![]()

Part I

Introductions

![]()

Reading performance

A physiognomy

Meiling Cheng and Gabrielle H. Cody

And every “form” is a face looking at us.

Serge Daney, “The Tracking Shot in Kapo” (1992)

Serge Daney, a self-proclaimed “cinephile,” had a specific referent in mind when he made the general analogy between a form and a face. He later named this referent, “And then I see clearly why I have adopted cinema: so it could adopt me in return” (1992, online). Daney’s statement, however, carries greater resonance than the particular genre of his address, for his analogy redirects our modernist interest in knowing a given artwork’s intrinsic qualities to performative dynamics: the reciprocal impacts borne by the artwork and its beholder through their encounter. This transition from the ontological (the nature of an artwork) to the interactive (an artwork’s relationship with its beholder) implied by Daney’s remark opens up the cultural space for our book, Reading Contemporary Performance: Theatricality Across Genres, to claim that performance has emerged as one of the most mobile, adaptable, and sharable ways for us to experience the world, look into ourselves, and communicate with others. We have entered an era in which we care less about what a performance is than about what it does for us and how we can return the favor.

But does performance have a form that can serve as its face? Daney’s daring metaphorical schema (every form = its face) asserts that it does: even formlessness is a form. By giving a face to an art form, Daney evokes certain attributes—such as agency, affect, and expression—that we usually associate with a face in the act of looking and effectively makes the artwork, in whatever form it takes, an entity equivalent in status to the human agent who engages with it. Daney’s conceptual paradigm relocates an artwork’s purpose from exercising its unique being to its dialogic function, as it develops a relationship with us, the people who choose to experience it. Simultaneously, the same paradigm exposes our role in this relationship as not always the subjects actively doing the “looking,” but also the objects being “looked at” by the artwork. At the heart of Daney’s premise lies the mystery of the encounter between two parties, who share equal status as reciprocal partners and interacting performers, even though they may reside within different levels of reality.

Since Daney’s paradigm defines this meeting from the perspective of the artwork itself as a looking subject, we might approach the same process from our position as the one in thrall to the look. Thus, let’s consider our options: If indeed every form—including this book, Reading Contemporary Performance (alias, RCP)—is a face looking at us, then why and how do we look back?

The answers to the “Why …?” question are likely to be existential and relatively unique to each individual. Why do we want to know about performance? Why do we read this book? Why do we dance to a sad song and weep from happiness? Why do we brave through our constant aging and incremental dying to still try to “perform our best” every day, documenting our transitory faces with countless selfies and sending them tumbling through electronic ether? Why not—if that’s the way we greet the world and amuse our friends, while investing in our digital immortality. What does Serge Daney say?

Our average guru’s answer to the “Why …?” question pivots on the consensual pleasure of mutual adoption: “I’ve adopted cinema, so cinema could adopt me!” Provocatively, Daney’s answer echoes a simple calculation in physics: I cannot see my own face without being seen by another face—the face of a mirror, the face of water, or the face of my reflection inside another person’s pupils. Even when I don’t see my face literally reflected on the face of, say, a rock, I might trace the rock’s sedimented patterns and recognize how time has produced similar wrinkles on my face to make me as stoic, solid, still, and enduring as a rock. Consciously or not, we look into and look back at the face looking at us in search of our own possible faces. In other words, we would read this particular face, RCP, to see how the reading may change us and how we may in turn change RCP. What happens between RCP and us during the protracted reading process is a contingent concatenation of performances, which promise, if nothing else, to change our perceptions about the world around us.

Compared with the idiosyncratic “Why …?” question, the “How …?” question is collaborative. Answers to the “How …?” will multiply, evolve, migrate, mutate, proliferate, and accumulate upon one another through their respondents’ aggregated labors and for the sake of their common benefits. It surely takes more than one book and a few centuries to respond to the “How …?” question. So we might as well begin again, here and now, by raising the question that we earlier put off: “What is the face of the form that RCP desires to look back at, to reflect, to touch, and to talk to, to draw on, to play with, to tear apart, to ponder, to imitate, and to read?” Suppose that the face has no eyes, no nose, no ears, nor jaw, how do we start?

