- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Through Projects

About this book

Designed for those developing open or distance learning materials, this guide describes various kinds of projects along with the appropriate tuition methods, assessment procedures and the expected learning outcome. The tutor's role as supervisor is examined, as are grading and assessment methods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 8

Materials

Presenting projects to open and distance learning students needs careful planning as they are likely to have less face-to-face support from their tutor than the conventional student. In effect the teacher needs to anticipate many of the problems the student may have, exemplify what is required, advise the student on the possibilities, build in structures to support them and make certain the project is ‘doable’.

Even staff who are philosophically disinclined to provide much structure (fearing this is a form of control that will inhibit students) have often found the need to introduce more structure over time. This trend seems to apply even in the extreme case of institutions committed to independent study and a project orientation. For example, the School for Independent Study at Lancaster found they had to be much more explicit about their criteria for assessment. The School for Independent Study at the University of East London introduced much more structure in the early planning stages, including training workshops (Percy and Ramsden, 1980). The University of Aalberg, which operates a project-based curriculum, has also now introduced more structured projects earlier in the curriculum (Olsen and Laursen, 1991).

Ironically, in terms of staff preparation time, the unstructured project is often less time-consuming than the structured one. Since unstructured projects are fairly open-ended they need less written support and are often supported only by a study guide outlining the procedure rather than providing content. Structured projects on the other hand often take a lot of preparation time, for example, collecting pertinent case study material, checking that a research design will work or that sources of data are available. Anecdotal evidence suggests that staff can take longer to prepare a structured project than conventional open learning material.

Not that unstructured projects are a soft option, as any saving in preparation time tends to be offset by the need to provide extra monitoring and facilitation of the students’ projects. Kennedy (1982) points out that the learner-directed approach inherent in project work is neither unsystematic nor unstructured: ‘It requires careful planning and monitoring by the tutor and a detailed framework of organisation’.

There are basically six ways to support open learning projects, through written material, audio-visual media, computers, assessment devices, tuition and scheduling. Scheduling was discussed in the last chapter; material, media and computing support are discussed in this chapter; and assessment and tuition in the ensuing chapters.

Students need to have a clear idea of what is entailed in the project at the outset. I found the Open University project courses rated as most difficult by students (which over a fifth found very difficult) were those where students were unclear what was expected. The difficulty derived from poor design, ie, a vague description or a confusing one, a demand for statistical competence among the non-numerate, or a creative response in areas that were utterly new to students (Henry, 1978b, p. 166).

Written material

In an open learning project the teacher needs to pre-specify a lot of the things a tutor might normally be able to discuss with the student in person. This entails:

• offering extra guidance

• forewarning students of pitfalls

• providing a fall-back project.

Offering extra guidance

Students undertaking project work are often given very little in the way of back-up support material. This is a pity as studies suggest that where such support is offered it is much appreciated, provided it is relevant to undertaking the project. As shown in Figure 8.1, the OU study found two-thirds of students wanted more written help to write up their project (presumably on the expected format). Just under half wanted written help with analysing material; this proportion rose slightly to just over half on the survey projects requiring numerical analysis, whereas only around two-fifths wanted the extra written assistance to help choose their project topic and collect data.

Figure 8.1 Percentage of students wanting more help with project from course material

Section B has already given some indication of the type of information and guidance required; this is summarized below:

| Type of guidance required | |

| To indicate scope: | list project topics and provide sample projects |

| To assist data collection: | list type of material and institutions, offer guide to local and national sources |

| To assist data analysis: | demonstrate techniques and methods |

| To assist project report: | provide format guidelines, assessment criteria and sample reports. |

Topic list

First the student needs help with deciding on a topic. In addition to a general description of what is required, some project courses offer an indicative list of possible topics. The fear that adult open learners will merely copy one of these topics seems ill-founded. Such students have had time to develop interests and very rarely opt for one of the suggested topics, but they find a list of sample topics valuable as an indicator of the type of topic expected (Henry, 1978b).

Some project courses go to greater lengths. The OU design course ‘Man-made Futures’ provided its students with a game designed to help them decide on a topic; it has to be said this met with mixed reaction.

