![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Distance Education—Successes and Failures

Civilization is in a race between education and catastrophe.

(H. G. Wells)

Online and distance education is very likely the fastest growing area of education in the world today, in both the developed and developing worlds. And, while the origins of this growth are fairly recent, the roots of distance education go back a long way. Some authors date its beginnings to the invention of the “Penny Post” (the ability to send a letter anywhere in the U.K. for one old penny) and Isaac Pitman's resulting correspondence course in shorthand.

But there are counterclaims from other countries, notably Australia and the United States, and other authors suggest that St. Paul's epistles represent a very early form of open and distance education, with distance text in the form of letters and face-to-face support in the form of sermons. My own belief is that there is a case to be made for the Ten Commandments as the first distance learning text, delivered, as it happened, by tablets—of stone, rather than the later electronic form …

Whatever the arguments about its origins, there can be little doubt that there are now large numbers of distance institutions at every level worldwide, many of them very large—the Open University of China, with around 2.7 million students; the Indira Gandhi National Open University in India, with more than 3 million students; Anadolu University in Turkey, with 1.7 million students; the University of South Africa, with 300,000 students; the Open University in the U.K., with 250,000 students; and so on.

Some of these institutions now have a global reach, with students in many places apart from their home countries—for example, one of the oldest distance education providers, the University of London International Programme, founded in 1858, has 50,000 students studying in 190 countries and has five Nobel Laureates amongst its alumni, including Nelson Mandela. And the arrival of e-learning means that international competition between institutions will only go on increasing. Private institutions are being set up—corporate universities such as the “Coca-Cola University” are the fastest growing sector of higher education in the United States, for example, and countries that were previously net importers of education, such as Malaysia and—very significantly—China, are now moving towards becoming exporters of education.

There are many reasons for the success of distance education, three of the most important being costs, sustainability and access.

Costs and Benefits of Distance Education

The subject of costs and benefits of distance education will be examined in more detail in Chapter 11. But there can be little doubt that distance education is considerably cheaper for governments, institutions and students.

For Governments

Those governments that subsidize higher education in some way, either through grants to institutions or through grants and loans to students, not only benefit from the intrinsically lower costs of distance education, but also from the fact that distance students are also often economically active while studying—in other words, they are contributing to society through their contribution to Gross National Product and most directly through their taxes.

For Students

The main cost of a university degree to full-time, face-to-face students is not the tuition fees they pay, but the loss of earnings they experience while studying. Since in many cases distance students pay lower fees and can continue to earn, the cost of their degree is much less (see Chapter 11).

For Institutions

The cost of providing distance education to the institutions themselves will depend on whether they are “single-mode,” only offering distance education, or “dual-mode,” offering both face-to-face and distance education. Costs in a single-mode institution will be somewhat arbitrary depending on their financial structures, but Rumble (1992) has shown that a dual-mode institution will always be able to provide its distance education provision at a lower cost than is likely to be achieved by a single-mode institution, partly through synergy with its full-time provision. This suggests that distance education is generally less expensive to institutions than conventional education and partly explains the immense growth in distance education programs in recent years as institutions reach out for new customers.

Sustainability of Distance Education

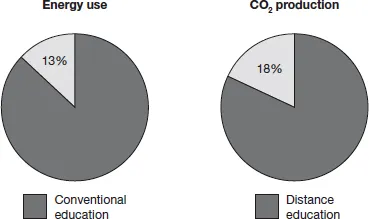

In a time of global austerity and global warming, issues of sustainability become increasingly important. Roy, Potter and Yarrow (2007) have suggested that distance education is far more sustainable than conventional education, both in energy (13% of conventional education use) and in carbon dioxide (CO2) production (18% of conventional educational use)—see Figure 1.1.

These sustainability advantages arise from savings on things like estate maintenance, which is obviously much smaller for a distance university without any students present on campus. (It is interesting to note that, in a later paper, Roy concludes that e-learning is not more sustainable than standard correspondence education despite the apparent savings on paper and postage. Rumble [2004] and Hulsmann [2000] come to similar conclusions about the comparative costs of e-learning versus conventional distance education. I shall return to this issue in Chapters 8 and 11.)

Figure 1.1 Sustainability of conventional education and distance education compared (Roy, Potter and Yarrow 2007)

Such an advantage in sustainability can only be an advantage to distance education over conventional education, as the costs of energy and pressure to reduce CO2 production inexorably rise.

Access to Distance Education

Perhaps the overwhelmingly important characteristic of distance education for many people is its accessibility. With the advent of distance learning, a student no longer had to travel to a fixed location several times a week. No longer did they have to be at a specific place at a specific time. They could study largely at their own time and wherever they happened to be, only needing a home address for the delivery of their correspondence texts. Indeed, even that was not essential—an early student I met was of “no fixed abode” and used a local laundromat as his delivery point for his course materials. And of course there are many students with disabilities for whom distance education is the only possible way of learning—see Chapter 14.