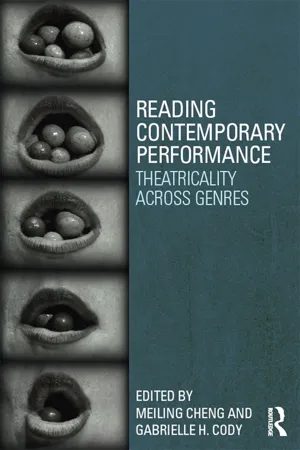

From a video still image, you see the close-up shot of a mouth, with lips ajar and a number of stone marbles weighing on its tongue. You click your computer cursor on the triangular sign activating “Play” and the mouth begins moving, bringing the stones inside its orifice into rolling motions. These stones orbit around one another like an acrobatic ensemble and constantly shift their positions on the mobile bridge of a tongue, making dull grating sounds as their moist surfaces touch. Revolving rhythmically in their discrete but intimate proximity, these spherical players can barely remain on their stage-two just slip past the guardian teeth and almost fall from the lips’ edge, while others sway precariously against the backdrop of a larynx.

Spotlighted with a framing border and a sans-serif font, our narrative offers a brief case study of a viewer’s encounter with one of many faces of contemporary performance. In this context, the “viewer” is anyone who has the means of interfacing with a digitized video sequence accessible on the Internet and who has an interest in initiating a fleeting sensory contact with what the online portal might proffer. To launch this “sensory contact” entails a viewer’s own performance through several actions: (1) make a choice to access a virtual object (a face/form) that promises something more than its initial still image; (2) engage with the haptic experience of holding the computer devices required for the access; (3) watch a recording of an action executed by a troupe of performers, including an acrobatic mouth, two rows of teeth, a skillful tongue, a bunch of stones set to occupy the mouth, and a tantalizing larynx. After most likely a private screening from a computer monitor, the viewer, if seduced by these apparently constricted yet all-the-more-so virtuosic performers, might choose to generate more follow-up actions. RCP suggests that the act of reading a performance usually happens not with the first but rather with the follow-up set of a viewer’s performance. Reading a performance is a repeat performance.

In a world suffused with traces of performance—such as pop-up ads, Facebook postings, Twitter tweets, movie previews, YouTube videos, even a sad lost dog poster with a guaranteed reward and a detachable list of phone numbers—a person’s choice to experience more than haphazard fragments of a particular performance will often produce an instant series of shifting roles. By giving permission to linger with the face of another form, the person changes from a random passer-by to a volitional actor, from an embodied sentient being who performs the tasks of daily living to one who interrupts the flow of quotidian routines so as to pay attention to another being, from a perceiver of information and a consumer of data streams to a reader, one potentially able to process, interpret, question, critique, and make something out of that same information, henceforth altering the information.

If our exemplary viewer serves as a prototypical reader addressed by RCP, then how can we characterize the video piece we described earlier as a face of contemporary performance? At our spectacle-saturated contemporary moment, we often encounter the face of a performance first as an anonymous image: a mouth strangely stuffed with stones, for example. Something about this image—perhaps the slight dread of suffocation it evokes, or the cunning configuration of those stones—compels our attention, urging us to find out more, if only to make sense of this peculiar sight. As RCP proposes, the instant we transition from indifference, to interest, to initiating a relationship with what that image might bring establishes the condition for us to begin conceptualizing what we experience subsequently as a performance. Specifically, we understand a performance as an intentional construct emerging out of the creative ecology of five irreducible, interwoven, and mutually affecting elements: the “time-space-action-performer-audience matrix” of theatricality (Cheng 2002: 278). Any element in this dynamic theatrical matrix may function as an entry point to stimulate the concomitant formation and motion of the other four elements, thereby constituting an experiential event that we appreciate as a performance.

In our opening case study, for instance, the entry point is the viewer, or an audience of one. This audience’s choice to instigate an exchange with an intriguing image triggers at least two simultaneous performances. As we explored earlier, one of these performances is self-generating, when the audience doubles as the performer to execute a durational action of observing a video recording. The time for this performance coincides with the audience-performer’s chosen duration, which might last from a few seconds to the roughly one-minute length of the video sequence, or longer, with repeated viewings. The space is the virtual interface as well as the actual place where the mechanism enabling this interface resides. The site of this performance emerges as the conjunction of space and time designated by the performed action: while the virtual site engaged by the audience-performer’s observation is both somewhere out there (on the Web) and in here (inside the viewer’s mind), the actual site might be as small, near, and dear as a smart phone screen, along with the tinier cognitive nerves fired up by synapses within the observer’s brain.

Meanwhile, concurrent with this audience-performer’s enactment is a parallel performance by our case study’s other subject, faces of which adorn the cover of RCP. The mouth starts moving, the stones on its tongue spinning, making grating sounds. After approximately one minute, the performance stops, while the mouth remains agape, restored to its former anonymity, which suddenly feels unbearable to us. We succumb to this scene of seduction by searching further; now we want to be able to read the performance.