Data source information

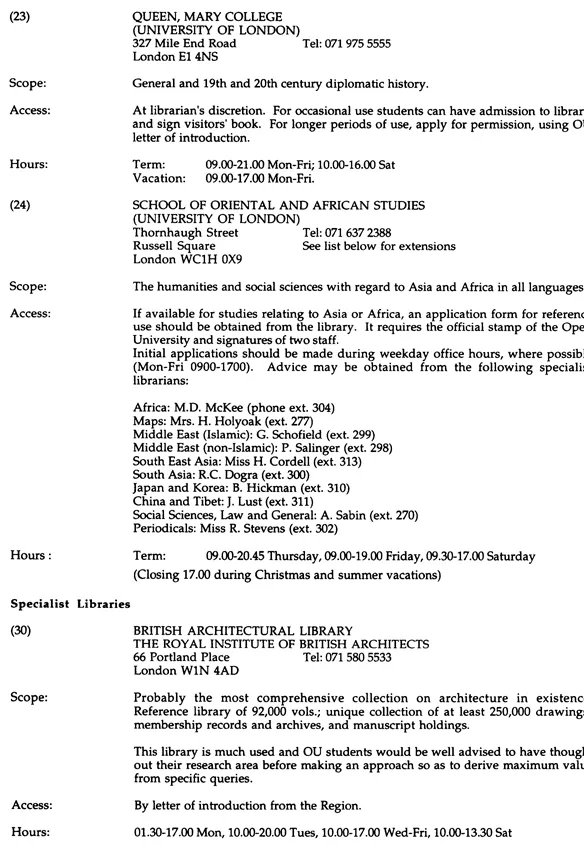

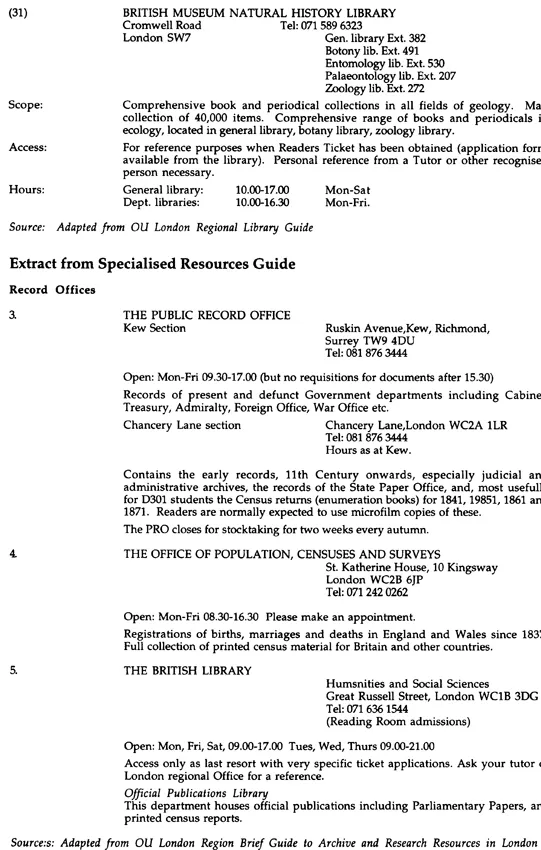

Distance learning students need some indication of where they can be expected to find appropriate material. For many humanities projects this will largely comprise local libraries, public record offices and any national societies pertinent to the particular area. Open learners appreciate names, addresses and telephone numbers so they can plan their visits in advance.

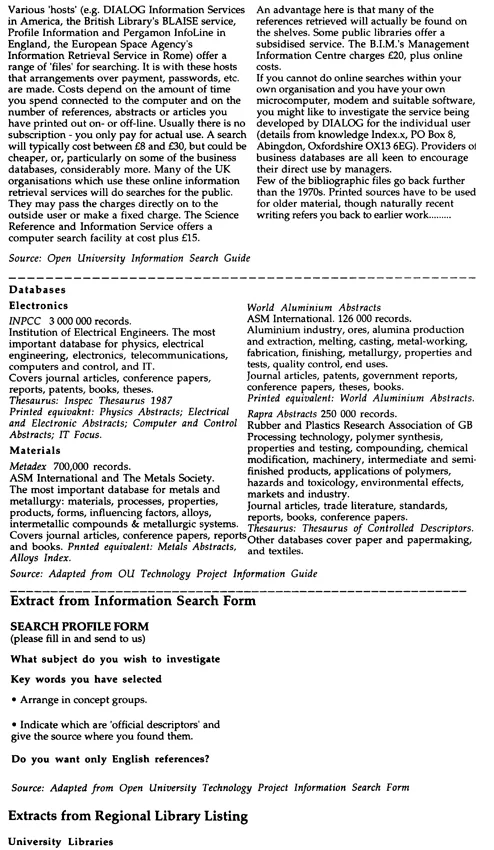

Students may also appreciate some indication of how to find their way around a library, the databases they can access, an introduction to the indexing system and an overview of key abstracts and reference texts and journals in the field. Librarians are often very willing to provide this kind of service. A booklet describing information sources can be given to students on many different courses or fairly easily customized for each, so in the long run it can save staff time. Illustrations of the type of information the OU has provided are given in Figure 8.2. Commercial abstracting and indexing services plus databases on CD-ROM are also available (eg, Bowker Sauer catalogue).

