- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Forms

About this book

This popular and influential work, translated here into English for the first time, argues that modern urbanism has upset the morphology of cities, abolished their streets and isolated their buildings. In tracing the stages of this transformation, this book presents the view that the urban tissue, the intermediate scale between the architecture of buildings and the diagrammatic layouts of town planning, is the essential framework for everyday life. Only by investigating the urban tissue will it be possible to understand the complex relationships between plot and built form, between streets and buildings and between these forms and design practices.

The chosen trail of the first French edition - Paris, London, Amsterdam, Frankfurt - is one of continuously evolving modernity. It outlines a history, which, in one century (1860-1960), completely changed the aspect of our towns and cities and transformed our way of life. The shock has been such that we are still looking for answers, still attempting to find urban forms that can accommodate present day ways of life and at the same time maintain the qualities of the traditional town.

This English edition brings the story forward to the present day and considers the impact of the New Urbanism in the United States, which, over the last decade, has sought to re-establish former relationships within the urban tissue.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture Design

CHAPTER 1

HAUSSMANNIEN PARIS: 1853–82

The transformation of Paris under Haussmann is of interest not only due to the fact that it gave the city the aspect that it still has today. Paris became a haussmannien city (with the help of the Third Republic), but it also became the ‘bourgeois city’ par excellence. With Haussmann, ‘the city becomes the institutional place of the modern bourgeois society’1 and, evidently, it is here where the essential interest of the Haussmannien interventions reside. They created a certain type of city, a space devised from the logic of the bourgeoisie, now the predominant class; they imposed a specific spatial model, which remains after Haussmann and the fall of the Empire and conditioned town planning at the beginning of the Third Republic.

THE BOURGEOIS CITY: THE GRAND PROJECTS OF PARIS

Haussmann took the oath as prefect of the Seine on 29 June 1853. His nomination to Paris2 had as its explicit aim the implementation of the large plans required by Napoléon III; the discussions following the oath taking dealt with this topic and on the means needed to achieve it. He immediately had to change the attitude of the Municipal Council, which was considered to be recalcitrant, even though it had been nominated by the government, and created an unofficial committee, which would have control of the large state plans and would function as a sort of private municipal council.3 This committee, which Haussmann considered unnecessary, did not meet more than once. Nevertheless, it is important, because it shows the type of relationship between the various authorities, government, municipality and administrations and it clearly defines the Bonapartiste political regime. The prefect had a privileged status and was classified as being in the private domain. It was executed with the minimum of publicity and through special channels in order to allow maximum efficiency.

From the time of his taking on this role, Haussmann took the opposite view to the administration of the previous prefect, Berger – whose hesitation with regard to action plans resembled those of Rambuteau, the prefect of Louis-Philippe. It was no more the case of administering the city ‘as a good father’, respecting the rules of prudence and with due care shown to private interventions. Haussmann's methods, like those of his predecessors, had the same relationship as the one between the new and aggressive capitalism of the merchant bank and the consummate capitalism of the first half of the century, the capitalism of the grand Parisian bank. They no more corresponded to ‘a period of moderate, but constant growth in production and income, 1815–1852’, a growth that still rested on an archaic structure, where wealth was built on agriculture and commerce, but not yet industry. On the contrary, at the heart of the ‘prosperity regime’ of the Empire, Haussmann's methods were there to stimulate growth. They were part of the new enterprising fervour, which promised ‘a perspective of rapid profits and an unlimited future for the banks’.4 This coincided with an unprecedented accumulation of capital (especially between 1852 and 1857 with some still good periods until 1866).

Haussmann developed, as a management method, the theory of productive expenditure. The point of departure was the traditional Parisian budget surplus, which is difficult to assess, but which, on 55 million francs in receipts, fell to 10 million, once the debts are deducted, if one can believe in Haussmann's analysis presented to a badly disposed, if not hostile, council. This was pushed up to 18 million francs in the budgetary projections for 1853 and which he found to be near to 24 million at the end of the exercise.5 The theory of productive expenditure recommends the use of the surplus, all or in parts, not for some direct short-term interventions, but to finance the interest on a considerable and long-term loan.6 But the municipal finances can face this discounting of a rapid and constant growth of resources only if it is based on a growth in economic activity, business and population.

