1

TRENDS IN ECONOMIC SANCTIONS POLICY: Challenges to conventional wisdom

Kimberly Ann Elliott

According to the conventional wisdom, one consequence of the more complex, less ordered environment following the end of the Cold War was a proliferation of US economic sanctions in response to demands to “do something,” about ethnic conflict, human rights violations, drug trafficking, terrorism, or nuclear proliferation. In this conventional wisdom, US sanctions policy also became more unilateral, with Congress in the driver’s seat and ethnic and other special interests doing the navigating. Evidence collected for the third edition of Economic Sanctions Reconsidered suggests that the conventional wisdom, while not entirely wrong, misses some important nuances.1

The frequency of US sanctions increased in the 1990s, but not as much as many people think, if a longer view is taken, and US sanctions have not been nearly as unilateral as in the past. Moreover, there was far more activity by the European Union than is generally recognized, often in cooperation with the United States but sometimes not. Also contrary to the conventional wisdom, Congress does not appear to have intervened more often than before, but the nature of that intervention has changed in important ways. Finally, the really big changes in sanctions policy have been in the United Nations (UN), not in the United States. The collapse of the Soviet Union freed the UN from its Cold War straitjacket and allowed it to intervene more aggressively in international affairs, including the imposition of mandatory economic sanctions ten times compared to just twice prior to 1990.

At the same time, the international economy has become increasingly integrated over the past two decades, with international trade and capital flows outpacing global output. This is a double-edged sword for economic sanctions, since interdependence increases potential vulnerability to disruption of these flows while also increasing the opportunities for evasion. These trends suggest that unilateral sanctions should become less effective, all else equal, and multilateral measures more effective. But the mechanisms for translating “economic pain into political gain” are still not well understood. The backlash against the humanitarian consequences of the broad UN sanctions against Iraq and Haiti resulted in a search for “smart” or targeted sanctions that dominated UN discussions of the sanctions tool into the new century.

Proliferation of economic sanctions in context

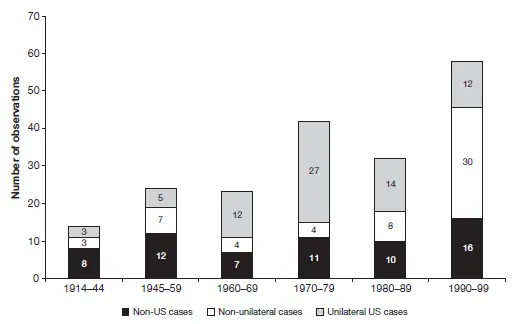

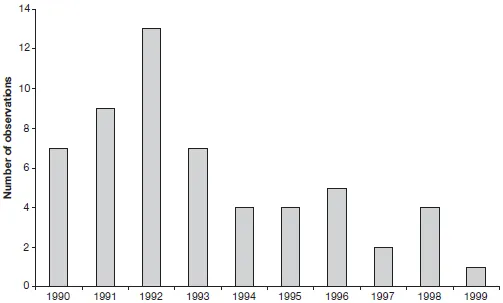

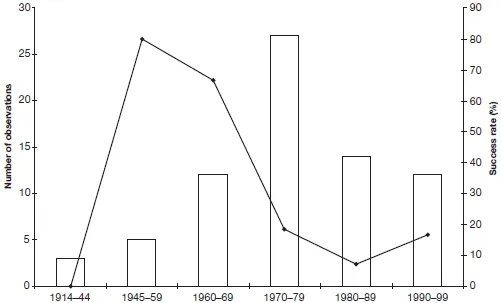

Figure 1.1 gives a snapshot of foreign policy sanctions launched in the twentieth century. Our study does not cover normal commercial reprisals, and our coverage probably misses several cases between countries of the second and third rank. That said, we have recorded 193 episodes, starting with World War I and extending through the UN sanctions against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in 1999.2 Nearly 60 new instances of sanctions were recorded in the 1990s and, of these, 42 involved the United States, usually in cooperation with other countries.3 Contrary to conventional wisdom, less than a third of the cases involving the United States were unilateral initiatives. To be sure, several high profile cases launched in the 1990s (such as the sanctions against India and Pakistan over their nuclear weapons tests), as well as a few inherited from the past (notably Cuba, Libya, and Iran) were unilateral endeavors. But in episode-count terms, the United States was less a Lone Ranger in the 1990s than in the 1970s and 1980s. It is also notable that, while the number of new sanctions imposed nearly doubled in the 1990s compared to the 1980s, the increase is less dramatic when compared to the previous 1970s peak. Moreover, Figure 1.2 shows that the proliferation of cases slowed markedly after the first part of the decade.

