CHAPTER 1

(Not) your everyday public space

Jeffrey Hou

With a sixteen-foot statue of Vladimir Lenin standing in a street corner, a salvaged rocket sitting on top of a building, a car-eating troll crawling under a bridge, Fremont is undoubtedly one of the most eccentric neighborhoods in Seattle. One day in 2001, the neighborhood (a.k.a. the Center of the Universe) welcomed yet another addition to its treasured collection – an eight-foot-long metal pig that was anonymously planted on a sidewalk overnight.

The pig became an instant celebrity. Neighbors wondered who left it there. The local press followed the news for months – trying to identify the instigator(s), how the pig was erected without permission, and then why it mysteriously vanished two months later, just one day before it was to be moved to a new location following complaints by several business owners. It turned out that the pig was the work of two anonymous artists. The artwork was meant as an anti-consumerism statement, mocking the official “Pigs on Parade,” an art and fundraising event that featured decorated pig sculptures in malls and streets of Seattle.

Planted on a public sidewalk, Fremont’s pig was not only a social and artistic statement, but also an attack on the official public sphere in the contemporary city. Although the pig did not physically alter the space except for its footprints, its unauthorized presence challenged the norms of public space by defying the city’s requirement for a deposit to put art on a sidewalk. Although its actual production did not involve the so-called public process, the work engaged the public through the media and everyday conversation. Through the space it occupied and the debates it engendered among neighbors, citizens, and the media, the pig renewed the discursive instrumentality of public space as a forum for open discussion. It gives meanings to the full notion of publicity in a public space.

In cities around the world, acts such as the pig installation in Fremont represent small yet persistent challenges against the increasingly regulated, privatized, and diminishing forms of public space. In Portland, Oregon, activists from the group City Repair painted street intersections in bright colors and patterns, and involved neighbors in converting them into neighborhood gathering places. In Taipei, citizens frustrated with rocketing housing costs staged a “sleep-in” in the streets of the most expensive district in the city to protest the government inaction. In London, Space Hijackers, a group of self-proclaimed “anarchitects,” has performed numerous acts of “space hijacking,” from “Guerrilla Benching” – installing benches in empty public space – to the “Circle Line Party” in London’s Underground (till they were stopped by the police).

Rather than isolated instances, these acts of insurgency transcend geographic boundaries and reflect the respective social settings and issues. In cities from Europe to Asia, residual urban sites and industrial lands have been occupied and converted into new uses by citizens and communities. From coast to coast in North America, urban and suburban landscapes have been adapted and transformed by new immigrant groups to support new functions and activities. In Japan, suburban private homes have been transformed into “third places” for community activities.1 From Seattle to Shanghai, citizen actions ranging from gardening to dancing have permanently and temporarily taken over existing urban sites and injected them with new functions and meanings.

These instances of self-made urban spaces, reclaimed and appropriated sites, temporary events, and flash mobs, as well as informal gathering places created by predominantly marginalized communities, have provided new expressions of the collective realms in the contemporary city. No longer confined to the archetypal categories of neighborhood parks, public plaza, and civic architecture, these insurgent public spaces challenge the conventional, codified notion of public and the making of space.

What can we learn from these acts of everyday and not-so-everyday resistance? What do they reveal about the limitations and possibilities of public realm in our contemporary city? How do these instances of insurgency challenge the conventional understanding and making of public space? How are these spaces and activities redefining and expanding the roles, functions, and meanings of the public and the production of space? These are the questions we intend to address in this book.

Public space: democracy, exclusion, and political control

Public space has been an important facet of cities and urban culture. In cities around the world, urban spaces such as plazas, markets, streets, temples, and urban parks have long been the centers of civic life for urban dwellers. They provide opportunities for gathering, socializing, recreation, festivals, as well as protests and demonstrations. As parks and plazas, urban open spaces provide relief from dense urban districts and structured everyday life. As civic architecture, they become collective expressions of a city as well as depositories of personal memories. As places where important historical events tend to unfold, public spaces are imbued with important, collective meanings – both official and unofficial.

Serving as a vehicle of social relationships, public discourses, and political expressions, public space is not only a physical boundary and material setting. Henaff and Strong (2001: 35) note that public space “designates an ensemble of social connections, political institutions, and judicial practices.” Brill (1989: 8) writes that public space comes to represent the public sphere and public life, “a forum, a group action, school for social learning, and common ground.” In the Western tradition, public space has had a positive connotation that evokes the practice of democracy, openness, and publicity of debate since the time of the Greek agora. Henaff and Strong (2001) further argue that the very idea of democracy is inseparable from that of public space. “Public space means simultaneously: open to all, well known by all, and acknowledged by all. … It stands in opposition to private space of special interests” (Henaff and Strong 2001: 35). Landscape architecture scholar Mark Francis (1989: 149) writes, “Public space is the common ground where civility and our collective sense of what may be called ‘publicness’ are developed and expressed.” Fraser (1990) argues that, as a public sphere, public space is an arena of citizen discourse and association. Furthermore, I. M. Young (2002) sees public space in a city as accessible to everyone and thus reflecting and embodying the diversity in the city.