The wealth of the taxpayers was the city's wealth. The best way to increase the budget was to make the taxpayers richer, and the very large projects were at the same time the instrument and the product of this strategy. The city was managed like a capitalist business. In fifteen years, the surplus borrowed against the ‘productive expenditure’ increased from 20 million to 200 million francs.7

But one cannot stress too highly the stimulative function of Paris's great projects vis-à-vis the development and improvement of the capitalist system after 1852. We know that the projects of the first network (1854–8) were carried out partly under public control by the city, which was its own developer, even though it had not yet sufficient technical and controlling expertise and was risking longer delays in their execution. This happened because the developers were not able to cope with the organization of very large building sites, being short of capital and without sufficient financial means. It was, in fact, necessary to deliver to the city some entirely completed and paved large arteries with laid-out and planted pavements. Haussmann's programme was, thus, a call for the intervention of large financial firms, which, following the Saint-Simonian principle of marrying banks with industries, gave rise to large projects and undertakings.

The Crédit foncier of the Péreire Brothers (founded in 1852), four-fifths of whose lending went to the property market, was Haussmann's chosen tool for financing the planning of Paris. The Crédit mobilier (Pereire, Morny and Fould, 1852), while being the bank of the industry, also financed some large estate companies such as: the Sociétéde l'Hotel et des Immeubles de la rue de Rivoli (1854), which became the Compagnie Immobilière de Paris in 1858. Shortly after 1863, it failed as the SociétéImmobilière de France, in a Marseille speculation, which expected too much from the opening of the Suez Canal (this did not happen until 1869).

The similarity of methods and aims between those large banking firms and Haussmann's productive spending was striking: he wanted to activate credit and drain vast markets by using large organizations capable of lending for the long term (this was a new technique in 1852). It was intended to direct the economy by founding large enterprises (this is again the Saint-Simonian idea). Haussmann could adopt these objectives as his own, since he had perfectly understood the methods and possibilities of investment banks and these were the methods that he applied in the management of Paris.

Obviously it was not presented in this way. Rather, Haussmann promoted a ‘cult of the Beautiful and the Good, with the beauty of nature as inspiration for great art’.8

The economic mechanism was concealed under the technical arguments, which in turn were hidden under aesthetic pretexts. Classical culture was used as reference, at least on the surface, and without being embarrassed by eclectic contaminations. In the city a rhetoric of axes, of squares marked by monuments, a network of monuments, whose returns were from now on visible, claimed to reproduce the forms codified in the classical system. We can observe that, whatever our judgements on aesthetic matters, the image of the capital city that Haussmann gave Paris entirely pleased the new bourgeoisie. The infatuation was complete. Zola says of the key characters of The Quarry that ‘the lovers felt the love of the new Paris’. Foreign tourists and visitors from the provinces, attracted by the exhibitions, returned to their homes amazed and conquered.

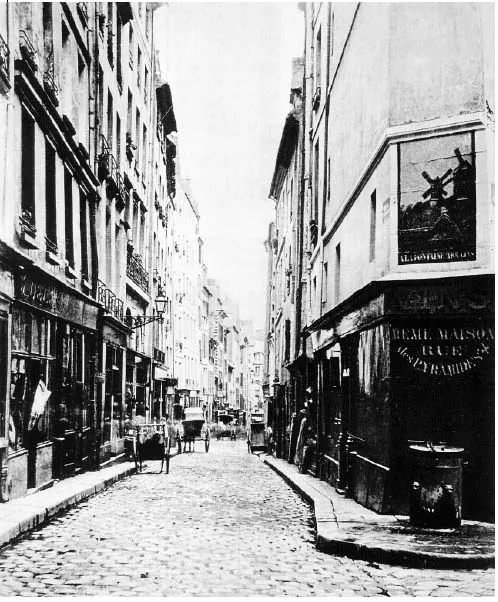

Figure 1

Paris and Haussmann.

a. The rue des Moineaux in 1860 (cliché Marville) before the opening of the avenue de l'Opéra.

a. The rue des Moineaux in 1860 (cliché Marville) before the opening of the avenue de l'Opéra.

If there was any criticism of the work of Haussmann, it was mainly political: it recognized in Haussmann ‘the typical Bonapartist civil servant’;9 it attacked, directly or indirectly, the unconditional bond that tied him to Napoléon III and to the political/financial system of the Empire. The ‘bourgeois’ republicans would only need the change of government in 1870 to turn over their criticism and leave to the Third Republic the task of completing what had been started. The criticism of the Orleanistes coincided with that of the old banking system, which was annoyed by the unorthodox audacity of the new commercial banks. Their spokesman, Thiers, came to pour out his criticism from his home in the place Saint-Georges, in the centre of the Dosne housing development of 1824 (Thiers was Dosne's son-in-law) – that is to say in the centre of one of those speculative operations of the Restoration, whose methods had been overtaken by Haussmann. With regard to the criticism of the Radicals, it was the Commune that managed the project and it was no more mentioned than it was implemented.

b. The avenue de l'Opéra today.

