eBook - ePub

MoCap for Artists

Workflow and Techniques for Motion Capture

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Make motion capture part of your graphics and effects arsenal. This introduction to motion capture principles and techniques delivers a working understanding of today's state-of-the-art systems and workflows without the arcane pseudocodes and equations. Learn about the alternative systems, how they have evolved, and how they are typically used, as well as tried-and-true workflows that you can put to work for optimal effect. Demo files and tutorials provided on the downloadable resources deliver first-hand experience with some of the core processes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.1 About This Book

Motion capture (mocap) is sampling and recording motion of humans, animals, and inanimate objects as 3D data. The data can be used to study motion or to give an illusion of life to 3D computer models. Since most mocap applications today require special equipment there are still a limited number of companies, schools, and organizations that are utilizing mocap technology. Outside the film industry, army, and medicine, there are not too many people who know what mocap is. However, most people, even small children, have seen the films, games, and TV commercials for which mocap technology is used. In that sense mocap is in our everyday life.

The main goal of this book is to help you understand steps and techniques that are essential in a workflow or pipeline for producing a 3D character animation using mocap technology. Capturing data using mocap equipment is, of course, the essential part of the pipeline, but equally important are the things we do before and after capturing data, that is preproduction (planning), data cleaning and editing, and data applications. Without a well-thought-out preproduction for a project, the project is destined to fail or go through preventable difficulties. It cannot be emphasized enough that good preproduction is a key to the success of a project. After capture sessions, data needs to be cleaned, edited, and applied to a 3D model. Applications are getting better every year but they are tools, that is, technology does not create arts, you do. You are the creator and decision-maker.

Another key to success is setting up a reliable pipeline that suits your needs and environment. We’ve heard about production companies deciding to use mocap for particular projects, believing that mocap would cut their production cost and time, and giving up on mocap quickly after finding that mocap was neither quick nor cheap. Mocap disaster stories are often caused by the lack of a reliable production pipeline. Mocap technology can be effectively used once a production pipeline is established. For the first project or two, you will be hammering kinks out of your production pipeline while the project is moving through the pipeline. Thus, greater productivity shouldn’t be expected immediately after introducing mocap technology into the production environment.

This book is written for artists, educators, and students who want to create 3D animation for films and games using mocap technology. Familiarity with basic concepts of 3D animation, such as the principles of animation and inverse kinematics is expected. In the rest of this chapter we look at the history of mocap and types of mocap systems. We detail the preproduction in Chapter 2 and pipeline in Chapter 3, and introduce you to cleaning and editing data in Chapter 4. Skeletal data editing is explained in Chapter 5. Chapters 6–8 are about applying data to 3D models. In Chapter 6 we show you simple cases of data applications. In Chapter 7’ we discuss mapping multiple motions and taking motions apart. In Chapter 8’ we explain how you can integrate data into rigs. Special issues about hand capture are discussed in Chapter 9, facial capture in Chapter 10, and puppetry capture in Chapter 11. Chapter 12 covers mocap data types and formats, and mathematical concepts that are useful to know when you are setting up or troubleshooting a production pipeline.

We suggest that you read through this book once before you start a mocap project, and read it again as you go through your project pipeline.

1.2 History of Mocap

The development of modern day mocap technology has been led by the medical science, army, and computer generated imagery (CGI) field where it is used for a wide variety of purposes. It seems that mocap technology could not exist without the computer. However, there were early successful attempts to capture motion long before the computer technology became available. The purpose of this section is to shed light on some of the pioneers in mocap in the 19th and 20th centuries: this is not our attempt to list all the achievements on which today’s mocap technology is built upon.

1.2.1 Early attempts

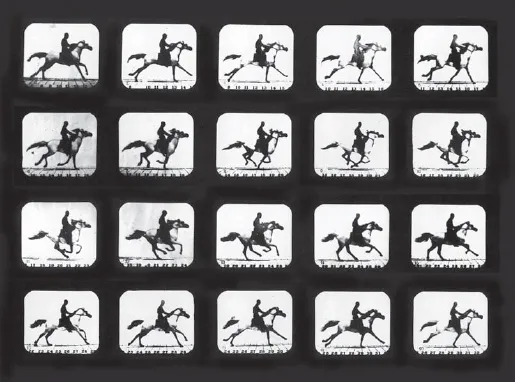

Eadweard Muybridge (1830 –1904) was born in England and became a popular landscape photographer in San Francisco. It is said that in 1872 Leland Stanford (California governor, president of the Central Pacific Railroad, and founder of Stanford University) hired Muybridge to settle a $25,000 bet on whether all four feet of a horse leave the ground simultaneously or not. Six years later Muybridge proved that in fact all four feet of a trotting horse simultaneously get off the ground. He did so by capturing a horse’s movement in a sequence of photographs taken with a set of one dozen cameras triggered by the horse’s feet.

Muybridge invented the zoopraxiscope, which projects sequential images on disks in rapid succession, in 1879. The zoopraxiscope is considered to be one of the earliest motion picture devices. Muybridge perfected his technology for sequential photographs and published his photographs of athletes, children, himself, and animals. His books, Animals in Motion (1899) and The Human Figures in Motion (1901), are still used by many artists, such as animators, cartoonists, illustrators, and painters, as valuable references. Muybridge, who had a colorful career and bitter personal life, is certainly a pioneer of mocap and motion pictures (Figure 1.1).

