![]()

1

Invisible technique

Learning the ropes

There have been a number of boy-wonders and young prodigies in the history of film making but the most spectacular debut was when 25-year-old Orson Welles was summoned to RKO in 1939 to make his first movie. He had no experience of film making and Miriam Geiger, a researcher at RKO, explained camera angles to the young Welles by cutting out frame holes in pieces of paper and pasting over a selection of shot sizes taken from a reel of film She added a short text description to remind Welles of the building blocks of film making.

Welles remembers that in the second week of shooting ‘Citizen Kane',

an awful moment came when I didn't understand [screen] directions. That was because I had learnt how to make movies by running ‘Stagecoach’ [dir. John Ford, 1939] every night for a month. Because if you look at ‘Stagecoach’ you will see that the Indians attack [the stagecoach] left to right and then they attack right to left and so on. In other words, there is no direction followed –every rule is broken in the picture, and I sat and watched it forty five times, and so of course when I was suddenly told in an over-shoulder shot that I had to look camera left instead of camera right, I said no because I was standing here – that argument you know. And so we closed the picture down about two in the afternoon and went back to my house and Toland [the film's cinematographer] showed me how that worked, and I said ‘God there is a lot of stuff here I don't know', and he said ‘There's nothing I can't teach you in three hours'.

(The Complete Citizen Kane', BBC TV)

Greg Toland was right. You can understand the visual grammar of film making in an afternoon. You can, in the same time, also learn the position of every letter of the alphabet in the ‘qwerty’ layout of a word processor keyboard. Knowing where each letter of the alphabet is positioned will not make you into a writer. How words are combined to make meaningful sentences will take longer. Creating vivid and memorable prose equal to the greatest novelists may never be achieved. If Welles was ignorant of film technique when he began shooting ‘Citizen Kane', he must have been a prodigious high-speed trainee because, in the opinion of French film director Francois Truffaut, ‘Citizen Kane’ inspired more would-be directors than any other film.

Many newcomers to film and TV programme making often assume that as content and subject differs widely between programmes they must employ specific individual methods in their production. Film and television programmes are seen as one-off, custom-built entities. They may be surprised to find that there are significant links in technique, for example, between a 1930s musical, a 1940s crime film and a contemporary televised football match. The majority of productions (but not all – the exceptions will be discussed in the next chapter), share a common visual grammar. Like spoken language, this set of conventions was not originated by a group of academics laying down the law. The visual grammar evolved over time, through practical problem solving on a set, at a location or in an editing booth. This body of visual recipes is sometimes called invisible technique or continuity editing, and it evolved at the very beginning of film making.

It is important to understand the role composition plays in sustaining ‘invisible technique', but it is equally important to remember that this is only one type of visual language. There are alternatives to this system, although ‘invisible technique’ is the predominant code used in nearly every type of film and television production. Its use is so widespread that many people in the industry believe that it is the only valid set of conventions. They suspect that anyone using alternative techniques is either ignorant of the standard conventions or is simply incompetent. To some extent they are correct if the production is aimed at a mass audience who usually anticipate and intuitively understand certain visual forms learnt over a lifetime of watching popular story telling on film and television. Unfamiliar codes of film making may confuse and ‘switch-off’ a mass audience.

A moving photograph

‘Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory’ is considered by many film historians to be the world's first moving picture. It was made by the Lumière brothers and, on 22 March 1895 in Paris, it was possibly the first film to be projected to an audience. Nine months later, on 28 December 1895, a paying audience watched a number of films made by the brothers including ‘Arrival of a Train at a Station', ‘Baby's Lunch’ and ‘The Sprinkler Sprinkled'.

These ‘films’ were single-shot, ‘actualities’ or documentary views with the camera framing a fixed viewpoint. They were considered as moving photographs and were unlike later developments in film making in both how they were made – a single uncut shot – and in how they were understood by their audience. Audiences were familiar with slide shows, some with mechanical moving images accompanied by a commentary and/or music. It has been suggested that early film was seen by audiences as a continuation of slide presentation and other serial projection of images. They were like the series of pictures, the Rakes Progress, painted by William Hogarth in 1735. Each picture had individual interest but were linked by a common theme. The first moving pictures were discontinuous, animated photographs and in themselves did not form a continuous narrative. The images were not self-sufficient in telling a story and were possibly not conceived as telling a story by their producers or audience. The concept of film narrative and the required technique to create a convincing set of consecutive images had to be learnt by film makers and cinemagoers.