Figure 8.2 Extract from Information Search Guide

Source:s: Adapted from OU London Region Brief Guide to Archive and Research Resources in London

Over a period of years students and tutors may build up knowledge about organizations in the area which are willing to assist students with their project and those that are not. In conventional institutions this information passes along the grapevine like wildfire, but in open and distance learning there may be less opportunity for this transfer of information. A ‘Sources of information guide’ could usefully include students’ comments and advice on how best to approach certain institutions and which ones to avoid.

Data analysis and report

At the analysis stage students need some indication of what to do with their data. There is great scope for demonstrating appropriate methods of analysis through ODL materials. Research projects may need quite a lot of support at this stage. Staff may be able to recommend a book which covers the necessary ground. For example, Bell (1993) describes some of the typical research procedures used in projects in a book originally developed in the context of open learning, and many psychology departments use Greene and D’Oliveira’s (1982) excellent statistics book as a teaching text. In other situations staff may need to prepare material especially. For example, the OU research methods course included a detailed evaluation of two pieces of research on crime, designed to demonstrate the type of approach required for an evaluation project.

All students also need some guidelines on the expected report format and assessment criteria. They also appreciate the opportunity to peruse other students’ sample reports. Some course teams abbreviate two or three of these and send them to students. Others hold a stock of such reports for loan or make them available at a particular time, eg, at residential school.

Forewarning students of pitfalls

Students working in isolation benefit from quite explicit warnings about the common pitfalls in project work. Some of the key points that apply to most projects are:

• check the information is available

• do not be overambitious

• pick a site near home/work

• start collecting information early

• avoid being side-tracked

• avoid neglecting other course work

• forewarn of possible expense

• encourage students to contact their tutor

• encourage students to submit non-assessed outlines and draft reports.

The reasons for these warnings are elaborated elsewhere in this book. For example, as explained in Chapter 4, students need to be encouraged to check that information will be available and pick a feasible project topic. They need to be encouraged to narrow down their choice to one smallish area that can be covered in the time available. The importance of picking a local site, starting collecting information early and the dangers of side-tracking and neglecting other course work are elaborated in Chapter 5. The importance of contacting the tutor and ways of encouraging this are elaborated in .

Expense

Projects can involve students in expenses they do not normally incur, for example, the travel costs associated with field visits and interviews, the telephone costs of arranging access and finding out what is available, the cost of copies of documents, postage, equipment, materials, books, journals, presentation folders and photographs. It seems only fair to warn the student of possible expense. About a third to a half of the students on three-quarters of the projects in the OU study felt they should have been warned.

Personal projects

If I had known I had to tell my tutor all my thoughts I wouldn’t have taken it.

(ODL project student)

I object to self-analysis; these are very personal thoughts.

(ODL project student)

Many management and social science projects deal with very sensitive material and require students to undertake an analysis of themselves. Most students are more than happy to discuss their strengths and weaknesses in a project assignment but a significant minority find this very difficult, if not an unreasonable demand. With such projects it is important to make clear their personal nature at the outset. Tutors must also be very careful that they mark such projects sensitively, concentrating primarily on the way the project has been written up. Here it is a good idea to stress the importance of confidentiality. Students can be encouraged to use pseudonyms where necessary and tutors should respect the confidentiality of the material, avoiding showing the project report to other students, for example.

Providing a fall-back project

There are a number of situations where students might need fall-back projects, notably where students may end up with inadequate data through no fault of their own, and some course designers offer such fall-back projects. In research projects this will normally require students to analyse simulated data or a collection of case study materials. In humanities and other projects where these are not easily provided, the fall-back project may be of a different nature, for example a literature review. The OU geology course allows students having great difficulty finding information to use summer school data instead.

The housebound or prisoners are two more groups that may be unable to complete the original project and need a fall-back. Teachers have provided satisfactory projects for people in such positions by designing a project around items on television, newspapers or magazines. Staff so...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series editor's foreword

- Preface

- Characteristics

- Process

- Guidelines

- Appendix: The OU study

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching Through Projects by Jane Henry,Henry, Jane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.