By making the administrative circumscription coincide with the defensive walls built in 1843, Haussmann defined the framework into which the evolution of Paris would take place up to today. Simultaneously, the interventions that took place in the historical centre led to the disappearance of popular areas, with the intention of giving a ‘modern’ image, appropriate to a commercial and cosmopolitan city.

The technical challenge was that of modernization and sanitation and, more importantly, the improvement of living conditions, transport and infrastructure. Haussmann's city experienced the most profound structural change to become a planned city. The notion of route was transformed, thus allowing the diversification and multiplication of distributive functions in a complex context with an efficient distribution of people, food, water and gas, and the removal of waste. Facilities, in the contemporary meaning, suddenly appeared everywhere: town halls, offices, ministries, schools, post offices, markets, abattoirs, hospitals, prisons, barracks, chambers of commerce, stations and so forth. The challenge was to distribute these facilities in the urban structure and to allow them to develop and expand.10 To the functional specialization, which in itself implied the notion of facility, was related a goal of systematization and control, of which they became a tool in their relationship to the urban structure. The identification of a hierarchy was established by the road network and by the facilities that it distributed. The setting up of these complex mechanisms emphasized the differences that were supported an ideology of separation, the practice of zoning.

This strategy of control and separation, which is the ultimate result of Haussmannization, becomes clearer when one discovers that, between 1835 and 1848, ‘Paris had become the biggest industrial city in the world’11 with more than 400,000 workers employed in industry out of a total population of 1 million inhabitants in 1846. The embellishments of the Paris of Napoléon III are, first, a result of a problem of quantity: in absolute terms, since the city had already more than a million inhabitants in 1846; then in terms of growth, because, with the same boundaries, those of the Thiers enclosure, the population practically doubled, going from 1,200,000 inhabitants in 1846 to 1,970,000 in 1870, according to the last estimate of Haussmann.12 But, beyond quantity – from then onwards, Paris must be treated as a very big city – there was the problem of the relationship of the social actors who made up these numbers. In the light of such a large number of workers and after the many ups and downs of the Second Republic, complacently exaggerated as ‘great fears’ by the bourgeoisie, the relationship between the domineering and the dominated classes was sharply defined. And the bourgeoisie, which took the initiative and was at the zenith of its power, set out all its tools of control. A new type of space took shape, not totally dissociated from the old space, but capable of reinterpreting it, to reproduce or to deviate its forming mechanisms, to develop them into a more and more ample and coherent project. The aim of our study is, first, to describe Haussmann's spatial models, not from an exhaustive analysis of the urban whole, but starting from one urban element that is at the same time characteristic and essential: the block. The block dominates our perspective; but it is necessary to ask how it was produced and how it was organized in the structure of the haussmannien city.

MODES OF INTERVENTION IN THE CITY

THE NETWORK OF PERCÉES

The existence of a plan, drawn by the very hand of Napoléon III, as many witnesses attest,13 would lead us to expect a global and coherent scheme for Paris. Several critics14 have insisted on Haussmann's ability to control the whole city, something that is quite in contrast with previous practice, which fell short of wide-ranging actions and was quite incapable of conceiving a plan at the level of the urban whole.15 The setting up of a developed administrative and technical tool, the Direction des Travaux de la Seine, could be interpreted as the clearest proof of the global dimension of Haussmann's concerns.

However, one must not think that the control over the city by Haussmann happened everywhere, nor that it was felt at all levels and affected all authorities. Haussmann was far from having to create a...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the First English-language Edition

- Introduction to the Second French Edition

- CHAPTER 1: HAUSSMANNIEN PARIS: 1853–82

- CHAPTER 2: LONDON: THE GARDEN CITIES, 1905–25

- CHAPTER 3: THE EXTENSION OF AMSTERDAM: 1913–34

- CHAPTER 4: THE NEW FRANKFURT AND ERNST MAY: 1925–30

- CHAPTER 5: LE CORBUSIER AND THE CITÉ RADIEUSE

- CHAPTER 6: THE METAMORPHOSIS OF THE BLOCK AND THE PRACTICE OF SPACE

- CHAPTER 7: THE DEVELOPMENT AND DIFFUSION OF ARCHITECTURAL MODELS

- CHAPTER 8: BUILDING THE CITY: 1975–95

- CHAPTER 9: AN ANGLO-AMERICAN POSTSCRIPT

- References

- Biographical Notes and Bibliography – Chapters One–Eight

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Urban Forms by Ivor Samuels,Phillippe Panerai,Jean Castex,Jean Charles Depaule in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.