1

Quality and quality assurance

1.1 WHAT IS QUALITY?

Quality may mean different things to different people. Some take it to represent customer satisfaction, others interpret it as compliance with contractual requirements, yet others equate it to attainment of prescribed standards. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) formally defines quality as the ‘totality of characteristics of an entity that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs’ (ISO, 1994a). Dr J.M.Juran, an international authority in quality management, perceives quality simply as ‘fitness for purpose’. Indeed, a product befitting its intended purpose would satisfy the user’s needs and expectations. The crucial point lies in making the purpose clear to all parties involved in the design and production.

In the context of quality management, quality is not an expression of excellence in a comparative sense. It is just an abbreviation for ‘desired quality’ that should be laid down as explicitly as possible. The supplier (producer), on the one hand, endeavours to attain the desired quality at optimum cost while the customer, on the other hand, requires confidence in the producer’s ability to deliver and consistently maintain that quality.

Quality of construction is even more difficult to define. First of all, the product is usually not a repetitive unit but a unique piece of work with specific characteristics. Taking building construction as an example, the product can be an entire building, a section of a building or just a prefabricated component that ultimately forms part of a building. Secondly, the needs to be satisfied include not only those of the client but also the expectations of the community into which the completed building will integrate. The construction cost and time of delivery are also important characteristics of quality. All these should be properly addressed in designing the building, and the outcome should be expressed unequivocally in drawings and specifications.

The quality of building work is difficult, and often impossible, to quantify since a lot of construction practices cannot be assessed in numerical terms. The framework of reference is commonly the appearance of the final product. ‘How good is good enough?’ is often a matter of personal judgement and consequently a subject of contention. In fact, a building is of good quality if it will function as intended for its design life. As the true quality of the building will not be revealed until many years after completion, the notion of quality can only be interpreted in terms of the design attributes. So far as the builder is concerned, it is fair to judge the quality of his work by the degree of compliance with stipulations in the contract, not only the technical specifications but also the contract sum and the contract period. His client cannot but be satisfied if the construction is executed as specified, within budget and on time. Therefore, a quality product of building construction is one that meets all contractual requirements (including statutory regulations) at optimum cost and time.

1.2 QUALITY CONTROL

Quality control refers to the activities that are carried out on the production line to prevent or eliminate causes of unsatisfactory performance. In the manufacturing industry, including production of ready-mixed concrete and fabrication of precast units, the major functions of quality control are control of incoming materials, monitoring of production processes and testing of the finished product.

Before production is commenced, an assessment is made of the minimum quality needed to satisfy the stated requirements and how that quality can be consistently achieved. An example is establishing the target mean strength of concrete on the basis of the specified characteristic strength and the estimated variability. During production, the strength of the concrete is continuously monitored via routine testing and statistical analysis of the test results, so as to detect at the earliest possible moment when either the mean strength or the variability of strength shows a significant change. The control mechanism then goes on to rectify the detected change, thereby preventing a potential problem from developing into a real one.

Very rigid rules for production control may be combined with lenient criteria of acceptance and trivial consequences of noncompliance. Alternatively the producer may be given greater freedom in production, but stringent acceptance criteria are set and severe penalties for noncompliance are imposed. Within the spectrum of possible combinations of production control and acceptance control, there will be an optimum that is the most economical to operate.

In the building industry, it is traditional practice to have separate contracts for design and construction, with the designer also taking up the role of supervision of construction. The quality of the finished works is controlled by way of inspection and testing as construction proceeds. For example, the quality of concrete and other materials on site is judged by random sampling and testing, and a thorough inspection of the finished works is performed without exception before final acceptance. The major drawback of this ‘inspectorial system’ of quality control is that it identifies the mistakes after the event. Even high strength concrete can be defective if it is not properly compacted and cured, and the potential hazard of steel corrosion will not surface until some years later. Many building defects are covered up during subsequent construction and consequently the quality of the finished works cannot be assessed by final inspection. Unlike consumer goods, defective building work is very difficult, if not impossible, to replace. The client is often left with the patched-up original which will be a source of recurrent trouble and huge expenditure in the years to come.

Regular supervision by the contractor’s staff themselves is undoubtedly the key to quality. There are, however, commercial and organizational pressures that often favour speed at the expense of quality. Sometimes poor workmanship is condoned to keep up with expected productivity or just labour. To show commitment to quality, senior management of the company must therefore provide adequate resources on site to avoid anybody cutting corners. Furthermore, a comprehensive record of inprocess inspection is essential to ensure that the intended verification is actually done. The extra efforts are managerial in nature and complementary to the operational techniques of quality control in assuring the quality of the product.

1.3 QUALITY ASSURANCE

Despite the wealth of site experience accumulated throughout the decades, one in ten building contracts still leads to client dissatisfaction and complaint against the contractor. A survey conducted by the Building Research Establishment in the United Kingdom indicates that 40% of building defects occur during the construction phase (BRE, 1982). In most cases, the defects are found to be the result of:

- misinterpretation of drawings and specifications;

- use of superseded drawings and specifications;

- poor communication with the architect/engineer, subcontractors and material suppliers;

- poor coordination of subcontracted work;

- ambiguous instructions or unqualified operators;

- inadequate supervision and verification on site.

It is obvious that defects arising in construction are mostly caused by poor management and communication. It is preclusive to assume that mistakes appearing on site are actually made on site. These mistakes may be traced back to the purchase of incorrect or incompatible materials and the failure to retrieve the out-dated drawings (Kettlewell, 1990). In other words, site problems can be the consequence of negligence or malpractice in the head office.

