- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environment and Children

About this book

How does the built environment affect children - their health, their behaviour, education and development? To support them, what do we need to consider and what do we need to do? Can our surroundings foster environmental and social awareness and responsibility?

Based on Christopher Day's experiences designing schools and early childhood centres in the United States and Britain, this groundbreaking book sets out to answer these questions and to offer solutions.

Children all too often find themselves living in alien surroundings designed with the needs of adults in mind, cut off not just from the natural environment but also childhood itself. Society's reaction - to cocoon children from the outside world or to resort to drugs to control behaviour - fails to address the fundamental causes of problems which lie in the environment not the children themselves.

One of the world's leading thinkers on the impact of buildings on people, Christopher Day's insights offer new light on one of the most important issues for today's society.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Environment for Children

Chapter 1

Design by Adults: Experience by Children

Environment and Child Development

Does environment affect child development? Does it influence what children learn, the values they acquire, and the path they will choose through adult life? Can childhood experiences inculcate environmental responsibility?

Everybody knows children need love. This affects everything. It’s critical for healthy psychological, social and bodily development – even influencing brain and nerves.1 In fact, without love, children develop brains up to 30 per cent smaller than those who grow up enveloped in it.2 But this is human, social environment. What about physical environment? This also influences brain development. From environmental experiences, the brain learns how it ‘needs’ to develop.3 What other developmental, educational and motivational influences do buildings and places have? Do they affect children’s – and subsequently, adults’ – health? Their physical, mental and moral development? Their social and environmental awareness?

If so, this places great responsibilities on everyone who designs, alters and administers places. It also raises questions. How should places for children be? Will adult design criteria produce appropriate environments for children? If sunbathing isn’t healthy for babies, what else do we need to look at in different ways?

Places as Exploratoria

Children and adults view the world differently.4 Buildings are designed by adults. But many, perhaps most, are used by children. When adults design buildings, practicality, energy-conservation, aesthetics and economy have major shaping influences. These are undeniably important – but have nothing to do with children’s experience.

Adult experience centres on how we use places; we know what they are for. For children, it’s more about what places ‘say’, how they meet and experience them. To them, the world is still fresh – one big sensory exploratorium. Hence railings and walls aren’t for excluding trespassers, but for rattling sticks or bouncing balls. Paula Lillard distinguishes these approaches: ‘children use the environment to improve themselves; adults use themselves to improve the environment. Children work for the sake of process; adults work to achieve an end result’.5 This means places – for adults – are for pre-defined purposes; but to children, they offer opportunities for things to do. This is a critical distinction.

Adults live (mostly) in a world of material facts – ‘known’ and unchanging. For children, the ‘real’ world is often servant to an imaginary world. Even single rooms, gardens or behind-the-shed forgotten places can be whole palettes of mood, whole geographies of mountains and jungles, harbours and shops – places to live out fantasy through action.

Walls are for walking along

Experience and Learning

How do children progress from a fantasy-shaped world to a fact-based one? How do they learn? Piaget considered that knowledge doesn’t develop as a linear progression, but as a relationship-network, dynamically interweaving connected elements. Perception, action, interaction with others and reflection develop, modify and consolidate it.6 Abstract knowledge doesn’t last. Cerebral knowledge unsupported by experience is unsustainable. Much that children learn intellectually, they compartmentalize as nothing to do with life. Not surprisingly, everybody understands things more quickly, more deeply, more multifacetedly and more meaningfully by experiencing them. In fact, until children are six years old, they only learn through experience – by doing – never through commands.7 They discover, understand and appreciate the world around them by active investigation.8 This ‘intuitive’ learning is whole-body and multisensory.9 As child psychologist Anita Olds observes, children ‘live continuously in the here and now, feasting upon nuances of color, light, sound, odor, touch, texture, volume, movement, form and rhythm around them’.10 (This persists into adolescence; how many teenagers do homework before the last minute?)

Innately compelled to learn about the world, children seek out concrete experiences. If these hold together – such as kitchens smelling, sounding, feeling and looking cosy – they can recognize connections and build a mental ‘whole’ from experiential ‘parts’. Contradictory experiences – such as luxuriously soft, bouncy furniture in ‘formal-behaviour-only’ rooms, or ‘leather’ smelling of PVC, are confusing. Confusion reduces confidence. Educationally, as plastic things can look very different but feel identical to touch, they imply knowledge from different senses have no meaningful relationship. Fragmentary, non-related knowledge weakens interest, so is thought to contribute to low attention span.11 In this age, plastic is barely avoidable. So, unfortunately is attention-deficiency. Sensory inconsistency is, of course, only one contributor amongst many probable causes.