Born in France, in the same year as Muybridge, was Etienne-Jules Marey. Marey was a physiologist and the inventor of a portable sphygmograph, an instrument that records the pulse and blood pressure graphically. Modified versions of his instrument are still used today.

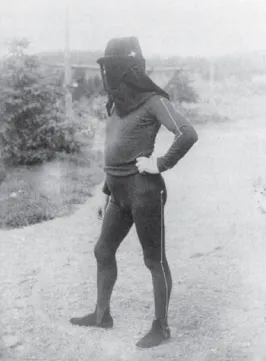

In 1882 Marey met Muybridge in Paris and in the following year, inspired by Muybridge’s work, he invented the chronophotographic gun to record animal locomotion but quickly abandoned it. In the same year he invented a chronophotographic fixed-plate camera with a timed shutter that allowed him to expose multiple images (sequential images of a movement) on a plate. The camera initially captured images on glass plates but later he replaced glass plates with paper film, introducing the use of film strips into motion picture. The photographs of Marey’s subject wearing his mocap suit show a striking resemblance to skeletal mocap data (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 1.1 Mahomet Running, Eadweard Muybridge, 1879

Marey’s research subjects included cardiology, experimental physiology, instruments in physiology, and locomotion of humans, animals, birds, and insects. To capture motion, Marey used one camera while Muybridge used multiple cameras. Both men died in 1904, leaving their legacies in arts and sciences.

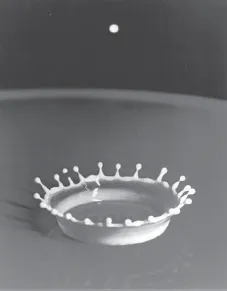

In the year after Muybridge and Marey passed away Harold Edgerton was born in Nebraska. Edgerton developed his photographic skills in the early 1920s while he was a student at University of Nebraska. In 1926 while working on his master’s degree in electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), he realized that he could observe the rotating part of a motor as if the motor were turned off by matching the frequency of the strobe’s flashes to the speed of the motor’s rotation. In 1931 Edgerton developed the stroboscope to freeze fast moving objects and capture them on film. Edgerton became a pioneer in high-speed photography (Figures 1.4 and 1.5).

Edgerton designed the first successful underwater camera in 1937 and made many trips aboard the research vessel Calypso with French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. He designed and built deep sea electronic flash equipment in 1954. Edgerton ended his long career as an educator and researcher at MIT when he passed away in 1990.

Figure 1.2 Etienne-Jules Marey’s mocap suit, 1884

Figure 1.3 Motion photographed by Etienne-Jules Marey, 1886

1.2.2 Rotoscoping

Max Fleischer, born in Vienna in 1883, moved to the U.S. with his family in 1887. When he was an art editor for Popular Science Monthly, he came up with an idea for producing animation by tracing live action film frame by frame. In 1915 Fleischer filmed his brother, David, in a clown costume and they spent almost a year making their first animation using rotoscope. Fleischer obtained a patent for rotoscope in 1917. World War I ended in 1918 and in the following year he produced the first animation in the “Out of the Inkwell” series and he also established Out of the Inkwell, Inc., which was later renamed as Fleischer Studio. In the “Out of the Inkwell” series, animation and live action were cleverly mixed and Fleischer himself interacted with the animation characters, Koko the Clown and Fitz the dog. In 1924, 4 years before Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” Fleischer produced the first animation with a synchronized soundtrack. Fleischer Studio animated characters from the comics, such as Popeye the Sailor and Superman. Betty Boop first appeared in Fleischer’s animation and later became a comic strip character. Fleischer’s early 30s animations were filled with sexual humor, ethnic jokes, and gags. When the Hays Production Code (censorship) laws became effective in 1934 it affected Fleischer Studio more than other studios. As the result, Betty Boop lost her garters and sex appeal.

Figure 1.4 Milk-Drop Coronet, Harold Edgerton, 1957

Figure 1.5 Shooting the Apple, Harold Edgerton, 1964

In 1937, after almost 4 years of production, Walt Disney (1901–1966) presented the first feature length animation, “Snow White and Seven Dwarfs.” “Snow White” was enormously successful. Paramount, the distributor of Fleischer’s animations, pressured Max and David Fleischer to produce feature length animations. They borrowed money from Paramount and produced two features, “Gulliver’s Travels...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: An Overview and History of Motion Capture

- Chapter 2: Preproduction

- Chapter 3: Pipeline

- Chapter 4: Cleaning and Editing Data

- Chapter 5: Skeletal Editing

- Chapter 6: Data Application — Intro Level: Props

- Chapter 7: Data Application — Intermediate Level: Decomposing and Composing Motions

- Chapter 8: Data Application — Advanced Level: Integrating Data with Character Rigs

- Chapter 9: Hand Motion Capture

- Chapter 10: Facial Motion Capture

- Chapter 11: Puppetry Capture

- Chapter 12: MoCap Data and Math

- Bibliography

- Appendix A: Shot List for Juggling Cow

- Appendix B: Sample Mocap Production Pipeline and Data Flow Chart

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access MoCap for Artists by Midori Kitagawa,Brian Windsor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.