Reading as a query for facts: what we watched and described in our case study is an excerpt from (aleph • video) (1992/93), made by artist Ann Hamilton (annhamiltonstudio.com 2014). Hamilton first shot on a beta tape her own mouth, teeth, and tongue manipulating a number of stone marbles to produce a thirty-minute video piece, shown in a continuous loop from a small television monitor (with a 3.5 × 4.5 inches screen) inset onto a wall, to form part of her site-specific installation aleph (1992) at the List Visual Arts Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Reading as historiographic investigation: Although Hamilton’s 1992 installation is no longer extant, (aleph • video) has been converted into a digital format and, in its limited version, is available for online public access in a virtual gallery via the artist’s website. The video excerpt serves as both a mnemonic reference to the ephemeral scenographic environment in which it once participated and an archival sampling of a collectible video piece, editioned by the artist and acquired by a museum (Guggenheim, see Ragheb 2015). The migratory path that the video has taken (studio -> installation -> internet -> any conceivable elsewhere) typifies how performative artworks might travel and circulate in our globalized technological economy. A transient performance piece may now lead an afterlife as variously reconfigured commodities branded with an artist’s signature.

Reading as comparing clues: According to Hamilton, her piece’s title was inspired by Ivan Illich and Barry Sanders’s explication that “the sound and the name of the [Semitic] letter ‘aleph’ derive from the shape the larynx takes as it moves from silence to speech” (Simon 2006; see also Illich and Sanders 1989). Our previous reading approaches the action of (aleph • video) as a performance of competence, in which an ensemble of stones behave like autonomous performers to accomplish clever relational routines in a theatre made of human organs. The stones play for our diversion. The new clue from the artist’s statement, however, recasts the piece’s action in a linguistic framework, calling attention, instead, to its drama of necessity, a suspenseful labor through which a speaker strives to move “from silence to speech.” In this light, the stones, with the lips and tongue, teeth and gums, and even the larynx, all become supporting players for the featured performance of the speaking subject.

Reading as decipherment: Our newly clued reading of (aleph • video) as a performer’s gestural production of sounds guides us to see her mouth less as a site where performance happens than as an instrument with which the speaker plays, vacillating between silences and speeches. We already knew that the mouth in (aleph • video) belongs to Hamilton—who wears a dark lipstick—but why didn’t she show her entire face? This exclusive focus on a mouth-in-action, as we may reasonably decipher, serves to obscure the performer’s individual identity and heighten the mouth’s status as a common facial organ through which we, the human species, produce speech and develop language. Thus, Hamilton chose a small and relatively anonymous (being eyeless/soulless, etc.) part of her face to substitute for the highly evolved mouth of Homo sapiens, capable of producing silence and speech, plus many other oral variations in between. If so, then what do those stones stand for?

Reading as all you can take: There are no stones in (aleph • video), for all is digital! As homage to one of the best contemporary film epics of our time, The Matrix (1999), we sample and remix a line from it—“There is no spoon”—to characterize the mutability of those stones rolling in the mouth on the cover/face of RCP. Once upon a time, those stones were real! They were the building blocks, if not the alphabet, for Hamilton’s self-invented hybrid speech in her initial recorded live performance. This hybrid speech comprises disparate elements rarely used in the so-called conventional human tongues: the speaker’s conjoint senses of touch and taste; the athleticism of nerves-laden labial muscles around the lips; and the insertion of material sonic components (the actual stones) into the speech system. Yet, insofar as Hamilton’s hybrid speech is not widely recognized, practiced, and exchanged as such, the stones interspersed in her system of orature exist merely as linguistic embryos, or premature signifiers, those sign-objects that may potentially become codified as the signified, as the meaning-carrying entities capable of facilitating linguistic communication. At present, these stones are more like slippery notes in a song than legible letters in a speech.

RCP delights in collecting and cultivating these not-quite-stones. Precisely because of their embryonic state, the stones inhabit the realm of the edgy imaginable, a delirious liminal zone where symbols sit next to tools neighboring similes side by side icons flanking metaphors across hypotheses and adjacent to functions. Infinitely malleable, these stones are ready to be adopted by those who are ready to adopt and be adopted by contemporary performance.

![]()

Theatr icality across genres

Gabrielle H. Cody and Meiling Cheng

“Theatricality” was the title of the 20th episode of the television series Glee, which premiered in 2010, and featured its female club members paying homage to Lady Gaga. The Glee cast performed in a selection of Mother Monster’s costumes,...