Whereas adults already ‘understand’ things, children are still exploring the relationships between sensory messages. This makes them naturally creative. Sense-rich environments, by providing experience-experiments and imagination-opportunities of which we adults can’t conceive, further creativity development.12 In design, exuberant decoration can appeal to our sense of richness, but does it overburden children by excess? Does the decoration reinforce or confuse? Conversely, purely visual minimalism has a refined clarity and calm that can feed the soul. For adults, it can be an appealing aesthetic. But, if it doesn’t feed the senses, can it nourish children? Sterile buildings are actively harmful. These say soul-state doesn’t matter. They deserve no place near children.

Experience of Place

Children and adults also experience places differently. Their mood-world is more differentiated than ours. We easily categorize rooms as single-mood places: living room, bedroom, kitchen, classroom, gymnasium … For children, one room can comprise five distinct places: four corners and a centre.

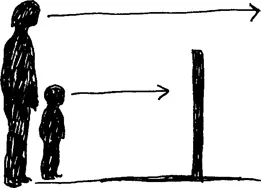

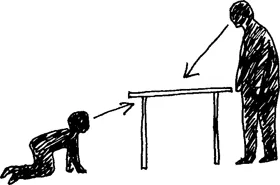

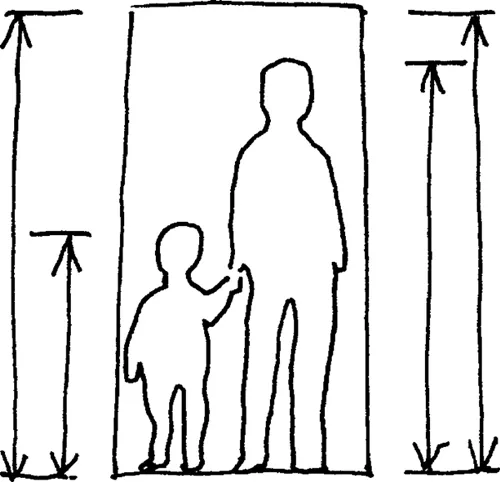

As lower eye-level shrinks spatial boundaries, children’s space differs from that of adults. Smaller relative scale, reach and range make places (small, when revisited as an adult) feel huge. Their spatial consciousness is also different. Adults navigate within a Cartesian spatial grid. This organizes our spatial experience, and lets us think causally. Small children interact with space more through life-energy than prethought-out rational intention. In mid-childhood, their actions are mostly led by emotions. Only at the threshold of adulthood can they fully steer their life, and respond to space, through thinking.

View above table

View above table

Different Thinking: Different Learning: Different Needs

Much conventional education focuses on intellectual development. But what about emotional development? Psychology often treats thought and feeling as opposites. Although, like Freud, Piaget separated their development, he recognized that whole understanding depends on a balance between emotional and intellectual comprehension.13 Vygotskij observed that significance – hence meaning – is inseparable from feelings. He considered consciousness to be a dialogue of diverse mental forms, with feeling and thinking inextricably interlinked, but thought to be only a monologue to the world.14

Proportional scales

Is there only one type of intelligence? Howard Gardner postulates seven: logical/ mathematical, linguistic, musical, spatial, bodily/kinaesthetic, self-knowledge and social.15 Different aspects of environment feed these different intelligences. Energy-conscious design, for instance, demonstrates causality. Spatial and kinaesthetic sensations are inseparable from experience of place. Architecture can both feed sense-of-self and help build society. Form-and space-language, harmony, melody, tempo and rhythm are its means.

These many intelligences raise questions about what it means to be human. Machines excel at logical intelligence. They’ll soon be better at this than humans. (They’re already better at rememberi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Table Of Contents

- Environment and Children

- Environment and Children

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Environment for Children

- Design by Adults: Experience by Children

- Childhood: a Journey

- Developmental Needs: Challenge and Certainty

- Part II: Health: Physical, Developmental and Social

- Social Relationships and Place

- Issues of Health

- Part III: Environment as an educational aid

- Our Senses: Meeting the World

- Light and Darkness: Age and Situation

- Colour and Children

- Space: Shape and Quality

- Part IV: Places for children

- What Places Teach: Silent Lessons

- Welcoming Arrival

- Part V: Environment for Children

- Outdoor Places

- Environment for the Developing Child

- Part VI: Sustainability lessons from surroundings

- Learning to care for the Environment

- Making Nature's Cycles Visible

- Living with the Elements

- Levels of Life

- Learning Sustainability through Daily Experience

- Sustainable Schools

- Part VII: Environment to serve and inspire

- From Ends to Means

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Environment and Children by Christopher Day,Anita Midbjer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.