This accessibility is not only in physical terms, but in social and psychological terms as well. Distance students can try study completely privately, secure that no one but their family need know about their studies and any potential failure unless they choose to share that knowledge. Some students experience social anxiety—up to a third of students in face-to-face education can experience acute social anxiety in public learning situations such as taking part in discussions or giving presentations (Russell, 2008). For such students the isolation of distance learning can paradoxically be a blessing—at least, when they first start learning.

The development of e-learning now even obviates the need for materials to be delivered by snail mail—conventional portal delivery services—as course materials and support can be delivered over the internet to a student's computer, with assignments returned the same way.

The more recent growth of Open Educational Resources (OERs), where institutions make their course materials (texts, video clips, podcasts and so on—now often referred to as “learning objects”) freely available on the web, may also contribute to access. One of the first initiatives was started by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2001, with its MIT OpenCourseWare project: http://ocw.mit.edu/index.htm, followed by several others, for example, the U.K. Open University's OpenLearn Project: http://www.open.edu/openlearn in conjunction with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Following on from OERs are “MOOCs” —Massive Open Online Courses—such as the recent Stanford course in Artificial Intelligence, which had 160,000 students, some 23,000 of whom were given a non-accredited certificate as a downloadable pdf at the end of the course (a “pass” rate of approximately 14%, which as we will see is roughly average for distance education courses).

However, it is not yet clear just how e-learning and OERs will contribute to making education more accessible. Indeed, there are serious issues about exclusion—in the United States at the time of writing (2012), some 23% of the population have no internet access at home (and of the remainder some still only have dial-up); in the U.K. the figure is 30%. While some of these households in both countries will have access through work internet cafes and so on, this may be insufficient for study. And such households will be very heavily concentrated in the already educationally disadvantaged parts of both populations. I will return to this issue in Chapter 8.

The levels of internet access in the developing world are considerably less than the above, so distance education institutions that focus on e-learning and OERs, while facilitating access to some, are also excluding many others from their resources. Since e-learning is no less expensive than conventional distance education (Rumble 2004) and yet, as we shall see, apparently so far no more effective in producing student success, it means that resources are then directed away from people who are often in most need of them. It is unlikely that the rush to e-learning will slow in the lifetime of this book, but this caveat about access and success will occur again in the text and the book will take a skeptical, evidence-based attitude to e-learning, while not agreeing with Professor David Noble (1998) that “e-learning is a technological tapeworm in the guts of higher education” (p. 5). The book's approach will be more in line with Professor Martin Trow's assertion (2000) on the subject of e-learning, that “the future of learning will see a combination of traditional and distance learning rather than a replacement of traditional forms. But the short history of the computer has provided us with many surprises, some of them even welcome.”

Quality of Distance Education

For many years one of the weaknesses of distance education was thought to be its quality—that it was inferior in every respect to conventional higher education. This may well have been true during the era of the correspondence colleges, but I think it would be hard these days to maintain that a distance degree is inherently inferior to a degree from a conventional university—as long as the distance degree was awarded from an accredited institution. (One of the problems of distance education is certainly the growth in “degree mills”—spurious online distance education institutions that can look very convincing.)

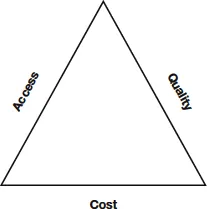

It may be true that until the advent of the internet distance education was in the grip of an “iron triangle” whose sides were respectively cost, access and quality (Daniel 2011)—see Figure 1.2. Daniel's iron triangle suggests that in pre-internet distance education, altering any one of the sides would change the other two. So, for example, trying to increase quality would either increase cost or lower access, or both. Correspondingly, increasing access would either lower quality or increase cost, or both. Daniel's thesis was that the technology revolution would break this iron triangle and allow for increasing quality and access while lowering cost.

However, this triangle really needs the metaphysical impossibility of a fourth side—a side representing “output”—the ability of distance education to produce graduates. Because, apart from issues of access, cost and quality, there is a very serious elephant in the distance education room—the elephant of student dropout.

Figure 1.2 Daniel's (2011) “iron triangle” of quality, access and cost

Student Dropout in Distance Education

While there has been a huge growth in distance learning in the last 30 or so years, this growth often disguises a fundamental weakness at its root. That fundamental weakness is its dropout rate.

Dropout rates are notoriously difficult to discover (institutions are hardly likely to publicize them to any extent) or to estimate (What constitutes a fully registered student? What are they studying for? How long are they likely to take?). But it ...