Consistent quality can only be achieved when such avoidable mistakes are avoided in the first instance. Preventive measures must be taken to minimize the risk of managerial and communication problems. This is the basic concept of quality assurance.

The performance of an individual in an organization could directly or indirectly affect the quality of the finished product. Responsibility for quality therefore stretches from the chief executive right down to the person-on-the-job. If consistent quality is to be assured, all staff in the organization, both in the head office and on site, must:

See Table

To practise quality assurance, an organization has to establish and maintain a quality management system (usually abbreviated to quality system) in its day-to-day operation. A quality system contains, among other things, a set of documented procedures for the various processes carried out by the organization. Implementing a quality system does not replace the existing quality control functions, nor does it result in more inspection and testing; it just ensures that the appropriate type and amount of verification is performed when and where it is planned to be done. In fact, a quality system embraces quality control as its technical arm. This is why a quality system is sometimes referred to as a QA/QC programme.

In short, quality assurance is oriented towards prevention of quality deficiencies. It aims at minimizing the risk of making mistakes in the first place, thereby avoiding the necessity for rework, repair or reject.

1.4 IS QUALITY ASSURANCE FOR CONSTRUCTION?

In the construction industry, quality assurance was first adopted in nuclear installation and offshore works mainly for safety and reliability reasons. Spread of the concepts to conventional types of construction has been gradual but slow. This is because the product of construction is in a sense always unique, unlike consumer goods which are repetitive in nature. The processes of construction involve a variety of professionals and tradesmen with a wide range of skills and level of education. The environment where these processes are carried out is often exposed to aggressive elements. Under such conditions, it is arguable whether the procedures can be standardized at all. Some contractors even think that trying to do so merely implants another layer of bureaucracy in the organization.

Despite the diversity of work handled by a construction company, the corporate procedures apply to all projects in varying degrees. Typical examples are tendering, procurement, document control and record keeping. A quality system may be set up to standardize these corporate procedures, with provision for preparation of a quality plan to cover the characteristics and specific requirements of a particular project.

It is unfortunate that adoption of quality assurance in the construction industry has been mainly client-led. Realizing that enforcement of the contract in law cannot undo any damage already done*, a progressive client, when awarding a contract, tends to take into account the contractor’s capability to ‘do it right first time, every time’—the underlying philosophy of quality assurance. There is a general movement towards making the implementation of a quality system a contractual requirement. Many government bodies responsible for public works and housing have begun to insist on an effective (or even certified) quality system as prerequisite for tendering. Public utilities companies are doing the same thing. Private developers with major projects in planning will follow suit. The basis of competition for business will shift from ‘price only’ to a combination of price and quality. If a contractor does not want to be excluded from bidding for available work, he should wait no more in establishing a quality system in his organization. Even if such external pressure is not on at the moment, he will be fighting a losing battle against his competitors who have enhanced their productivity through better quality management.

Just to satisfy a condition for tendering or contract may not be the best argument for practising quality assurance, but it is probably the most compelling reason in the first instance. However, the companies that benefit most from quality assurance are those which do so for the purpose of improving their own efficiency (Ashford, 1989). Notable changes are more effective communication, both within the organization and with outside bodies, less disruption of work and reduced spending on rework. These improvements lead to higher productivity on the one hand and client satisfaction on the other.

Of course it costs to implement and maintain a quality system. Significant investment in terms of money and staff time is needed en route to quality assurance, especially for document preparation and staff training. Some people see this as another item of overhead for the company. However, they should not lose sight of the savings that will accrue later with much reduced incidents of rework or reject. The overall quality related costs decrease rapidly as quality awareness among the staff increases.

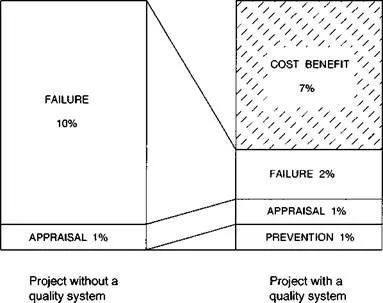

The actual cost is difficult to gauge and varies substantially with the size of the company and the scope of its operations. A questionnaire survey of contractors in Hong Kong has indicated that the setting up cost ranges from HK$1 million (US$128000) to HK$3 million (US$385000) with an average running cost of around 0.2% of contract value (Tam, 1996). An analysis of seven building projects of various sizes in Australia has demonstrated that ‘quality does not cost—it pays’ (Roberts, 1991). The results of the analysis are summarized in Fig. 1.1 in which the quality related costs are expressed as percentages of the total construction cost. Through the implementation of a proactive quality system that costs about 1% of the project value (the prevention cost), the expenditure as a result of repair etc. (the failure cost) drops from 10% to 2%, representing a saving of 7%. The economic benefit of preventive measures is obvious.

Quality assurance has also less obvious benefits. For a contracting company, a well-established quality system is a marketing tool, especially when the company has gone through third party certification. The quality system helps promote the image of the company and provide the much needed competitive edge in a competitive market. Improved market share will more than pay back the investment.

Fig. 1.1 Implementation of quality management (Roberts, 1991).

(reproduced by permission of Master Builders Australia)

The quality records generated by the quality system facilitate and strengthen the process of claims and, in case of counter-claims, provide a potential line of defence. Legal costs are minimized, should litigation be required at all.

1.5 SUMMARY

- Quality in general terms is ‘fitness for purpose’, but in building construction it is more appropriately i...