Table 1.1 shows the changes in the distribution of sanctions users in the 1990s, as well as the changing geography of those most likely to be targeted with economic sanctions. It shows clearly the relative decline of the United States as a user of sanctions (though it remains at the top in absolute terms), as well as the sharply increased sanctions activity by the European Union, Russia, and the United Nations. It must be noted, however, that several of the UN sanctions are weakly enforced arms embargoes, designed to curtail civil strife and genocide, and most European sanctions involve relatively minor aid cutoffs.

The targets of choice have also changed in the 1990s, reflecting in various ways the end of the Cold War. The Soviet Union or its allies were targets of Western sanctions (mainly US-led) nine times in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, Western sanctions against the Former Soviet Union (FSU) sharply diminished, but the new FSU states were subject to six sanctions initiatives by Russia in attempts to induce more favorable economic or political terms from its newly independent neighbors (using our definition of a foreign policy sanction).4 The other striking changes are the decline in new cases targeting Latin American countries and the rise in new cases targeting African countries. In broad terms, this reflects the swing of Latin America to democratic governance and the rising incidence of civil strife, despotic leadership, and large-scale killing in Africa. This shift in locus – from the US backyard to the European backyard – appears to be one factor in the decline in unilateral US sanctions and the rise in European initiatives.

Figure 1.1 Trends in the use of economic sanctions

Figure 1.2 Sanctions trends in the 1990s

Table 1.1 Senders and targets in sanctions cases initiated 1970–99

Congress and the role of domestic politics in US sanctions policy5

Another piece of the conventional wisdom about economic sanctions in the 1990s is that the US Congress became much more involved in imposing sanctions. This trend purportedly reflects a relaxation of national security constraints with the end of the Cold War and an increased role for domestic political motives. A careful analysis of US sanctions cases over time, however, suggests that the role of Congress in sanctions policy began changing well before the Cold War ended and that détente and other political and institutional changes in the US government were nearly as important as the collapse of the Soviet Union.6

In the 1970s (and 1980s), Congress was quite active on foreign policy issues, but it intervened in relatively limited fashion, passing laws to encourage the executive to impose sanctions in pursuit of Congress’s goals, but not mandating it, or restricting economic or military aid, often for relatively short periods of time. Perhaps the most striking change between the 1970s and 1990s is the increase in country-specific sanctions legislation and the related increase in presidential sanctions intended to head off more severe, or less flexible, congressional action. The hand of narrow special interest groups (not necessarily ethnically based) is also more apparent in many of these cases than in earlier periods. There were just two country-specific congressional sanctions actions in the 1970s (the boycott of Ugandan goods) and 1980s (the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act against South Africa). There were five in the 1990s: new sanctions against Burma (investment and aid bans that were extended in 2003 to include a ban on all imports) and Romania (denial of most favored nation (MFN) status), and the expansion of sanctions against Cuba, Iran, and Libya.

Whether or not they served the national interest, the Helms-Burton bill targeting Cuba and the Iran–Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) were both strongly influenced by special interest lobbying – the American Israel Political Action Committee in the case of Iran, the families of the Pan Am bombing victims in the case of Libya, and the Cuban-American community with respect to Helms-Burton. These bills also brought American policy to a new level of unilateralism by threatening sanctions against firms in third countries that do not cooperate with US sanctions against the primary target – even though their home governments have imposed no such sanctions against Iran, Libya, or Cuba. A similar bill, pushed by African-American groups concerned about slavery and religious groups concerned about persecution of Christians in Sudan’s civil war, would have barred companies investing in Sudan’s petroleum industry from issuing securities on US financial markets. It passed the House of Representatives overwhelmingly in early 2001 and was put aside only when Sudan offered to cooperate in the war on terrorism after the September 11 attacks. Nevertheless, the public pressure has caused some western oil companies to disinvest in Sudan, though they have been replaced by companies primarily from India and Malaysia.7

In addition, the lifting of some sanctions against Sudan, Pakistan, and Azerbaijan suggests that the war on terrorism could help to break the political logjam that has kept some sanctions in place for decades with no discernible benefit for US interests. More generally, it might induce the Congress to grant more flexibility and discretion to the executive branch in the conduct of foreign policy. As of early 2003, however, the relative bipartisanship that initially surrounded the war on terrorism began to fray amid concerns over the war in Iraq and the Bush administration’s embrace of a preventive, rather than pre-emptive, war policy for protecting American interests. Still, amid international and domestic debates over how quickly political control should be turned over to the Iraqi people, the American takeover of Iraq did result in an end to the much-criticized UN embargo against that country (except for continuing controls on military goods and the seizure of Saddam Hussein’s personal assets).