However, contrary to the rhetoric of openness and inclusiveness, the actual making and practice of public space often reflect a different political reality and social biases. Agacinski (2001: 133) notes that, before the French Revolution, “the public” in the Western tradition referred to the “literate and educated” and “was never thought to be the same as the people.” Even in recent Western history, some have argued that, “despite the rhetoric of publicity and accessibility,” the official public sphere rests on a number of significant exclusions, based on gender, class, and race (Fraser 1990: 59). The gender division of public and private, in particular, has been a powerful instrument of exclusion as it relegates women to the private sphere and prevents them from fully participating in the public realm (Drucker and Gumpert 1997). By delineating what constitutes public and private and by designating membership to specific social groups, the official public space has long been exclusionary, contrary to Young’s (2002) notion of a public space that embodies differences and diversity.

Aside from the practice of exclusion, public space has also been both an expression of power and a subject of political control. Under medieval monarchy in the West, public space was where political power was staged, displayed, and legitimized (Henaff and Strong 2001). In the totalitarian societies of recent times, large public spaces serve as military parade grounds – a raw display of power to impress citizens as well as enemies. In modern democracies, as the power has shifted to the people, public spaces have at last provided a legitimate space for protests and demonstrations – an expression of the freedom of speech. But such freedom has never come without considerable struggles and vigilance. In the post-9/11 world of hyper-security and surveillance, new forms of control in public space have curtailed freedom of movement and expression and greatly limited the activities and meanings of contemporary public space (see Low and Smith 2005).

Across the different cultural traditions, the functions and meanings of public space have varied significantly, illustrating the varying means and degrees of social and political control. In recent Western democracies, public space and the formation of public opinion have been important components of the democratic process. Through opportunities of assembly and public discourses, political expressions in the public space are important in holding the state accountable to its citizens. This distinction between the public and the state has been an important ingredient in democratic politics. By contrast, in countries influenced by Confucianism in the East, social and individual life is dictated predominantly by obligations to state and family, with little in between. The official public space is traditionally either non-existent or tightly controlled by the state.

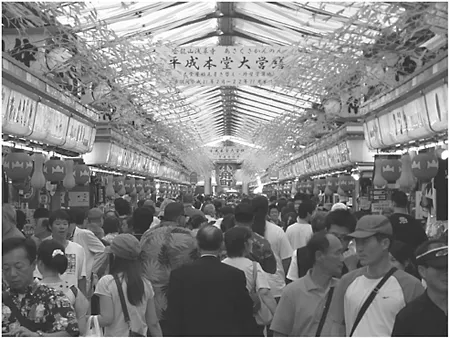

A useful illustration is Edo-era Tokyo. Under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, the city was spatially divided between Yamanote (consisting of large private estates occupied by ranking officials in the upland) and Shitamachi (the compact and tightly regulated quarters for the commoners in the flatland). In Shitamachi, gated streets and waterfront markets served as the only recognizable form of public gathering space. To escape from the gated quarters and regimented pattern of everyday life, one had to go to the pleasure grounds that lay outside the official quarters of the city (Figure 1.1).

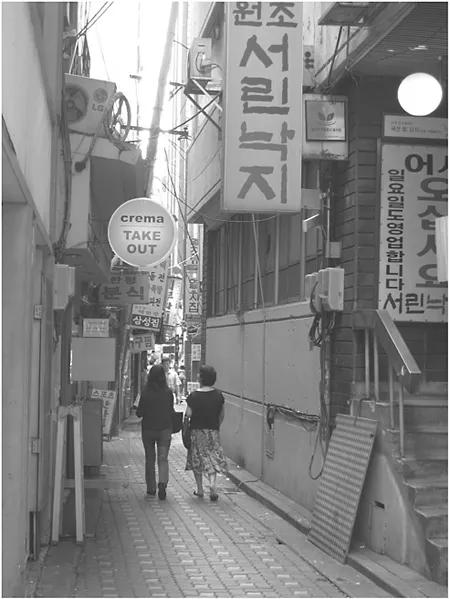

In many Asian cities, public space has been synonymous with spaces that are representing and controlled by the state. In contrast, the everyday and more vibrant urban life tends to occur in the back streets and alleyways, away from the official public domain. Seoul’s Pimagol (’Avoid-Horse-Street’), narrow alleys that parallel the city’s historic main road Jong-ro, serve as an example (Figure 1.2). To avoid repeatedly bowing to the noble-class people riding on horses on Jong-ro, a requirement back in the days of feudal power, the commoners turned to the back alleys, away from the main road. Over time, restaurants and shops began to occupy the back alleys, which became a parallel universe and an important part of the vibrant everyday life in the city.

The development and design of public parks in America provides yet another illustration, showing how public space has long been an ideologically biased and regulated enterprise contrary to the rhetoric of openness. In the United States, Cranz (1982: 3, 5) argues that early parks were built from “an anti-urban ideal that dwelt on the traditional prescription for relief from the evils of the city—to the country.” The emergence of reform parks in the United States further demonstrated this bias. Located in mostly dense, immigrant and working class neighborhoods, they were designed to move children and adults from the streets (Cranz 1982). With the goal of social and cultural integration, and provisions for organized play, the parks and

palygrounds were also designed to assimilate immigrants into the mainstream American culture (Cranz 1982). Today, although multiculturalism is more widely acknowledged, the historic bias continues, as Low, Taplin, and Scheld (2005: 4) found that “restrictive management of large parks has created an increasingly inhospitable environment for immigrants, local ethnic groups, ...