests, and those associated with them, established normative definitions of art, that is, ideas about how art should look and what it should do, variations of which have continued today.

Another point worth making is that to label something as art implies some kind of evaluative judgement about the image, object or process. That is, it recognises the specificity of a range of practices within a broader category or tradition with particular claims to aesthetic and/or social value. But it is important to understand that the meaning and attributions of art are particular to different contexts, societies and periods. Whatever the prevalence through time of objects and practices with aesthetic purpose, ideas and definitions of art are neither timeless nor beyond history, but relate to the social and cultural assumptions of the societies and environments which fashion them.

Figure 3 Zeus, copy after a fifth-century BCE original, marble, Louvre, Paris, © photograph Ann Compton, photograph Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

FINE ART AS AN EXCLUSIVE CATEGORY

The academy-based categorisation of fine art and the consensus which underpinned it for several centuries demonstrate how durable and hegemonic such interests were. But from the later nineteenth century onwards many avant-garde artists began to make work which questioned either the conventional subject matter and primacy of these distinct categories (history paintings and portraiture for example), or the tradition of representation which they signified. For example, the work of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) underlined the importance of still-life as a genre to the birth of modernism (Bryson 1990: 81–86). Similarly, the development of collage by Braque and Picasso, and their inclusion of everyday objects such as flyers and tickets, explored the actuality of the flat surface, rather than concealing it through illusionism which had been such a dominant feature of academy-sponsored painting and sculpture.

Academy-based ideas typically marginalised non-Western art practices which reflected different ideas about aesthetics, culture and meaning. Overseas trade, colonisation and imperialism stimulated interest in tribal masks, carvings, fabrics and fetish objects from regions such as Africa, Asia, India and Iberia. These objects, and the indigenous cultures they represented, contributed to major ethnographic collections throughout Europe, stimulating widespread interest in non-Western art and artefacts (Ratnam 2004a: 158–60). Within the avant-garde, various artists like Braque, André Derain (1880–1954), Ernst Kirchner (1880–1938), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Picasso and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958) popularised the cult of primitivism. Whilst such interests frequently reflected romanticised stereotypes about what primitive art and culture actually signified, there was also recognition of the social and political dimensions to such use (Leighten 1990: 609–30).

The legacy of academy-based conventions of art making is such that there is still a tendency by some to rate fine art – painting, drawing and sculpture – as intrinsically superior to installation, performance or conceptual art practices. For example, the sponsoring of a ‘Not the Turner Prize’ by a national newspaper demonstrates the willingness within parts of the media industry to tap into palpable unease among sections of the general public about the criteria for what is admissible as art and the cultural authority of those who customarily make such judgements. Similarly, the press and public furore over the example of the empty plinth, cited at the start of this chapter, suggests just how deep-seated some of these ideas actually are. In order to understand such categorisations and exclusions, it is useful to consider those aesthetic theories which have been historically influential in shaping values and assumptions about the meaning of art.

ART AS IMITATION

Consider Adam and Eve, 1526 (Figure 20, p. 142), by Lucas Cranach I (1472–1553), and John Singer Sargent’s (1856–1925) portrait of Mrs Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel, 1903 (Figure 21, p. 145). There are appreciable differences between these two paintings in terms of subject, date, genre, origin, materials and meaning. Whereas Cranach attempts to convey the symbolism of a Biblical story (the Temptation of Adam), and Sargent seeks to capture the likeness of his sitter, both paintings work on the basis of resemblance – either the circumstances of an imagined event or the features of a particular individual.

The theory of imitation (or mimesis), situates art as a mirror to nature and the world around us. Within the history of Western painting, the principle of imitation was associated with the invention and widespread adoption of single point perspective, an innovation which, literally and symbolically, underlined the primacy of the artist’s viewpoint. This was a major breakthrough which assisted in ever more convincing illusions of depth and space on a flat surface. For example, a naturalistic painting, like Masaccio’s Holy Trinity, 1427–28, in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, became, in effect, a hole in the wall to another spatial dimension. This example was emblematic of attempts to capture the way things looked, or were believed to be. The success of an art work became, in large part, dependent on the extent and ease with which spectators were seduced into suspending disbelief, forgetting that they were in fact looking at a flat, two-dimensional surface.

Artchive online

Art works are referenced throughout this book. Although many have been included as illustrations, the reader is encouraged to use the internet to view other works and artists referenced or discussed. One useful source, in addition to the major gallery websites, is the Artchive website: http://artchive.com/ftp_site.htm

For example, select Masaccio from the list of artists, view the image list and select Trinity (1427–28) to view this work.

PLATO’S IDEA OF MIMESIS

The idea of art as imitation can be traced back to book ten of Plato’s The Republic, c.340 BCE (Sheppard 1987: 5–9). Here, Plato dismissed painting, which he understood in terms of mimesis or imitation, as having limited use. A painting of a table was neither the ideal form of the table (the perfect idea of a table which existed in divine imagination) nor the table made in a carpenter’s workshop. According to Plato, a painting ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Art theories and art histories

- 2 Formalism, Modernism and modernity

- 3 A world still to win: Marxism, art and art history

- 4 Semiotics and poststructuralism

- 5 Psychoanalysis, art and the hidden self

- 6 Sex and sexualities: representations of gender

- 7 Exploring postmodernities

- 8 Globalised proximities and perspectives

- Art and art history: website resources

- Glossary of terms

- Bibliography

- Index