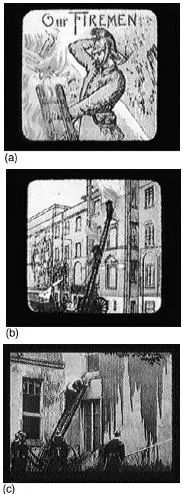

Figure 1.1 (a) The title slide of a series of Victorian coloured illustrations of scenes of a fire. Another drawing (b) depicts firemen rescuing the trapped inhabitants of the building on fire. As one slide followed another, often accompanied by an explanatory spoken commentary, different events could be shown out of sequence and still be understood by the audience. A shot from an early silent film (c) of the same subject. The shots in the film followed the conventions of the slide show and made little attempt to persuade the audience they were watching a continuous event in real time. The difference was that film provided a series of moving illustrations

In a rudimentary form, basic film technology (except the recording of film sound) was invented by 1896, but the idea that film's primary purpose was to convince and persuade an audience they were watching a continuous event had to be recognized. During the 1890s, multi-shot views were shown, sometimes compiled by the exhibitor from different suppliers, and sometimes by the producers of film, without the concept that film could tell a story.

It has been suggested that Mèliès, in the 1890s, recognized the potential of film's ability to manipulate time and space when his camera jammed whilst shooting a bus leaving a tunnel. After clearing the camera jam he continued filming with the camera framed on exactly the same view and then found, when the film was developed, that the bus had miraculously turned from a bus into a hearse. This may be an apocryphal story, but it demonstrates the potential of film technique that Mèliès in a pioneering way was able to develop. He continued to shoot separate scenes containing no shot change and simply conceived the camera as the static eye of a privileged theatre spectator witnessing a series of magical illusions.

The claim that audiences for this primitive cinema saw the presentation differently from later cinemagoers is based on the conjecture that they were being shown views rather than being told a story. Film academic Tom Gunning proposed that cinema development split between story telling, which went on to dominate commercial cinema, and the cinema of attraction, which went underground and turned into avant-ga rde film Primitive cinema in this sense was a series of visual displays providing spectator pleasure.

Continuity cinema

With magic lantern shows such as ‘Fire', a rudimentary story was told, expanded by an accompanying commentary, of the start of a house on fire, raising the alarm at the fire station, the firemen journey to the fire, the fire raging in the interior, firemen with hoses and then climbing a ladder, followed by a rescue. Although there was a need for space relationships to be clear (e.g., interior fire station was distinct from interior burning house), there was really no need for time to follow a linear path.

There could be overlapping of time because as one slide followed another different events could be shown out of sequence and still be understood by the audience. Theatrical presentations such as Mèliès films are a series of scenes that the audience observe from their individual single viewpoint. Film storytelling gradually evolved a technique that allowed multiple perspectives or viewpoints without disrupting the audience's involvement with the story.

Film added a time dimension, and a major problem for film makers was to establish linear continuity. They discovered that action could be made to seem continuous from shot to shot. Instead of each shot being seen as a different and distinct view, similar to turning the pages of a photo album, film makers learnt how to join the views together into a seamless flow of images.

In early film, action was played out to its end before moving to another piece of action. Unlike the single-shot actuality pioneering films, the director of ‘The Great Train Robbery’ (1903), Edwin S. Porter, cut away from action before it was concluded. Although he did not intercut during a scene this effectively was the invention of the shot.

The shot

The shot replaced the scene to become the unit of storytelling. In the period from the Lumière brothers’ first public projection of film to the outbreak of war in 1914, film making moved from a series of tableaux scenes echoing Victorian slide shows and theatre presentations, to a unique method of narrative presentation. Theatre relies on scenes, staging action, movement, lighting and text to make the required dramatic point. Film invented the concept of multi-positioned viewpoints. These innovations occurred as the result of practical problem-solving rather than abstract theorizing.

A photograph does not need another photograph to explain it; it is self-contained. A film shot is a partial explanation – a piece of a jigsaw puzzle. The innovation in film making was to tell a story in individual images (shots) that did not disrupt the audience's attention by the methods used to produce the pictures. It was a coherent set of visual conventions and techniques that aimed to be invisible to the audience. The first film makers had to experiment and invent the grammar of editing, shot-size and the variety of camera movements that are now standard. The ability to find ways of shooting subjects and then editing the shots together without distracting the audience was learnt over a number of years.

The creation of 'invisible' technique

The ability to record an event on film was achieved in the latter part of the nineteenth century. During the following years, there was the transition from the practice of running the camera continuously to record an event, to the stop/start technique of separate shots where the camera was repositioned between each shot in order to film new material. The genesis of film narrative was established.

There was a moment of discovery when someone first had the idea of movi...