Sanctions effectiveness in the 1990s

Preliminary findings from the data collected for the third edition of Economic Sanctions Reconsidered suggest that, in terms of achieving their foreign policy objectives, sanctions in the 1990s were about as successful (or unsuccessful, depending on your perspective) as those imposed over the previous two decades. Our success scale has two components, both judgmental: was the objective achieved, at least in part? How much did the sanctions contribute to a positive outcome? By this scale, sanctions contributed to positive foreign policy outcomes (from the perspective of the sender government) 31 percent of the time, identical to the success rate in the 1970s and a slight recovery from the trough of the 1980s (Table 1.2).8

Table 1.2 Use and effectiveness of economic sanctions as a foreign policy tool

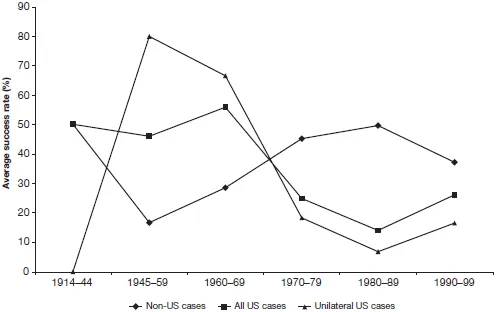

As in the second edition, the United States continued to perform more poorly with its sanctions policy than other senders, particularly when it acted unilaterally. As shown in Table 1.2, US unilateral sanctions succeeded in only 17 percent of cases in the 1990s and in only 15 percent for the entire 30-year period 1970–99. The latter is barely half the success rate for all cases of sanctions in this period and just a third of the 44 percent success rate for all other senders (calculated from figures in the Table; see Figure 1.3). The lack of a correlation between frequency of use and foreign policy effectiveness is one of the factors many observers point to in asserting that domestic politics must be driving US sanctions policy (Figure 1.4). The discussion above suggests that, while these critics may have a point, domestic politics is hardly the only factor in US sanctions policy.

Figure 1.3 Effectiveness of foreign policy sanctions, 1914–99

Figure 1.4 Use and effectiveness of unilateral US sanctions

The United Nations enters the sanctions scene

The end of the Cold War dramatically increased the latitude available to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) when confronted with international threats to collective peace and security. That, combined with an evolving and expanding definition of collective peace and security, led the UNSC to become far more active in imposing economic sanctions than in the previous 45 years. After the initial burst of enthusiasm, however, disillusionment quickly set in. The embargo of Iraq dragged on for more than a decade, reducing living standards to levels not seen for decades, and the economic embargo of Haiti, one of the poorest countries on the earth, led hundreds of desperate refugees to risk their lives in attempts to flee to the United States. Moreover, the threat or use of military force was necessary in both cases to achieve the initial goals – reversing the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and restoring the democratically elected government in Haiti. Comprehensive economic sanctions against Yugoslavia seem to have contributed to the peace settlement in Bosnia, but, again, at very high costs to the civilian population.

Thus, in these early cases, the economic and humanitarian pain inflicted by broad multilateral sanctions often seemed to outweigh the political gain. Over the course of the 1990s, the UN maintained a relatively higher level of sanctions activity than during the Cold War, but the nature of that activity has changed sharply – away from the comprehensive embargoes of the early decade to more limited measures:

- arms embargoes against Somalia and Rwanda; and

- arms embargoes plus travel restrictions and limited assets freezes against Afghanistan, Liberia, Libya, the UNITA faction in Angola, and the rebels in Sierra Leone.

Other than arms, the only restrictions on trade were limited restrictions on strategic commodities–lucrative diamond exports from rebel-held areas of Angola and Sierra Leone, respectively (as well as transshipments through Liberia in the latter case), an oil embargo against Sierra Leone for a short period when the rebels controlled the capital, and, in mid-2003, restrictions on timber exports from Liberia to deny the Taylor government revenues that might be used to fuel the renewed civil conflict there.

These sanctions have not been particularly effective. The civil war in Angola ended only after rebel leader Jonas Savimbi was killed and those in Sierra Leone and Liberia were disrupted by external military intervention. The only case with some degree of success was Libya but in that case, targeted UN sanctions were buttressed by comprehensive US sanctions and, still, it took years to gain the surrender for trial of the suspects in the Pan Am bombing case.

Nevertheless, continuing ethnic conflicts in the Balkans, Africa, and elsewhere, as well as the new war on terrorism, continue to generate interest in improving economic sanctions as a tool to promote international peace and security. In addition to looking for ways to ameliorate the costs of sanctions for innocent civilians and third parties, those interested in making multilateral sanctions more effective are questioning whether the UN has sufficient resources, authority, or expertise to monitor and enforce multilateral sanctions. Many in the UN and academic communities are also analyzing whether targeted sanctions such as those used in Africa and Afghanistan, in particular freezing the personal assets of political, military, and economic leaders in rogue states, can be made more effective.9

Risi...